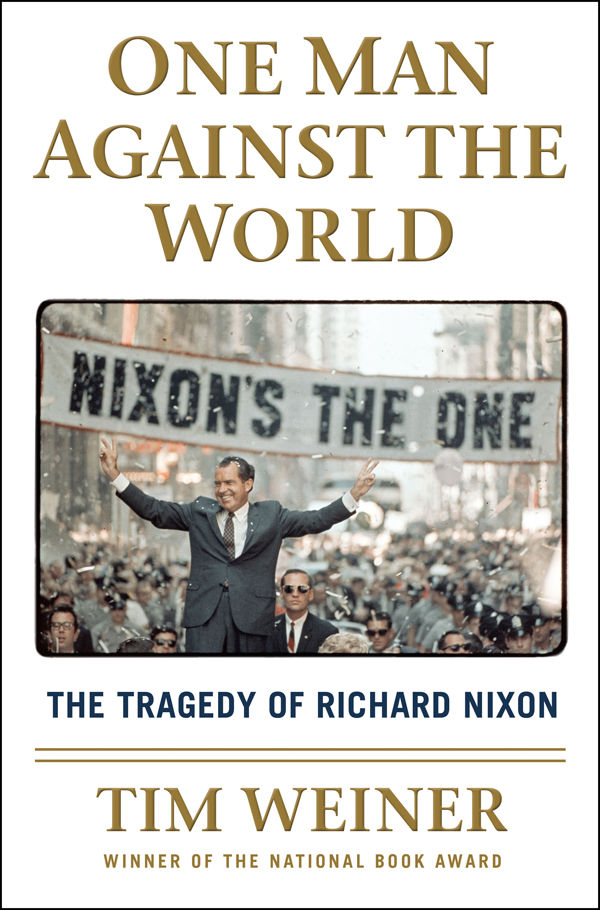

One Man Against the World: The Tragedy of Richard Nixon

Read One Man Against the World: The Tragedy of Richard Nixon Online

Authors: Tim Weiner

Tags: #20th Century, #Best 2015 Nonfiction, #History, #Nonfiction, #Political, #Retail, #United States

President Richard M. Nixon, June 23, 1972—the day of the “smoking gun” tape

Thank you for buying this

Henry Holt and Company ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click

here

.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

To Kate, Emma, and Ruby Doyle, with everlasting love

Balzac once wrote that politicians are “monsters of self-possession.” Yet while we may show this veneer on the outside, inside the turmoil becomes almost unbearable.

—Richard M. Nixon,

Six Crises

, 1962

R

ICHARD

N

IXON

led the United States through a time of unbearable turmoil. He made war in pursuit of peace. He committed crimes in the name of the law. He tore the country apart while trying to unite it. He sabotaged his presidency by violating the Constitution. He destroyed himself and damaged the nation through deliberate acts of folly.

He vowed to bring the tragedy of Vietnam to an honorable end; he brought death and disgrace instead. He practiced geopolitics without subtlety; he preferred subterfuge and brutality. He dropped bombs and napalm without remorse; he believed they delivered a political message beyond blood and fire. He charted the course of the war without a strategy; he delivered victory to his adversaries.

His gravest decisions undermined his allies abroad. His grandest delusions armed his enemies at home. “I gave them a sword,” he said after his downfall, “and they stuck it in.”

That sword was a weapon he forged and sharpened himself. His conduct in office bent the Constitution to its breaking point. The truth was not in him; secrecy and deception were his touchstones.

Yet he had an undeniable greatness, an unsurpassed gift for the art of politics, an unquestionable desire to change the world. He wielded power like a Shakespearean king.

In his eyes, he stood above the law, and that was his fatal flaw, for he fell like a king fated to die in the final act of a tragedy. His arrogation of power created the criminal conduct that his White House counsel warned him was “a cancer within, close to the presidency, that’s growing. It’s growing daily.”

This book is a history of Richard Nixon’s anguished presidency. It concentrates on the intertwined issues of war and national security, because Nixon spent so many of his hours and so much of his power wrestling with those twin demons.

Nixon was the first president I remember vividly. I saw the anger in his eyes and I heard the anguish in his voice as he spoke to the nation about the war in Vietnam. His dark scowl, radiating from our black-and-white television, was an image as indelible as the bloody battles broadcast on the nightly news. I witnessed hundreds of thousands of citizens marching against the war in Washington, while I read that hundreds of American soldiers were dying every week. I talked with my parents about what I would do if drafted into battle. I gasped when National Guardsmen killed four kids at Kent State in Ohio during a protest against Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia. It dawned on me that dissent could be dangerous, even in a democratic country.

Nixon’s grasp on power began to slip soon after he won reelection in 1972 by a margin of almost eighteen million votes, the largest in American history. He was undone by the slow but steady revelation of “the White House horrors,” in the immortal words of John N. Mitchell, Nixon’s former attorney general and campaign manager, one among many once-honorable men who went to prison to protect the president. The Watergate break-in was only one of those horrors, and hardly the worst.

I was riveted by the televised congressional hearings that forced his closest aides to lie about the dirty tricks he had deployed to secure his overwhelming victory. I was transfixed by the intensity of the struggle as the White House battled Congress and the Supreme Court over the president’s prerogatives. At first Nixon seemed to fight under the rule of law rather than the laws of war. Then he fired the attorney general and the special prosecutor in charge of the Watergate investigation; he would risk impeachment and ponder imprisonment rather than release his secret White House tapes. His days were numbered after that blunder. I recall the last throes of his doomed presidency, the pathos of his farewell to the nation.

Nixon has fascinated me ever since. I wrote about his command and control of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation in two books,

Legacy of Ashes

and

Enemies.

As a reporter for the

New York Times

, I interviewed some of his right-hand men, among them Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser and secretary of state. I have discussed Nixon’s legacy with the presidents who succeeded him, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter. I covered the continuing debate over the disgraced president’s reputation and his rightful place in history. So I thought I knew something of the man when I began this work.

Then I dug into a treasure trove of top-secret records from the Nixon years, recently released from the vaults of the government of the United States. This book is based in great part on documents declassified between 2007 and 2014. I read them with a growing excitement. I felt like an archaeologist unearthing the palace of a lost empire.

Tens of thousands of files from his White House, his National Security Council, the CIA, the FBI, the State Department, the Pentagon, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff were newly unsealed. So were minutes of the secret White House committees that controlled military and intelligence operations under Nixon. The transcripts of federal grand jury testimony by Nixon himself, the only president ever compelled to answer questions under oath in a criminal case, were now public records. Hundreds of hours of his infamous tapes finally came out in 2013 and 2014, along with previously classified entries in the daily diary of Nixon’s closest aide, H. R. Haldeman. Together, they ensure that every quotation and each citation herein is on the record: no blind quotes, no unnamed sources, and no hearsay statements.

We have laws governing the declassification of documents and freedom of information, and they endure despite all that has been done in the name of government secrecy in the United States. Without them, the acts that President Nixon hoped to conceal forever would remain state secrets.

What compelled him to commit crimes—secretly collecting campaign cash from foreign dictators and aspiring American ambassadors, wiretapping his loyal aides and distinguished diplomats as if they were foreign spies—and then conspire to conceal them? Why did he drive the nation deeper into Vietnam, at a cost of tens of thousands of American lives, only to accept a settlement no better than the one he could have signed on his first day in office? Why did he lie about his war plans to his secretary of defense and his secretary of state? What were the Watergate burglars seeking? Why did Nixon tape-record the evidence that proved his complicity in the cover-up? Why did he undertake the unconstitutional actions that led to his resignation?

Now we have answers, straight from the president and his closest aides. The story is richer and stranger than we ever knew.

For those who lived under Nixon, it is worse than you may recollect. For those too young to recall, it is worse than you can imagine.

“Always remember,” Nixon said on the day he resigned, “others may hate you. But those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them. And then you destroy yourself.” This story is the tragedy of a man destroying himself.

R

ICHARD

N

IXON

saw himself as a great statesman, a giant for the ages, a general who could command the globe, a master of war, not merely the leader of the free world but “

the

world leader.” Yet he was addicted to the gutter politics that ruined him. He was—as an English earl once said of the warlord Oliver Cromwell—“a great, bad man.”

In Nixon’s first State of the Union speech, he said that he was possessed by “an indefinable spirit—the lift of a driving dream which has made America, from its beginning, the hope of the world.” He promised the American people “the best chance since World War II to enjoy a generation of uninterrupted peace.”

But Richard Nixon was never at peace. A darker spirit animated him—malevolent and violent, driven by anger and an insatiable appetite for revenge. At his worst he stood on the brink of madness. He thought the world was against him. He saw enemies everywhere. His greatness became an arrogant grandeur.

By experience deeply suspicious, by instinct incurably deceptive, he was branded by an indelible epithet: Tricky Dick. No less a man than Martin Luther King Jr. saw a glimpse of the monster beneath the veneer the first time they met, when King was the rising leader of the civil rights movement. “Nixon has a genius for convincing one that he is sincere,” King wrote in 1958. “If Richard Nixon is not sincere, he is the most dangerous man in America.”

Nixon had that genius, a genuine conviction that he could change the world. He was also a most dangerous man.

He had vowed all his political life to fight communism; then he clinked glasses with the world’s foremost Communist tyrants in China and Russia. He gambled on their good faith; he had hopes that they would help him out of Vietnam. He lost that bet. Had he won, he might have remade the political map of the planet. In the long run, at best America broke even after Nixon went to the capitals of world communism. He returned with treaties and statements signifying comity and coexistence, but these liaisons were fragile. They were political communiqu

é

s, not peace deals. Russia and China were our greatest foes then; they remain America’s strongest opponents today.