One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power (2 page)

Read One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power Online

Authors: Douglas V. Smith

G

EORGE

H. W. B

USH

Â

Lieutenant, U.S. Navy Reserve

Â

T

he authors would all like to express our sincere thanks to President George Herbert Walker Bush, forty-first President of the United States, not only for providing the foreword for this book, but for his gallant service as a pilot wearing the Navy Wings of Gold in World War II in the Pacific. We thank President Bush as well for saluting all those who have worn or now wear the Wings of Gold, those who have kept and continue to keep them in the air, and those who, past and present, have kept the home fires burning while awaiting their return.

We would also like to thank Mr. Danny Pietrodangelo and his associate, Ms. Dale Harness, of Pietrodangelo Production Group in Tallahassee, Florida, for their excellent photo research and photo editing work for this project.

Dr. Al Nofi would like to add his thanks to Admiral James Hogg, USN (Ret.), and his shipmates from the CNO's Strategic Studies Group, 2001â2005; as well as the staff of the Naval War College Library and the Naval War College Archives; Editor Emeritus of the

Naval War College Review

, Frank Uhlig; and Dr. Thomas Hone, without whom his chapter and this entire book would not have been possible.

I add my thanks to all of these, but especially to Tom Hone, who helped envision this project.

Capt. John Jackson, SC USN (Ret.) would like to extend his thanks to Vice Admiral Charles E. Rosendahl, USN (Ret.), who commanded all Navy airships in World War II and was the commanding officer at Naval Air Station Lakehurst the night the German Zeppelin Hindenburg crashed. John's meeting and discussions with Vice Admiral Rosendahl provided fascinating details of the age of airships. John

also thanks his loving wife, Valerie, for her untiring support and encouragement of all that he does.

Tim Jackson and Stan Carpenter thank Mr. Nathaniel Patch at the National Archives and Records Administration for his assistance in locating many essential records relating to naval legislation and appropriations bills.

Dr. Norman Friedman above all wants to thank his wife, Rhea, for her warm support throughout this project. Dr. Friedman's acquaintance with the story of U.S. carrier design dates back to a NAVSEA project sponsored by Dr. Reuven Leopold, who was then senior civilian ship designer (and who had designed the

Tarawa

-class large-deck amphibious ships and the

Spruance

-class destroyers). Dr. Leopold wanted Dr. Friedman to use the NAVSEA preliminary design files to find out why the U.S. Navy preferred large to small carriers. Through Dr. Leopold he became acquainted with the Navy's preliminary designers, including Herbert S. Meier, who led the team that produced the preliminary design for the

Nimitz

-class carriers. “I hope I have done them justice. I also want particularly to thank Dr. Evelyn Cherpak, who is responsible for the archive of the Naval War College and to thank the staff of the U.S. National Archives and Records Agency, at both the downtown Washington, D.C., and College Park locations. I would also like to thank Dr. Thomas C. Hone of the Naval War College for many valuable insights developed during our two Joint projects for the Office of Net Assessment. I am grateful to Charles Haberlein, photo curator of the Naval History and Heritage Command, for help not only with photographs but also with much wider issues of ship development and employment.”

Hill Goodspeed gratefully acknowledges Captain Robert Rasmussen, USN (Ret.), and Dr. Robert R. Macon of the National Naval Aviation Museum for their longtime support of his work, and thanks those many naval aviators and aircrewmen who over the years have shared the experiences that have done so much to inspire his writing

Dr. Mike Pavelec singles out Dr. Evelyn Cherpak, Archivist of the Naval War College, for her great support of his archival research, and Hill Goodspeed, Historian of the Naval Air Museum in Pensacola, Florida, who is also a contributing author of this work, for his important help on research of all aspects of Navy aviation.

Finally, as editor of this book, I want to thank each of the authors who have shared their insights and scholarship by providing the chapters herein. Every one of them submitted their chapters on time or ahead of schedule, a rarity in the academic community. Experts all, they have made my job easy and enlightened me in the process.

My thanks go out to Dr. Evelyn Cherpak, echoing those above. She is a consummate professional and incredible resource for all scholars of U.S. Naval History. Likewise, I thank Ms. Alice Juda, Senior Reference Librarian and the strongest possible supporter of the scholarly research efforts of members of the Naval War College

faculty and student body. Mr. Dennis Zambrotta, library technician at the War College, has provided an important service in locating microfilm holdings that have proven critical to this project and deserves my thanks as well. All six contributing authors of the Naval War College faculty owe a great degree of gratitude to Evelyn, Alice, and Dennis and all the staff of the War College Library.

Thanks also to Rear Admiral Jay DeLoach USN (Ret.), Director of the Navy History and Heritage Command at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., for his support of this project and our archival research in his fine archives; and to Captain Russ Knight, USN, Chief of Staff of the Naval War College and a senior Navy pilot, for offering us advice on aviation matters and contacts useful to this project.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to my wife, Paulette, who has assisted in proofreading this book and in so many other ways. I thank her also for keeping me flying for over twenty years.

Others who have provided help to all of the contributors but who are not named here are gratefully acknowledged.

The views expressed in this book are those of the authors alone and are not to be construed as those of the Naval War College or the Department of the Navy.

D

OUGLAS

V. S

MITH

Â

Douglas V. Smith

Donato Pietrodangelo

I

f there is one aspect of the United States Navy that has defined its history, and that stands out in its molding of American history, it is Navy Aviation. It is hard to imagine the centrality of the U.S. Navy in America's history without the role Navy aviation has played for almost half its existence. Thus, in 2011 when the Navy celebrates the Centennial of Navy Aviation, it is appropriate that all Americansâand particularly those who have worn the Wings of Goldâtake time to reflect on the monumental impact Navy aviation has had on this country and its citizens.

It is fitting that a volume be dedicated to the pilots who have proudly worn the Wings of Gold, the Naval Flight Officers and the aircrewmen who have placed their

lives in their care, and to the men and women who have kept them in the air for a century. So too is it important that the pioneers of Navy aviation be recognized, their stories told, and that the thousands of men and women who risked everything to make sure the airplanes in the fleet matched the skills of those who would fly them be honored for their innovation, bravery, sacrifice, and dedication.

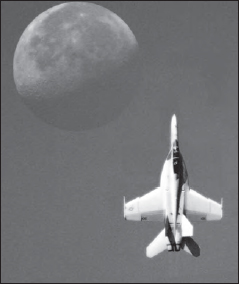

A poem on aviation extols the magnificence of being able to have “slipped the surly bonds of Earthâput out my hand and touched the Face of God!”

1

Few have ever been able to break those bonds and fly. One can only imagine how exhilarating it must have been in 1911 when some had the prospect of doing just that . . . while serving their country and at the expense of the U.S. Navy. In one hundred years, the prospect of the excitement of air flight has not lessened in the American spirit. Living on the edge constantlyâalmost every day of one's lifeâcreates an exhilaration unimaginable to most young people growing up. Strapping on a flame-throwing Mach 2+ rocket today must give a feeling not much different from nestling into a 95-mph biplane with an engine that would not meet the requirements for a good lawn mower a hundred years later. Landing either of these on a postage stamp in the middle of the ocean, inhibited by forty-foot waves and a rolling deck, can only be imagined by someone who has not experienced it. Being referred to regularly as the “best two percent of humanity”

2

for being one of the few who can do just that has produced a confidence unmatched in any fraternity of brothers (and more recently sisters) other than naval aviators of the United States Navy. The pages that follow tell their story.

Today the Commander, U.S. Naval Air Forces is Vice Admiral Allen G. Myers IV, USN. He is in the most fortunate position of leading all Navy aviators as they reach the Centennial year of their profession. It is hoped that this volume, which is intended to tell Navy aviation's story through its first hundred years, might complement the commemorative activities Admiral Myers has planned for the Centennial.

Any tribute to Navy aviation must include a consideration of the pioneers, aircraft, politics, operational concepts, and tactics that together propelled it from primitive aircraft barely capable of operations aboard ships or over vast ocean areas to the most potent and lethal combination of aircraft represented by a modern carrier. Any tribute to what is arguably the greatest leap in technology over a single one-hundred-year period presents the huge problem of what to include and what not to include. Thus the pages that follow have been organized to include as much information as possible on topics of central importance to an understanding of the evolution of Navy aviation as a warfighting tool in the nation's arsenal. Essential to accomplishing this is an understanding of the manner in which aircraft were embraced by the Navy's senior leadership in their nascent state, what roles and missions were envisioned for them, and how those roles and missions evolved and expanded over time.

Additionally, with respect to the capabilities of most likely adversaries, the manner in which Navy Air was introduced into the fleet, the bureaucracy that developed to foster Navy Air capabilities and activities, and the way in which aviation was treated in American war planningâall these issues and dynamics will be addressed in the first part of this book.

The second part of the book is focused on preparations for war with Japan and the totalitarian threats in Europe. Of particular interest are aircraft carrier design and aircraft technology, capabilities and manufacturing developments. The series of twenty-one Fleet Problems and periodic Grand Joint Exercises conducted in the interwar period that enabled Navy leaders to formulate and refine aviation doctrine and tactics are examined. This book looks closely at the competing ideas on the proper mission for American carriers and their aircraft, displacement and design trade-offs, and treaty limitations affecting mission accomplishment. Also analyzed is the need to project technological advances in aircraft accurately to maximize the prospects for success in an increasingly likely war with Japan.

The third section in this volume probes developments in helicopter- and land-based Navy aviation. Most importantly, it considers the huge risk associated with the transition from straight-wing propeller-driven aircraft after World War II to high-speed swept-wing jets necessitated by the Cold War. This section puts these developments in perspective by considering the part played by Navy aviation in the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Finally, a chapter is devoted to postâWorld War II trade-offs in aircraft carrier design and capabilities. This chapter ties in nicely with that on the transition to swept-wing supersonic jets. The trade-off of lives lost and aircraft crashed in bringing American Navy aviation to a state of technological sophistication necessary to support their varied missions today was one realized and accepted by Navy leaders in order to make carriers effective. It is also a tribute to those who have worn the Wings of Gold and their courage and sacrifice. Through the entire hundred-year history of Navy aviation, their willingness to accept the risks of the job has been essential to preserving America's freedoms.

From the first landing and subsequent take-off from a wooden platform on the cruiser

Pennsylvania

by Eugene Burton Ely on 18 January 1911 to the first Navy pilot to set foot on the moon, Neil Alden Armstrong, on 20 July 1969, a mere fifty-eight years had passed. Never in history had such a rapid evolution in a new technology taken place. Keeping pace with this evolution was a similar one in aircraft carriers. Moreover, a blistering change from prop to jet aircraft was under way that was not complete until fleet introduction of the F-18 Hornet on 7 January 1983 and modifications to it that followed. The costs to the men who flew Navy aircraft during this period was tremendous, but progress was steady. Today, thanks to their

courage, sacrifices, and tenacity, the United States Navy has carrier Air Wings capable of responding to crises anywhere around the world.