Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show (30 page)

Read Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show Online

Authors: Edmund R. Schubert

The trigger that resulted in this story was a picture of a doll, with a porcelain mask and a gold and purple robe. I looked at the trigger and, as I usually do, I didn’t sit back and think, I just started writing, thinking as I went. Under ninety minutes later, I had the story. Critiques by the other members of the group helped me to hone it into the right shape, and voilà!

Just in case this all sounds ridiculously easy, I’ve written stories for more than thirty of these challenges (as well as a dozen others, for fortnight rather than ninety-minute deadlines). Some of them will certainly never, ever see the light of day. Others have taken weeks of thought and careful polishing, or even complete rewriting, before they’ve gone wandering out to market. But there’s no doubt that I’ve been a far more productive—and, I hope, far better—writer as a result of these challenges.

3—The Character

Heh. That’s another story. Indeed, that’s a lot of other stories. I’m really hopeful that everyone’s going to be seeing a lot more of Yi Qin. But

IGMS

was her first ever appearance (and my first ever sale), and I’ll always hold it dear.

BY

E

RIC

J

AMES

S

TONE

“Just be

sure of your stroke, son.”

Only I could hear my father’s words over the jeers of the crowd. He knelt down before me and nodded to indicate he was ready. Calmly he raised his head, extending his neck to give me a wider target.

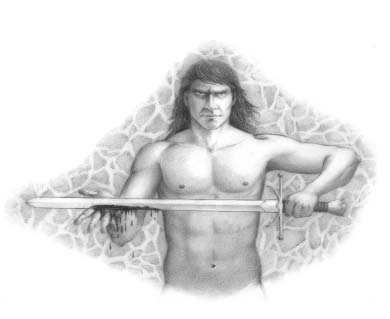

My right arm felt suddenly weak, and my grip on the sword my father had given me for my fifteenth birthday was becoming slippery with sweat. I knew he was no traitor. No one had served King Tenal so faithfully, so long, as had my father. Even as others whispered that the king had fallen to madness, Father’s lips formed no ill word. He had lived to serve the king, but now stood condemned to die, convicted of treason by the mouth of the king himself—no trial necessary, no appeal possible.

I did not feel I could do this. But what choice did I have?

The son of a traitor has the taint of treason in his blood, which can only be cleansed if the son executes his father. If the son cannot do it, he proves his own treason and joins his father in death. But my father had foreclosed that option: “You must remove the taint of treason from our family so that you can care for your mother and sisters. It is your duty to them, and the final duty you owe to me.”

Perhaps the king was mad, but my father was his oldest friend and closest advisor. King Tenal had been like an uncle to me; as a child I’d sat on his lap countless times as he told me stories of the battles he and my father had fought together. He wouldn’t really make me kill my father. I refused to believe that.

Turning away from my father, I knelt before the king. “Your Majesty, by your word is my father condemned to die at my hand. He has accepted your sentence, and has not spoken against it. Does this not prove he is loyal to Your Majesty? Will you not show him mercy?”

The jeers trickled to silence. The king’s eyelids closed, and he muttered while bobbing his head. Snapping his eyes open, he said, “Are you…questioning the justice of our sentence?”

My heart fell. There was no mercy in that stare. Knowing I was a knife’s edge from joining my father, I said, “Your Majesty’s word is law. At your command I will slay my father.”

Suddenly, King Tenal’s eyes rolled up, his eyelids fluttering. A shudder ran from crown to boot and his back arched in a spasm. Two of his guards reached out and grabbed his arms to prevent him from falling out of his throne, while the royal omnimancer swiftly clapped a hand to the king’s forehead and began muttering.

Then, as abruptly as it had started, it was over. He returned his gaze to me as if nothing had happened. “You spoke of mercy,” he said. “Yes, perhaps it is time we showed mercy.”

I stood motionless, hardly daring to breathe. Was it possible that the omnimancer’s treatment had brought the king back to some measure of sanity?

Standing unsteadily, he seized a goblet from a courtier. “We will let the gods decide whether this traitor deserves mercy. We will pour this goblet of wine over his head. If he does not get wet, we shall spare his life.” The king giggled and snorted as he came toward my father and me. Courtiers laughed hesitantly, but the crowd roared as the king upended the goblet, the wine spattering like blood over my father’s upraised face.

“Well, it appears the gods have spoken. Execute him.” Dropping the goblet, the king returned to his throne.

I stood before my father. Though wine ran in rivulets down his face, there were no tears to dilute it. “Tell your mother I love her and was thinking of her. Now carry out your duty.” His voice was low but steady.

Blinking the tears from my eyes so I could see clearly to strike, I positioned my sword by his neck and drew it back. If I struck swiftly and cleanly, he would feel no pain.

I held my sword high, waiting hopelessly for a final word from the king to stay me.

“Do it.” The king’s words were taken up as a chant by the crowd.

I swung my sword. My father was not a traitor. The blade sliced smoothly through his neck. My father had not been a traitor. His head fell back as his body toppled forward, his blood spraying my legs—his blood untainted by treason. For generation after generation, my family’s blood had never been tainted by thought of treason.

Never.

Until now.

Afterword by Eric James Stone

This story began as an exercise in a creative writing class taught by Caleb Warnock:

Show, don’t tell, a person with dignity

.

I thought about various situations in which a character might show dignity, and I decided on a man facing execution. I started writing the scene without knowing much about any of the characters, except for the fact that the man being executed was going to show dignity.

As I wrote, I decided that the executioner would be a young man, new to the business of execution. The prisoner would be an old man, and would actually give friendly advice to his executioner. So I wrote the line “Just be sure of your stroke, son.” (I later moved that line to the beginning.)

And then it hit me—this was not just an old man calling a young man “son.” This was a father talking to his actual son.

But why was the son executing the father? I came up with the idea that it was to cleanse the taint of treason from his family, and the rest of the story flowed from that.

Originally, I envisioned a much longer story, one that followed the young man over several years as he planned and eventually carried out his treason. But Caleb pointed out that nothing in that plot could match the power of the moment when the son is forced to kill his father. So I ended it there.

The inevitable overthrow of the king is left as an exercise for the reader’s imagination.

BY

T

OM

B

ARLOW

Day 1,688

It was my watch. Every time I wake from deep sleep, I have a moment of panic, convinced I’ve slept through some event that has changed the course of human history. My father never forgave himself for falling asleep in his recliner and missing the president’s announcement of our first contact with an alien race. Fortunately, though, most human change is as agonizingly gradual as interstellar flight.

This was my ninth awake period of the voyage, and we’d built up so much velocity that little news from Earth could catch up to us. Although I’d been in deep sleep for six months, there was only a couple of weeks’ worth of news in the queue. No personal messages: That’s why I was in the service to begin with. No strings.

I’ve lived long enough to differentiate “news” from the reiterations of the same old human comedy. People continue to create arbitrary groups so they can fight with people in other arbitrary groups. Those who have a lot continue to try to convince those that have nothing that universal laws are to blame. Meanwhile, people keep butting their heads against those universal laws, and damned if they aren’t beginning to bend. Once I deleted items like those from the message queue, there was nothing left.

I selected some music and soon had the cabin rocking. Control preferred it quiet, but I figured by the time I actually

heard

something mechanical going wrong in the Unit, I’d probably be dead anyway. That’s what it’s like in space; you’re either bored to tears or being sucked into a vacuum. There’s not much in-between.

These kinds of things were going through my mind, which is my piss-poor excuse for not checking on the others right away. I waited for my head to clear and my heart rate to stabilize. I showered. I had a cup of tea and a biscuit. I turned the volume up some more. Control could kiss my ass.

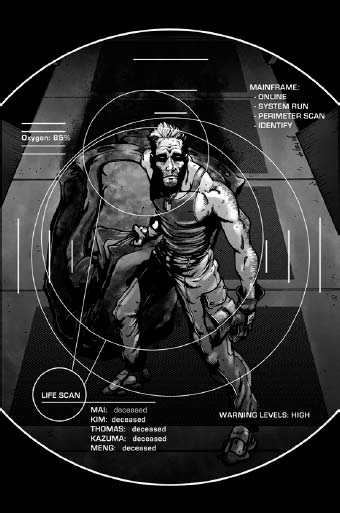

Then I looked at the service log.

We had a cute little routine with the service log. None of us had been awake at the same time since we left five years ago. There were six of us, and we each had to be awake for a week every six months, since that’s the longest you can safely stay in deep sleep without working your muscles, eating real food, and getting some REM sleep and sexual release. (Yeah, I made that last one up. Not proven, but try to find a spacer that disagrees.) Because Control wants the Unit checked as frequently as possible, we stagger our awake periods. Because Control is stingy with the food and O

2

, they restrict us to the minimum time awake.

So we spend a good portion of our waking periods composing witty log entries for one another. Unfortunately, Mai Mu, who precedes me in the rotation, thinks she’s an artist and often fills page after page with her sketches. They resemble a child’s picture of an elephant, every part of the body in a different scale. Or maybe Picasso.

Nonetheless, I look forward to them. Solitude lowers your expectations.

This time, no drawings. No Kuro Kazuma’s haikus. None of Meng’s ruminations on Goethe. No performances by Sir Thomas, who’d carefully hidden his cello the day we embarked because he knew I’d jettison it as an act of compassion for composers everywhere.

No laundry list of duties, staff evaluations, plans, or way-over-my-head technical notes from Captain Kim.

That’s when I thought to check on their well-being.

Until that moment, I never realized that somewhere deep inside, I harbored the belief that losing five friends at once wouldn’t be five times as bad as losing one. I suppose it was doughnut thinking; the first one is great, the fifth is blah.

It’s not true. As soon as I saw the first body, I knew the rest would be dead. The readouts were there in plain sight, right in front of me when I woke up, but I hadn’t bothered to look. I had just assumed everything was all right. Things couldn’t be any less right.

I checked them over one at a time anyway. Every one hurt just as much as the first, or maybe more.

They weren’t smashed-faceplate dead. They were peaceful-sleep dead. They looked like they’d died at about the same time, and not too long ago; there wasn’t a great deal of decomposition.

I’m not a medicine man, but we’ve all had some basic training, including reading the diagnostics. So after I cried a while, ate a big bowl of spaghetti and half a dozen brownies (supplies being suddenly abundant), and received permission from myself to postpone the burial detail, I checked the medical histories.

They didn’t tell me a lot. It was as if their bodily functions, already dialed back by deep sleep to the minimum necessary to sustain recoverable normal life, had just drifted away. The heart rates dropped smoothly from twelve to zero over the course of several hours. The troughs of the brain waves got wider and wider. Body temperature only fell about twenty degrees, to room temperature. I got excited for a minute when I saw the line on the chart start to go back up slightly; then I realized it was the heat of putrefaction.

The life support system seemed to have malfunctioned. The emergency protocols didn’t kick in until they were almost dead. The stimulants, then the shocks, over and over again, only sent them into exaggerated cycles, until a cycle overlapped death. After that, we were just injecting and shocking meat.

I made a mental note to suggest to Control that the pods be equipped to automatically crash-refrigerate the dead until they could be returned to Earth.

For now, though, I had to improvise. It would have been very difficult to thread them into their suits, because they were beginning to melt a little, some skin turning slightly gooey. Instead, I removed their dog tags, zipped each into their own duffle bags, lashed them together, and tied them to the outside of the ship. With any luck, they’d still be there, flash frozen, when we got home. Slow acceleration has its good points, I suppose.

It was queer, but I didn’t feel as alone then as I had when the bodies were lying next to me. I sent a report back home, although I didn’t really need to; the daily readings were automatically fed back to base. There wasn’t a damn thing they could do about it anyway.

It is only now, after I’ve slept real sleep for about two days, that I’ve begun to consider what comes next.

A lot of redundancy had been built into our mission. Six of us had been sent on what was essentially a two-man mission, so that we had a backup crew and a back-backup crew, just in case. We carried enough provisions for twice our anticipated time in space. At the time, I thought it was overkill. I’ve since changed my mind.

I’m in a quandary about resuming deep sleep. If I keep my normal rotation, the Unit would be unmonitored for six months at a time, rather than a few weeks. We could drift irretrievably off course in six months. If I don’t hibernate, I’ll burn up at least fifteen bioyears twiddling my thumbs alone in a thirty-cubic-meter room with nothing but my doppelgänger to keep me company.

OK, truth is, that isn’t foremost in my thoughts. Fear is. I’m scared to death of returning to my pod. I’m obsessing over the fact that there are five dead people outside, who died in deep sleep for no discernible reason. If I were a gambler, I know where I’d place my bet on the viability of the sixth crew member, once he goes back under.

Day 1,692

Control equipped Mainframe with a huge entertainment library. It’s come as a surprise to me just how useless that collection is. I’ve tried all kinds: 3-D, 2-D, role playing, fantasy. I can only take a few minutes of any of them, though. The more images of people I see, the lonelier I become. Like pornography.

Day 1,694

Tomorrow I’m scheduled to go back into deep sleep. I spent today reviewing what I know of celestial mechanics. All I accomplished was confirming that, left to my own devices, I couldn’t find my own ass with two hands and a road map. I also spent some time reading up on alcohol stills and inventorying the drug supplies.

I know it doesn’t matter anyway. I can’t turn around now: not enough fuel. We need the mass of that sun to swing the Unit around without losing all of our momentum.

What is most frustrating is that the trip will be for naught. The original plan had some of us taking the excursion vehicle down to the planet as we passed it on our way into the system, then rendezvousing with the Unit on its way back out. Now it’s going to be like walking past a pastry shop window without a penny in my pocket. A twenty-year walk.

I field-stripped a couple of the pods right down to the chassis. I found nothing. I checked the air feed and reclamation system. It was A-OK. The nutrition system worked flawlessly. I didn’t see anything in the blood-monitoring system records.

Day 1,695

I actually got to the point of getting dressed, sliding into my pod, and laying my head down on the pillow. Then panic set in. I couldn’t close the lid.

The faceplate looked like a giant hand about to close over my mouth. The skin jets looked like snake fangs. The rush of cool air felt like I’d stepped on somebody’s grave.

Day 1,696

I began going through each of the crew’s personal possessions, looking for clues or direction or, really, companionship. I started with the captain, since

I

was the captain now, and I needed some tips about maintaining crew discipline.

Captain Kim’s locker confirmed my impression that he was the world’s most boring man. There was almost nothing in his kit that wasn’t military issue: no family pics, no diary, no awards, no jujus, no candy, no jewelry, no bronzed baby shoes. At first, all I saw was regulation clothes, an elaborate shoe-shining kit, and some old manuals from the Academy.

At the bottom of the drawer, though, I found a neck chain. There were fifteen dog tags on it. They weren’t dated, but from the patina and, more importantly, by the sequence of political entities they fought for, I could see that they stretched back at least three hundred years. Kim after Kim after Kim, marching, drinking, whoring, fighting, dying in the service of the country du jour.

I took his tag off the chain around my neck and added it to his.

Day 1,697

Today I went through Sir Thomas’s effects. If Kim was parsimonious, Tom was profligate. He had a marvelous hand-carved wood chess set, a Go board with moonstone and hematite pieces, an antique cardboard backgammon board, tiny playing cards featuring the faces of famous composers, and a painted sheet-metal Chinese checkers board with exquisite stone marbles. I found that disheartening; the games all took at least two people to play.

I carefully leafed through his prized sheet music collection, browned and flaking at the edges, carefully preserved in plastic sleeves. None of it was more recent than the twentieth century.

For some reason he had also packed his performance outfit, a tailored black suit, ruffled white shirt, and black boots with shiny brass buckles. Perhaps he thought he might run across an alien civilization that didn’t know his reputation yet.

He also had brought a scrapbook of his performance programs, which dated back to when he was about ten. He’d never played large or prestigious venues, but rarely were there six months between performances, except when he was in the Academy or in space. I hadn’t properly credited the sacrifice it must have been for him to spend years with an audience of five.

He told me before we left that, like it or not, he’d be playing for all of us, a week each six months. Since we would be asleep, there was nothing we could do about it.

“If you could just applaud,” he’d said, “you’d be the perfect audience.”

I knew he couldn’t hear me, since he was floating outside, but I clapped for a while anyway.

Day 1,699

Opened Mai Mu’s locker yesterday, but I didn’t feel like writing about it for a while.

I expected to find it jammed with bad art. I’d seen the sketches, of course, but whenever we talked, which was a lot during our prep since we were often teamed up (we weighed about the same), she talked about all the other art she did: sculpture, ceramics, glass, wood carving. She made it all sound massive.

There was, in fact, a lot of art, but very little of it hers. Half of the locker was filled with exquisite miniatures of famous sculptures, each about fifteen centimeters tall. It wasn’t that I recognized them all, but the name of the piece and artist was engraved on each base. There was the

Burghers of Calais

by Rodin, Modigliani’s

Head,

Donatello’s

St. George and the Dragon,

Noguchi’s

Mother and Child, Brushstrokes in Flight

by Lichtenstein, and others. Each was in its own wood case. Each of the bases was a little worn, like someone had held it in her hands for a long, long time.

She was also a diarist, but wrote in Chinese. I couldn’t read it, but Mainframe could.

I never knew she felt that way about me. She seemed so assured, so professional, so decisive, so damned competent. I could have gone the rest of my life not knowing how she was attracted to me, or feeling the regret that came with that knowledge.

Day 1,700

Today I went through Kuro Kazuma’s things.

What a slob. I hate cockroaches, and thanks to his habit of hoarding crumbly cookies, we had them. You know what’s worse than stepping on a roach when you walk into the kitchen without turning on the light? Waking up with one floating an inch from your mouth, and not knowing if it was arriving or leaving.

Luckily, we had enough spin to keep the crumbs from floating away, so I shook out his stuff and swept up what fell.

He had a lot of civvies for a military guy. I had a hunch he didn’t bother to wear his uniform when he was awake alone. I can’t say much, since I usually don’t wear anything at all when I’m the only one awake.

He had some strange-looking outfits, historical stuff. There were several silk robes, which were entirely too small for me; he was a slight man. There were a couple of hats. The bright green silk fez fit me just fine.

At the bottom of his locker was a sword in a heavy leather scabbard. The long curved handle was ivory, elaborately carved with dragon heads, tails, talons, and little people in various stages of being devoured. I carefully drew the blade. It sounded sharp against the sheath, utterly smooth and foreboding.