Outposts (3 page)

But today none give the Empire, even though it exists in shrunken form, so much as a thought. No world divides before Britannia’s feet. The United Kingdom, mighty though she sounds, commands little might, wields little power, can number only a few subjects in her sovereign territories. I thumbed through the

Almanack

and did a little mental arithmetic—at the time of the last colonial census, in 1981, there were 5,248,728 people who could justly be called citizens of the Crown colonies—an eightieth of the number noted just fifty years before. And 5,120,000 of those lived in Hong Kong. The remaining fifteen possessions held just 128,000 colonials.

Might it be possible, I mused, to visit all these places and catch, possibly for the very last time before progress and political reality snuffed it out for ever, something of the spirit of the old Imperial ambition—to see what remained, and find out what it had all been like, and why it had been so grand, why it had lasted so long, why it had died so quickly, but yet had seemingly refused to die completely?

Were there really still governors out there somewhere, with their blanco’d topees and plumes of goose feather in white and scarlet? Did British civil servants still look after our far-flung dominions with a sense of romantic fascination, privilege and pride? Was there a little of the colour and pomp and swagger and—dare I say it—the

style

of the old Empire to be found in these forgotten specks left scattered through the seas? I had been in India, and had sensed the Empire in the cool marble of Curzon and the bold sandstone of Lutyens. I had felt it in the echoing halls of Ottawa’s parliament, in great cathedrals in Africa, in fretworked bungalows in jungle hill stations from Malaya to Guiana.

From one end of the world to the other railway stations and dockyards and libraries and botanical gardens and Jubilee Memorial Halls served to remind us of what the Empire had given to her subject peoples. (And there were historical tracts by the ton reminding us what the Empire had taken from these same peoples, and how barbaric and wicked an arrangement it had all been.)

But these were all memories of the thing, reminders—premature,

maybe, but reminders of a sort—that the Empire had quite passed away. Only, as

Whitaker’s

had so concisely shown, it hadn’t, quite. Perhaps, I fancied, the still-living, just-breathing Empire was to be found in these sixteen distant dots. Its life might be drawing peacefully to a close, but it might yet be possible to capture one last vision, hear one last remark, sense one final exhalation of pride, watch one small finale to the glories that once had been. I made up my mind to go, to make what in Victorian times would have been called ‘an Imperial Progress, an Inspection Tour’, to check up—half for the memory of old King George—exactly how was the blessed Empire, what was the state of the fragments that remained.

Out came the timetables and the shipping calendars and the Cook’s

Continentals

and the Admiralty

Pilots

. I pored and checked my way around the Imperial world, working out how it might be possible to make a single journey that would take in every colony that remained. It became clear uncomfortably quickly that the journey would not be easy.

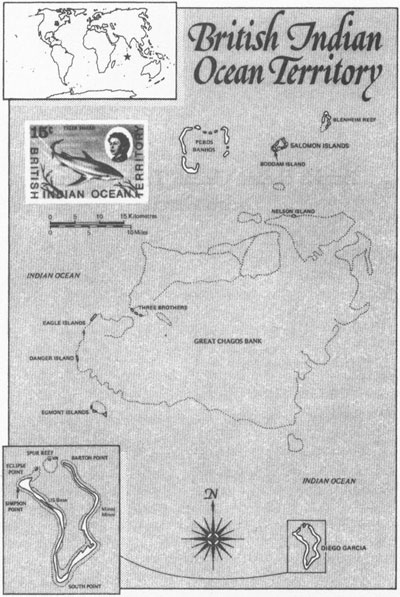

Some colonies were not blessed with aerodromes—not St Helena for example, nor Tristan da Cunha. There was no simple way of getting to the Pitcairn Islands, in mid-Pacific (population forty-four), and it was strictly forbidden for anyone to go to the Chagos Islands, the sole members of the high-falutin’ arrangement known as British Indian Ocean Territory.

Ascension Island was similarly difficult to reach—it belonged to the military, was administered by—of all people—the BBC, was on part loan to the American Navy and was loaded to the gunwales with secret electronics: strangers were discouraged, though not absolutely forbidden.

But my first draft plan disregarded the Cassandras. I felt that, with some perseverance and a great deal of good fortune, I might girdle the world and take in every British possession inside six long months. I would fly from London to Bermuda—no problem here, since British Airways transports thousands of sunbathers there each year. Then I would fly on to the nearest neighbour-colony, the Turks and Caicos Islands; thence to the other Caribbean possessions—the

Virgin Islands, Anguilla, Montserrat and the Caymans. Next—and here was a cunning move, easy to formulate at an Oxford desktop—I would travel from the Cayman Islands to the one-time colony (but now no longer) of Antigua, and catch the once-weekly American Navy plane that I knew took supplies across the ocean to the forces on Ascension.

Now I was on the eastern side of the Atlantic, and fully able to wander down at will, aboard such ships as might tramp by, to St Helena, Tristan, the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the Antarctic bases. I would, of course, be sure to set out from England in the winter: not only would the West Indies thus provide a welcome relief from the cold, but down in the southern latitudes it would be summer, and there would be no problems with bad weather, or with ice.

From Antarctica it would be but a short step to Chile, to an airfield where I could catch a plane to Panama. A passing freighter would then whisk me smartly to Pitcairn Island, and would take me on to Fiji from where I could take yet more planes to Hong Kong. Down then to Singapore, on to another American warplane—how very generous these Americans were going to be!—to their Chagos Island base on the atoll of Diego Garcia—and then, via their good offices once more, on to Bahrein and Tangier. And at Tangier, as every traveller on the north African coast knows well, a plane of Gibraltar Airways waits to carry travellers to the Rock. From there, finally, to London. I would have flown and tramped 40,000 miles; but in six months the Empire would be mine.

In reality it all turned out a great deal more complicated. What I had hoped might occupy six months, in fact took three years. For 40,000 miles, read 100,000. And my fond belief that it might be possible to include all the remains of Empire in one eccentric circumnavigation turned out to be the most wishful of thinking. To make all the right connections, to find yachts, cargo boats, air force jets, scheduled air services, railway trains, open border gates, hydrofoils and ocean liners that went to these tiny blotches of pink that were by now outlined on a map I had pinned to the kitchen wall—to find these, and to organise them, to beg permissions and

to seek new friends, to get time off and to delay deadlines (and to wait for three months while I was let out of prison—that story, which belongs elsewhere, inevitably intrudes into the narrative of one of my visits) meant that, aside from making what an American would call ‘a considerable logistical complexity’ of the whole affair, also forced me to return many times to London. So I would sally out to the West Indies and then, rather than try to travel from the Cayman Islands to Ascension Island, would return home, repack my bags, write more letters, cadge more favours, and set out south again.

And in the end, I made it. The entire British Empire—or at least, the entire populated Empire that was still governed by resident British diplomats—was duly visited. The Imperial Progress was duly accomplished. All governors were visited (save one—an old boy from my school, who was away on furlough when I knocked on his door at Government House in Montserrat); all seals inspected, mottoes read, legislatures (where such existed) visited, lighthouses noted, hills climbed, birds photographed, islanders (for most of the colonials lived on islands) engaged in conversation.

There were also some slight problems with definitions and remits—for in strict truth there are more islands that are dependent territories of the Crown, and which are not normally counted as colonies. The Isle of Man, as that other teatime visitor had suggested, is indeed a territory dependent upon the English Crown, and it is not a part of the United Kingdom. And it has a governor. The Channel Islands enjoy an almost exactly similar standing, too. Should I visit these, and include them in the Progress?

I decided, after some debate with friends and diplomatists who know the details of such things, that to visit Man and Guernsey and Sark and the other islands and rocks nearby would be to introduce red herrings into the story—if only (for there is no

logical

argument for excluding them) because these were places that had been so closely interwoven with national British life for so many centuries that they were wholly free of any feel of Empire about them. True, there was a governor in a large mansion outside Douglas—but he and his predecessors never carried the swagger and the style of true

Imperial governors about them, and his tiny territories never felt sufficiently foreign to be classed as colonies.

My biblical authority on these questions was to be found in a delightful set of little books I discovered in the Codrington Library at All Souls College, in Oxford. (An appropriate library for colonial research, though rarely used as such: Codrington gave it to All Souls essentially as a means of salving his conscience, since he had made his fortunes slaving and sugar-dealing in the British West Indies.) The books, published in 1903, are the four volumes of C. P. Lucas’s

Historical Geography of the British Colonies

, preceded by Hugh Egerton’s monograph on

Colonial Origins

, in which I found the paragraph that settled my mind about which I could visit, and which I would not:

First, then, what is a Colony, according to the common usage of the word? The term, by the common consent of modern nations, includes every kind of distant possession, agreeing herein with the Interpretation Act of 1889, under which the term colony includes every British possession except the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man, and India.

That settled it—almost. One small but important question remained before I wrote to my first friend and booked my first passage. What to do about Ireland? There had been no doubt—Act of Union or no Act of Union—that the Ireland that existed before 1921 had the

feel

of Empire to it. The Irish were a subject people, their status reinforced by the lowering presence of British soldiery in barracks around their country. They were subject, and then they threw off the British chains, and freed themselves, and turned their collective backs on both the Empire and the Commonwealth that took its place. Yet six counties remained, by the choice of most of their inhabitants, held by the British still: Northern Ireland has much the same legal and constitutional standing today as all Ireland did six decades ago. It is a part of the United Kingdom. It sends Members to Westminster. It is not a colony.

But I had lived three years in Belfast, and knew reasonably well that many Ulstermen and women felt, rightly or wrongly, that the

British hold on those six counties had

something

of an Imperial feel to it, and that to understand the dying days of the remnant Empire it would be right and proper to make a brief visit to the last Imperial remnant in Ireland. And so, after argument and hesitation, I decided to go there too—to try to weave a course from Anguilla to Ulster, in other words, and try to discern a common pattern to them all. It was, as I have said, a long and complicated venture.

What follows would have a pleasant neatness were it arranged logically, ocean by ocean, marching down the lines of longitude and along the lines of latitude according to some obvious plan. But my journeys were not like that, and so nor is this account like that. And it begins, not with the colony that is closest to the mother-country—that would be Gibraltar, which a jet can reach in little more than ninety minutes from Gatwick (though in fact I walked there)—but with the colony that is, if not the most distant, then certainly the most remote.

There are islands in the Empire that are themselves more removed from civilisation. Some of those I mentioned at the start of this chapter—Elephant Island, or Zavodovski Island—are merely notations in a colonial clerk’s ledger, and a matter of brief excitement only for oceanographers or the authors of

Pilots

. There is no argument that the four Southern Pacific islands of the Pitcairn group—Pitcairn herself, and the coralline knolls of Ducie, Oeno and Henderson nearby—are the uttermost parts of the populated Empire. But they have no governor, nor an administrator, nor any visiting outsider who serves to remind the forty-odd inhabitants of their colonial status.

No, the island group that seemed to me, from my maps and charts arranged on tables and walls and on door-backs in every room of the family house, to be most precisely an

outpost

—a remote colonial settlement, detached, lonely, and tragic—was sited in the very centre of the Indian Ocean, three thousand miles from Africa, eight thousand miles from home. Moreover, this one colony was, because of the dark secrets buried there, a place you weren’t allowed to visit. I had asked, and had been turned down—and the refusal rankled. So one blazing May afternoon I packed my bags and

sea-sick pills and set off for what the Government, in their current Imperial despatches, refer to as the Crown Colony of British Indian Ocean Territory. The rest of the world knows it by the name of the largest of its myriad islands—a fourteen mile long strip of sand and coral and palm trees named after the Portuguese who first set eyes upon it four centuries ago—Diego Garcia.

British Indian Ocean Territory and Diego Garcia