One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power (33 page)

Read One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power Online

Authors: Douglas V. Smith

Wartime exigency thus played a vital role in carrier construction. With the loss of the battleships USS

Arizona

(BB-39) and USS

Oklahoma

(BB-37) at Pearl Harbor, with the time required to repair and refit the remaining damaged dreadnoughts, and with the attrition of the prewar carriers in combat through 1942, the Navy needed the new capital ships as rapidly as possible. While the older carriers, cruisers, and destroyers of the Pacific Fleet had been able to blunt the Japanese Pacific advance through the various naval engagements in 1942âincluding the battles of the Coral Sea in May, Midway in June, Eastern Solomons in September, Santa Cruz in October, and the multiple actions in the Solomon Islands in support of the Guadalcanal Campaignâby early 1943, the Pacific Fleet had been reduced to two operational carriers: USS

Enterprise

(CV-6) and USS

Saratoga

(CV-3). Any hope of initiating the Central Pacific prong, which reflected the long-standing War Plan Orange calling for a rollback offensive in the Central Pacific leading to a decisive,

Mahanian-style great battle fleet engagement against the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the Philippine Sea followed by maritime interdiction and bombardment of the Japanese home islands, depended on the arrival of the new Vinson Navy. By March 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff contemplated the strategic plans for the war against Japan. MacArthur argued for the SOWPAC campaign aimed at retaking the Philippine Islands. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, as supported ably by his new chief of staff, Admiral Raymond Spruance, the hero of Midway, argued for the Central Pacific advance. In a compromise solution in June 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff agreed upon a dual-pronged advance with the NavyâMarine Corps leading through the Central Pacific island archipelagoes and the Army and Army Air Force with Navy support thrust through the Southwest Pacific (primarily the northern New Guinea coast) toward Rabaul and eventually the Philippines. But a potential problem loomed. The SOPAC campaign had moved along briskly and by early 1943 Guadalcanal had been secured as American forces advanced rapidly up the Solomons chain. In the SOWPAC, MacArthur had initiated operations in New Guinea with Operation Cartwheel in June. So long as the Central Pacific thrust remained a strategy in waiting, the Japanese ability to outflank American and Allied forces from the north, even to the point of cutting off the communications route to Hawaii and the United States, remained an issue. With a robust campaign aimed at the center, Japan would have to defend on many fronts and in many spots to maintain its defensive perimeter, which would of necessity prevent enough concentration of forces so as to threaten the SOWPAC and SOPAC theaters. In other words, the sooner the Vinson Navy could be on station, operational, and ready to fight with new carriers and improved combat aircraft, the better.

American industry answered the call. For example, the contract with Newport News required completion of USS

Lexington

within fifty-seven months of contract award. For the fourth carrier, USS

Randolph

, the contract stipulated seventy months from award to delivery. The date of the contract award letter from the Secretary of the Navy to Newport News was 11 September.

Lexington

was launched on 30 August 1943 and commissioned on 29 November 1943, merely thirty-seven months rather than the contractually required fifty-seven. Similarly,

Randolph

's time to delivery was only forty-eight months rather than the mandated seventy (commissioned 9 October 1944). In like manner, contract deliveries for the Bethlehem Steel Quincy Yard for

Lexington

from time of contract award to delivery took only twenty-nine rather than the prescribed forty-three months, and

Hancock

's delivery in only forty-three months beat the contractual time by twenty-three months.

43

Armed with the new construction ships and airplanes, a testament to the incredible industrial capacity of American industry and the productivity of American workers, the Navy initiated the Central Pacific thrust against the Gilbert Islands with the amphibious assault against Tarawa Atoll on 20 November 1943, an operation that could not

have been even contemplated had not the shipbuilders delivered the new carriers and other ships funded by the Two-Ocean legislation well ahead of schedule. Few archives so vividly illustrate the scope of this economic and industrial power than the 1 January 1943 message to the Commander in Chief (COMINCH), Navy from Captain Donald B. Duncan, USN, Commanding Officer, succinctly stating that “USS ESSEX, CV-9, PLACED IN FULL COMMISSION AT 1700 THIS DATE.” Only thirteen months after the destruction of the Pacific Fleet battleships at Pearl Harbor, the first of the new class of aircraft carriers intended for the destruction of the Japanese Empire, became operational.

44

An additional issue complicated the construction plan. Did the Navy require carriers quicker or a newer, more robust design? The Bureau of Construction and Repair and the Bureau of Engineering (merged in 1940 into Bureau of Ships or BuShips) pointed out in early July, after passage of the legislation, but prior to the president's signature, that to build CVs of the newer design would require additional months compared to using the current

Hornet

-class design. If the first four newly appropriated ships, starting with CV-9, were built to the

Yorktown/Hornet

design, then the estimated time to delivery would be thirty months versus the newer

design requiring forty-four months. Total tonnage did not present a problem with either class design. To build five at 19,800 tons each would bring the program well under the budgeted tonnage. To build four

Yorktown/Hornet

designs and one new design of 26,500 tons came to 105,700 tons or just under the limit.

45

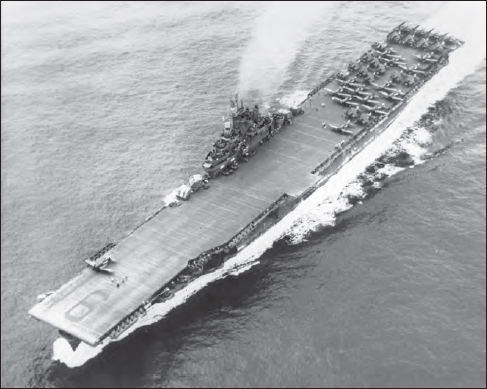

Such were the design decisions facing the Navy as Vinson pushed through ever-greater naval legislation. However, the events of 1940 in Europe had the effect of removing qualms about building the best carrier design available in the most expeditious manner. Accordingly, the Navy decided on the new design beginning with USS

Essex

.

Essex

's design dated to 1939 when the Navy still operated under the terms of the treaty imitations (20,000 tons gross displacement). From a practical standpoint, she appeared much like an improved

Yorktown

class. But, with the outbreak of war and the subsequent renunciation of treaty tonnage limits, the United States removed all restrictions, resulting in the eventual, more robust

Essex

design. An increase in armor and flight deck area gave improved survivability and space for aircraft deck parking. For air defense, the 5-inch guns, mounted in singles on the

Yorktowns

, became twin mountsâtwo turrets forward and two aft of the island superstructure. Engineering space improvements with an alternating boiler room/machinery room design gave better damage control capability. At 872 feet and with a 33,000-ton displacement, the new

Essex

far outstripped the older

Yorktown

-class design. Changes in 1942 included a deck-edge elevator, air and surface search radar, and an increase in anti-aircraft defenses built around the Swedish Bofers model 20-mm and 40-mm rapid-fire guns mounted primarily in rows (20 mm) and quad configurations (40 mm) on platforms and catwalks just below the flight deck. As a result of the decision to proceed with the larger, more capable design, shipyards constructed twenty-four

Essex

-class fleet carriers by war's end with the bulk of the hulls in service by late 1943 to mid-1944, a truly remarkable achievement. From the June 1940 legislation, ten

Essex

-class carriers resulted, all of which saw significant action in the Pacific. Arguably, the single most important American warship of the war,

Essex

slid down the ways on 31 July 1942.

46

Additionally, smaller ship types such as the

Independence

-class (CVL-22) light carrier (launched 22 August 1942) and escort carrier (CVE) emerged from the early war experience. Admiral Stark advised BuShips that a

Cleveland

-class light cruiser originally authorized in the 1934 bill and ordered in 1940 (USS

Amsterdam

, CL-59) would be converted to the new

Independence

-class light carrier as funded by the Two-Ocean legislation. Convoy protection in the Atlantic proved to be a critical mission for naval aviation as German submarines, commerce raiders, and

Luftwaffe

aircraft threatened the logistical supply line to Great Britain and the Soviet Union. Nine CVLs saw war service as well as over eighty escort carriers, starting with the USS

Long Island

(CVE-1) launched 2 June 1941.

47

In October 1940, Roosevelt directed that the Navy obtain a merchant hull for conversion to an escort carrier, resulting in the

first of a long line of highly capable warships used primarily in the anti-submarine warfare and convoy escort roles. USS

Long Island

(CVE-1), converted from the merchantman

Mormacmail

and completed in June 1941, did service in the Pacific in delivering Marine fighter and bomber squadrons to Guadalcanal before returning to San Diego for duty as a training vessel. Roosevelt's plan to convert merchant ships to small 6,000- to 8,000-ton carriers capable of carrying ten to twelve fighters for convoy escort proved a valid concept with the success of the British escort carrier HMS

Audacity

in the Atlantic. With speeds of eighteen knots and better, the CVEs could travel faster than any convoy and almost as fast as the best German submarines on the surface. Primarily carrying

Wildcat

fighters of twenty or more per ship, the CVEs provided substantial air cover for the Atlantic convoys. In the Pacific, they provided close air support (CAS) to the land forces once an amphibious landing had secured the beachhead. In the Leyte Gulf engagement, USS

St Lo

(CVE-63) and USS

Gambier Bay

(CVE-73) sank under the pounding of Vice Admiral Kurita Takeo's battleship-cruiser force. Many CVEs transferred to the British Royal Navy. The Navy designated thirty-five CVEs, constructed or converted under the Two-Ocean legislation, for assignment to the Royal Navy, including eight of the original hulls from 1942.

48

Of the

Casablanca

-class (CVE-55 through CVE-104), the first purpose-built CVEs from the keel up and constructed in the Kaiser Company's Vancouver, Washington, shipyard, all but two served in the Pacific Theater. The late-war

Commencement

Bayâclass ships (CVE-105 through CVE-124), built in the Todd-Pacific and Allis-Chalmers yards in Tacoma, Washington, rounded out the CVEs but only three ships saw combat action. Previous classes had been conversions primarily from merchantmen and oilers. War realities drove the eventual development of designs and capabilities of ships and aircraft, but the funding emanating from the 1940 legislation provided the ability to literally invent new ship types as war exigencies dictated.

These and later ships carried aircraft such as the Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter, Vought F4U Corsair fighter-bomber, TBF Avenger torpedo bomber, and SB2C Helldiver dive-bomber that replaced the prewar design F4F Wildcat, SBD Dauntless, and TBD Devastator types. Funds for the thousands of aircraft of the new types resulted from the Two-Ocean legislation and by 1943â1944, largely replaced the early war models. The legislation increased the number of Navy aircraft to 15,000 as well as the expansion of shore facilities to accommodate the expanded Navy air assets. Forty-two existing naval air stations required substantial upgrades. Many Naval Reserve aviation bases needed modification; seven new reserve bases required establishment.

49

Additionally, the increase in pilot numbers first stimulated by the 1935 appropriation continued as 1940â1942 appropriations dramatically increased the need for aviators. Some characteristics of these new aircraft illustrate the tremendous

advances in naval aviation technologyâcapability and design made possible by the various naval appropriation bills between 1935 and early in the war.

The Vought F4U-4 Corsair first flew on 1 May 1940. With its distinctive gull wing shape and powerful Pratt and Whitney R-2800-18W radial engine that produced 2,100 hp, first production models arrived by September 1942. With a top speed of 446 mph and a 26,200-foot ceiling, the Corsair proved a versatile and deadly fighter and fighter bomber able to engage in air combat and carry both bombs and rocket ordnance. The Curtiss SB2C Helldiver replaced the Dauntless. Designed in 1939, production contracts went out in November 1940, just after the contracts for the

Essex

-class ships. The first combat employment of the airplane occurred in strikes against the Japanese air and naval base at Rabaul on New Britain. The TBF/TBM Avenger first entered combat in 1942 at the Battle of Midway. Designed to replace the unsuccessful Devastator, the large three-man aircraft carried torpedoes, bombs, or depth charges depending on the mission. Despite its durability and survivability, the F4F Wildcat suffered technologically compared to the A6M Zero fighter, and a replacement finally arrived in August 1943. The F6F Hellcat, with a maximum speed of 380 mph at 14,000 feet and a service ceiling of 37,300 feet outclassed and outperformed the Zero in many critical performance characteristics. With a range of close to a thousand miles, the Hellcat gave the carriers an extraordinary combat radius and became the primary naval fighter for the remainder of the war. Aircraft, however, were expensive. A Corsair ranged from $61,000 to almost $70,000 per airplane depending on the acquisition date. A Hellcat fighter ran $54,000. By contrast, the older Dauntless dive-bomber came in at $32,800, while the Wildcat cost $42,000.

50

In the rapid expansion period following the fall of France, the 1940 appropriations provided the funding for the new 15,000-aircraft Navy.