One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power (11 page)

Read One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power Online

Authors: Douglas V. Smith

NOTES

Almost all information in this essay was extracted from Edward S. Miller,

War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897â1945

(Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991). The book cites documentary sources such as war plans and related correspondence found mainly in the U.S. National Archives, the Naval Operational Archives Branch, and the Naval War College. Information on flying boats is found under “Flying Boats” in the book's index, under these subcategories: bases for; in blockade; characteristics and numbers; civilian; flights, notable; in phase II; as scouts; as striking force; in WWII; and under “Seaplane tenders.”

Â

1

.

Â

In the “color” plans of the Joint Army-Navy Board Japan was designated “Orange” and the United States “Blue.” Until 1940 the plan envisioned a war without allies on either side and a war theater limited to the Pacific north of the equator.

John E. Jackson

FIGHTING WORDS

W

henever fliers gather around a frosted mug there is an immediate and inevitable separation into distinct categories for bragging rights about which group is best in the air: fixed-wing versus rotary wing; fighter jocks versus bomber aces, Maritime Patrol practitioners versus multi-engine bomb and cargo haulers; and in recent years, manned versus unmanned aircraft! But a century ago, the biggest division would have been between lighter-than-air (LTA) proponents and heavier-than-air (HTA) advocates. And as strange as it may now seem through the lens of history, in the early years of aviation the smart money was riding on airships as the platforms that would rule the skies for long-range and heavy-lift missions.

In 1911, at the same time Eugene Ely was barely able to keep his wood-and-wire-powered “box-kite” in the air for periods measured in minutes, the German Airship Transport Company, Ltd., established the world's first airline. Its airship

Deutschland

completed a powered flight of two hours and thirty minutes, with thirty-two people on board.

1

A Schutte-Lanz airship of the period was 420 feet long, 59 feet in diameter, with two engines producing 540 horsepower that could push the airship through the sky at over thirty-eight miles per hour.

2

Between 1911 and the opening of World War I in 1914, commercial airships in Europe carried more than 34,000 passengers, flying more than 100,000 miles.

3

There were plenty of growing pains for these monsters-in-the-sky, and crashes were frequent (if not fatal), but their potential was clearly evident. Military observers were quick to see the possibilities for airships to meet a wide range of military missions.

A WORD ABOUT TERMINOLOGY

Perhaps the arcane terminology used in discussing lighter-than-air craft has contributed to the mystique and misunderstanding of these “ships in the sky”. For purposes of this chapter, let's just say the following: Any steerable flying machine that relies on the buoyant lift from a gas that is lighter than the air in which it flies is an “airship.” If it has an internal framework to maintain its aerodynamic shape, it is a “rigid airship.” If it is a rigid airship built by the Germans in the 1920sâ1930s, it is a “Zeppelin.” And if it uses only internal gas pressure to maintain its shape, it is a “blimp.” The term “dirigible” means “steer-able,” and has nothing to do with rigid or non-rigid status, though the term is often erroneously used to describe rigid airships. Finally, manned balloons, lifted by gas or by hot air, cannot be controlled directionally, and thus had little practical application beyond flight training for airship crewmen.

IN THE BEGINNING

Even with only a cursory look, the attraction of airships for naval operations becomes readily apparent. In the decades of the 1920s and 1930s, blimps, and their larger and more capable rigid airship “cousins,” offered the ability to carry heavy loads for long distances. They could virtually hover for days in one location, or travel at low speeds to match the progress of surface ships and merchant convoys. They could then sprint at close to one hundred miles per hour to reposition themselves to inspect a new target or to escape a gathering storm. They held great promise as the ultimate airborne observation platforms, capable of covering thousands of miles of ocean in a single mission. Realizing these potential capabilities, however, demanded state-of-the-art aeronautical engineering, a host of technological breakthroughs, and superb airmanship. The history of Navy LTA flight is filled with triumphs and tragedies as men of courage sought to deliver on the promises made by LTA advocates around the world.

The U.S. Navy's first blimp was the DN-1, delivered to Pensacola, Florida, in the spring of 1917. It was followed by sixteen B-type non-rigid airships, which were little more than an airplane fuselage suspended under an 84,000-cubic-foot helium-filled envelope. The mission was to patrol the East Coast of the United States in search of German submarines. Refinement in airframes and engines continued over the ensuing decades, and Navy blimps grew in size and complexity, ultimately serving with great success during World War II, and into the Cold War.

But the real technological leap forward came with the design and construction of rigid airships, such as the German Zeppelins that had proved formidable scouts and bombers in World War I.

RIGID AIRSHIPS

The 1920 naval appropriations bill authorized the expenditure of $4 million to obtain two rigid airships. The visionary often called the “architect of Naval Aviation,” Admiral William A. Moffett, wrote to the Chief of Naval Operations shortly after becoming head of the Bureau of Aeronautics: “In the rigid airship we have a scout, capable of patrolling the Pacific in the service of information for our fleet. . . . The use and development of rigid airships is a naval necessity.”

4

The first American-built ship would be designated ZR-1 and construction began in a newly erected hangar in Lakehurst, New Jersey, in April 1922. Anxious to get into the air as soon as possible with a blue-and-gold behemoth, the U.S. Navy simultaneously sought to purchase a flight-ready rigid airship from the British builder Short Brothers. Upon the planned transfer to the United States, the British R-38 airship would have been re-designated as ZR-2, but fundamental design flaws led to catastrophic failure of the ship over the city of Hull, England, in 1921, and the death of forty-four crewmen, including sixteen Americans who were aboard preparing to accept the ship.

Attention then turned to the construction of the huge rigid-framed ZR-1, the USS

Shenandoah

, which was closely modeled after a German Zeppelin that crashed in England during World War I. First flown in September 1923, the ZR-1 measured 680 feet in length and 79 feet in diameter. She was lifted by 2,100,000 cubic feet of helium, had a top speed of sixty knots and a crew of forty-three. It truly was a ship in the sky, which Navy leaders envisioned as the ideal long-range ocean reconnaissance platform, with extraordinary lift, range, and endurance. It proved to be an inferior design, however, and after two years of flight-testing (and public relations flights) it encountered a massive thunderstorm near Ava, Ohio. It broke up in flight and crashed in September 1925 with the loss of fourteen lives. Shaken by the two losses, the Navy designers redoubled their efforts.

Over the course of the decade that followed, millions of dollars and scores of lives would be consumed in the quest to develop the technology and operational doctrine necessary to achieve the ambitious potential promised by rigid airships. The designers sought to arrive at an elusive formula: a ship large enough to carry the aircrew, food, fuel, and equipment to do the job, yet light enough to be lifted aloft by its helium-filled gas bags. The spiderweb of duralumin girders that formed the hull had to be light enough to fly, yet strong enough to handle the incredible aerodynamic loads and stresses experienced by what was fundamentally a fragile 700-foot-long cylinder suspended in mid-air. Looking back across nine decades of history, it can be argued that it was simply beyond the capabilities of the engineers of the early twentieth century to divine a workable formula. But the potential benefits of LTA flight were so great that courageous pioneers continued to risk reputations, careers,

and even lives in their pursuit. Their quest culminated in two of the most remarkable flying machines ever to take to the sky under the command of Navy aviators.

FLEET SCOUTS AND FLYING AIRCRAFT CARRIERS

In the 1920s, American statesmen and military experts viewed the growing power of the Empire of Japan with concern, and recognized that the small and ill-equipped U.S. fleet was wholly inadequate to patrol the vast reaches of the Pacific Ocean. In 1919, Captain (later Fleet Admiral) Ernest J. King reported to the Navy's General Board: “I don't see how the long distance reconnaissance is going to be carried out without using dirigibles.”

5

After World War I, U.S. Naval Forces-Europe Commander Admiral William S. Sims stated: “I am thoroughly convinced by my observance of the naval lessons of this war that in the future rigid airships will be part of the fleet of every first-rate naval power.”

6

The Navy had learned in the most painful way possible that neither the captured German design of ZR-1 nor the British design of ZR-2 resulted in a successful naval rigid airship. (In 1924 the Navy received a German-built Zeppelin airship, designated ZR-3 and named the USS

Los Angeles

, as a war reparations payment, but by treaty agreement it was to be used solely for “civil purposes.” It was a variant of a commercial Zeppelin design that had little application for the intended long-range scouting mission). In 1928 the Navy called for proposals to build a rigid-frame fleet reconnaissance airship, capable of launching and recovering fixed-wing scouting aircraft while in flight. Three companies submitted proposals, and the contract to build two airships (ZRS-4 and -5) was awarded in October 1928 to the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation, a partnership created in 1924 to share rigid airship technology. Executing the contract was another matter.

The construction of the ZRS-4, the Akron, stands as one of the most remarkable performances in the history of American industry. In the two years, eleven months and 2 days between the moment the ink dried on the airship contracts in Washington and when the Akron was cast off from her mooring mast at Akron, Ohio, not only did a hangar to house the erection work have to be built, but a corps of technicians and production personnel had to be developed around a cadre of German engineers; hundreds of workers had to be trained to an art almost unknown in America; and thousands of drawings had to be translated into patterns and jigs for what was to be the largest airship in the world. In order to build these two airships Goodyear was obliged, in one leap, to create an industrial plant of a magnitude which the airplane industry required almost a quarter century to develop.

7

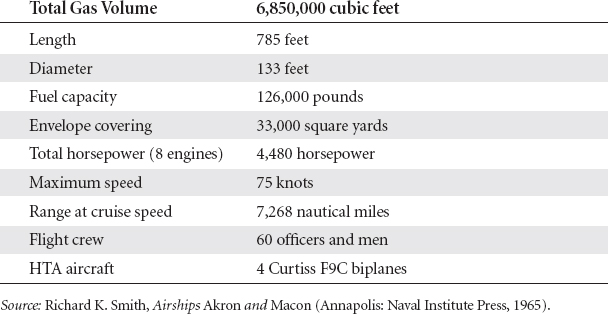

The statistics of the

Akron

and her sister ship

Macon

were remarkable:

Total Gas Volume | 6,850,000 cubic feet |

Length | 785 feet |

Diameter | 133 feet |

Fuel capacity | 126,000 pounds |

Envelope covering | 33,000 square yards |

Total horsepower (8 engines) | 4,480 horsepower |

Maximum speed | 75 knots |

Range at cruise speed | 7,268 nautical miles |

Flight crew | 60 officers and men |

HTA aircraft | 4 Curtiss F9C biplanes |

Source: |

On 8 August 1931, First Lady Lou Hoover christened the USS

Akron

, named for the city in which it was built, then considered the “LTA Capital of the World.” The Navy now had the prototype of the fleet airship it wanted, but rather than being subjected to the type of slow and deliberate flight-testing one would expect for a totally new aircraft design,

Akron

was pushed to demonstrate her value to skeptical observers both inside the Navy and in the media. In fleet exercises, during a transcontinental flight to San Diego and Sunnyvale, California, and through numerous operations where her scouting aircraft were launched and recovered, the

Akron

demonstrated that she had the potential to provide the fleet with unprecedented intelligence-gathering capability.