One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power (3 page)

Read One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power Online

Authors: Douglas V. Smith

NOTES

Â

1

.

Â

John Gillespie Magee Jr. poem “High Flight.”

Â

2

.

Â

This was a statement made frequently by instructor pilots while I was undergoing pilot training in Meridian, Mississippi, and Beeville, Texas. It relates to less than two percent of humans having ever landed on an aircraft carrier. At the time, few if any of us had any comprehension of or appreciation for the danger inherent in our chosen profession. Reminders such as this were, in retrospect, intended to boost our confidence psychologically beyond rational limitsâan absolute necessity for all Navy pilots.

The Experimental Era: U.S. Navy Aviation before 1916

Stephen K. Stein

INTRODUCTION

O

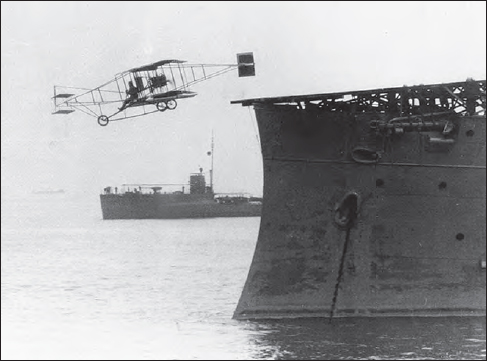

n 14 November 1910, Eugene Ely flew a fifty-horsepower Curtiss pusher biplane off an 82-foot platform hastily constructed on the cruiser

Birmingham

. The plane cleared the ship, but then dropped rapidly. Its propeller touched the water, shattering its tips, as Ely, hampered by a bulky lifejacket and blinded as water sprayed across his goggles, struggled to gain altitude. Successful, he flew his damaged plane toward the Norfolk Navy Yard. He landed his damaged aircraft at Willoughby Spit five minutes later after a two-mile flight.

The person who arranged this record-making flight, the first take-off of an airplane from a ship, was Navy Captain Washington Irving Chambers. The bureaucratic obstacles and other challenges Chambers overcame to arrange this simple demonstration exemplify the problems he and other aviation enthusiasts faced promoting aviation and building a Navy aviation program in the years before the United States entered World War I. From the first glimmerings of interest in Navy aviation in 1898 to 1916, when the United States began to prepare for major war, aviation advocates faced an uphill struggle that tested their endurance, technical skills, and their acumen for political and bureaucratic maneuvering. In this experimental era, aviation proponents had to prove aircraft both safe and of military utility before they could integrate them into existing military organizations. In the United States, they faced doubting superior officers, a skeptical and penurious Congress, rival inventors, and a slew of bureaucratic impediments and technological factors that singly and in combination hindered innovation and the dissemination of aircraft throughout the Army and Navy.

THE BEGINNINGS OF MILITARY AVIATION

Practical aviation began more than a century earlier with the balloon flights of the Montgolfier brothers who first ascended in one of their creations in 1783. A decade later, France's Revolutionary Army deployed observation balloons at several battles. Napoleon, though, found little use for them and military ballooning disappeared over the next generation. During the American Civil War, civilian aeronauts, particularly John Wise, John La Mountain, and Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, operated balloons for the Union Army. These included balloon flights off the collier

George Washington Parke Curtis

and transport

Fanny

, which marked the birth of Navy aviation. In the first of these, in August 1861, La Mountain ascended from the

George Washington Parke Curtis

, then anchored in off Sewell's Point in Hampton Roads, and sketched Confederate fortifications and artillery positions while hoping to locate the CSS

Virginia

.

1

Historian Craig Symonds jokes that this was the first American aircraft carrier.

Despite some successes, the Army abandoned balloon operations before the war's end. Yet when U.S. troops landed in Cuba in 1898, they brought an observation balloon and its crew helped direct the American advance until Spanish rifle fire brought it down. These balloon flights demonstrated the potential for aviation to transform warfare, but balloons proved too slow, vulnerable, and slow to deploy to inaugurate that transformation. Militaries needed more effective aerial units and, in the last years of the nineteenth century, funded several pioneers exploring heavier-than-air and powered flight.

Researchers around the world struggled to unravel the mysteries of flight as the nineteenth century neared its end; the more prominent included machinegun inventor Hiram Maxim in Great Britain, Clement Ader in France, and Otto Lilienthal, the “Flying Prussian.” Later revered as the father of hang gliding, Lilienthal made more than two thousand flights in a variety of gliders before dying in a crash in August 1896. Maxim lost control of his business, and with it support for aviation research, while Ader's bat-shaped

Avion III

stubbornly refused to fly in its 1898 trials. Others proved equally unsuccessful. While aeronautic research continued in Europe, attention turned to airships, which Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin in Germany and Alberto Santos-Dumont, then living in Paris, regularly demonstrated after 1900.

Beginning in 1887, Samuel Pierpont Langley, the Director of the Smithsonian Institution, built successively larger gliders and steam-powered model aircraft, one of which flew for ninety seconds on 6 May 1896, traveling three thousand feet. Langley extended this to a mile in later tests and his continued success brought him to the attention of prominent individuals including Alexander Graham Bell; Charles Walcott, the Director of the Geological Survey; and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt who arranged a joint ArmyâNavy Board to examine recent

flight research on the eve of the Spanish-American War. This six-member board, chaired by Commander Charles H. Davis, the Naval Observatory's director, concluded that it would soon be possible to build a heavier-than-air craft capable of carrying a pilot and a small cargo. They recommended funding Langley's research and suggested that aircraft could soon be used for reconnaissance and spotting, carrying messages between military forces, and bombing enemy camps and fortifications. Unfortunately, the members of the Navy's Construction Board (the Chief of Naval Intelligence and the chiefs of the bureaus of Construction and Repair, Equipment, Ordnance, and Steam Engineering) declared aviation research premature and unsuited to the Navy.

2

Naval History and Heritage Command

The Army, though, found $50,000 for Langley who over the next five years built his full-sized aircraft. Dubbed the

Aerodrome

(due to Langley's poor command of Greek), it was powered by a fifty-two-horsepower gasoline engine built by his assistants Stephen Balzer and Charles Manly who would fly the craft. Scaled up from models without sufficient redesign and testing, the fragile

Aerodrome

lacked landing gear and had only a small rudder for control. Launched by a spring catapult from a houseboat on the Potomac River on 7 October 1903, the craft plunged into the river after a strut snagged the launch mechanism. Launched again two months later on

8 December, the

Aerodrome

's rear wings buckled after only a brief moment in the air. It crashed into the Potomac, though Manly again survived.

3

Langley's failures confirmed the doubts of skeptics, including Rear Admiral George W. Melville, one of the most respected engineers in the Navy. Two years earlier, Melville pronounced heavier-than-air flying machines “absurd” and condemned aviation research by noting that there was “no field where so much inventive seed has been sown with so little return as in the attempts of man to fly successfully through the air.”

4

Government funding for aviation met the same fate as Langley's

Aerodrome

, vanishing under a hail of criticism and condemnation. Langley, himself, died a few years later in 1906.

THE WRIGHT BROTHERS

While Langley's failures received full, and rather harsh, attention in the press, Orville and Wilbur Wright achieved the first powered, sustained, and controlled flight in relative obscurity on 17 December 1903, nine days after the second and final crash of Langley's

Aerodrome

. Through painstaking research, the Wrights corrected the errors of their predecessors and built on their successes, fusing the work of several designers. Unlike many of their predecessors, they recognized the importance of controlling flight in all three dimensions (pitch, roll, and yaw). They used glider data and wind tunnel tests to build a better airfoil and develop control mechanisms, and successfully integrated diverse technologies into a single airframe. As aviation historian Richard Hallion notes, they recognized the importance of “progressive flight research and flight testing” and followed “an incremental path from theoretical understanding through ground-based research methods” and then flight trials of a succession of models until they worked their way to piloted aircraft. After several successful flights, a wind gust smashed the

Flyer

. The Wrights returned home to Dayton, Ohio, with the wreckage and spent the next two years refining and improving their design. Their new 1905

Flyer

seated two people and was capable of long flights, such as Wilbur's twenty-four-mile, thirty-eight-minute flight on 5 October. Finding buyers for their plane proved difficult, though, and they soon focused on the military as the only likely purchaser of significant numbers of aircraft.

5

Despite their disappointment with Langley, several Army Signal Corps officers kept abreast of aviation developments. In 1907, Major George O. Squire toured Europe to study aviation developments.

6

That August, the Army created an Aeronautical Division within the Signal Corps. Prodded by civilian aviation enthusiasts, particularly the members of the Aero Club of America (formed in 1905 by members of the Automobile Club of America) and President Theodore Roosevelt, the division advertised the world's first specifications for a military aircraft. Of the twenty-four bidders, only the Wrights delivered a working airplane.

While Wilbur took one plane to France, where he astounded audiences, Orville flew their new

Military Flyer

for the Army in a succession of test flights at Fort Meyer, Virginia, in the summer of 1908. The several thousand witnesses included two Navy observers: Naval Constructor William McEntee and Lieutenant George W. Sweet, a radio expert who had developed an interest in aviation. Orville took several passengers aloft including Squire, but the demonstrations ended when a propeller blade shatteredâits fragments sliced through bracing wiresâand the plane plunged to the ground seriously injuring Orville and killing his passenger, Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, the first airplane fatality. A champion of aviation who had ascended in giant kites and contributed to the work of the Aerial Experiment Association, a group led by Alexander Graham Bell, Selfridge would be missed.

7

The crash delayed the remaining tests until the following summer when the Wrights again astounded observers with both their plane and their aeronautic acumen. Sweet, who had traded places with Selfridge the previous year, finally flew as a passenger on 9 November, becoming the first American Navy officer to fly. The Army accepted the

Military Flyer

into service that August, making it the world's first military Service with an airplane. Supported by Rear Admiral William S. Cowles, the Chief of the Bureau of Equipment, Sweet recommended that the Navy purchase airplanes. The Navy's senior leadership, though, dismissed the idea. Speaking for them, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Beekman Winthrop declared that airplanes had not “progressed sufficiently at this time for use in the Navy.”

8

France hosted the first international air show and flying competition later that summer. Twenty-five aircraft competed for prizes at the Reims Air Meet (22â29 August 1909), which showcased aeronautic progress. While American Glenn Curtiss won two trophies for speed in his

Reims Racer

, European aircraft and aviators dominated the other events. The Wrights, concerned about infringement on their patents, refused to participate, though several contestants flew Wright aircraft. The U.S. Navy's observer at the show, Commander Frederick L. Chapin, recommended deploying airplanes on battleships and building new ships with flight decks. The Navy dismissed his recommendations, as it had Sweet's, but Glenn Curtiss would prove difficult to ignore.

9

Curtiss, who set a world speed record riding one of his motorcycles in 1907, expanded his business into aircraft engines and then airplanes over the next few years. Flying airplanes of his own design, he quickly won several prizes including the $10,000 Bennett Prize for the fastest twenty-kilometer flight and the Prix de la Vitesse for averaging 46.63 mph over thirty kilometers at Reims. The following year, the flamboyant inventor flew one of his new planes 137 miles (with two stops to refuel) down the Hudson River from Albany to New York City to win a $10,000 prize offered by the

New York World

. Afterward he told reporters that airplanes would soon take off from ships and that warships were already vulnerable to

air attack. “The battles of the future,” he proclaimed, would “be fought in the air.” In July Curtiss flew over a battleship-sized target on Lake Keuka and dropped eight-inch lengths of lead pipe on it, striking it repeatedly. The stunt encouraged the

New York Times

to join the

World

in trumpeting the military possibilities of aviation.

10