Outposts (9 page)

The officers left to seek instructions from the island Administrator, a Foreign Office man named John Topp. (The Administrator presides over surely one of the most curious assemblages of Imperial rulers ever—Naval Party NP 2002, with a lieutenant-commander, twenty sailors and six female cipher clerks; a magistrate and a doctor; and six Scotland Yard policemen, who are permanently occupied trying to investigate the innumerable cases of narcotics use among the 2,000 Americans who live on their side of the cyclone fence. This may be an American base; but British justice rules, and so the Foreign Office has to see that the island does not succumb to utter lawlessness.)

While we waited, we watched the vast panorama of the American war machine. Ahead, directly under the bow, was the runway—nearly three miles long (and being extended on stilts into mid-lagoon), and the best equipped between South Africa and Australia. There were six of the silver Lockheed spotter planes parked on the apron, and two more roared in as we watched; ten white-painted fighters, quite probably from a carrier lurking somewhere nearby, were clustered by the control tower; and at the far end, near the storage tanks and some ominous-looking mounds of earth, the gun-grey bulk of a B-52 bomber, all the way from California by way of Hawaii, the Philippines and Guam, and there to show the Middle East that America had the strategic ability to drop atom bombs, or launch cruise missiles, at a whim.

The base—and indeed all of the Indian Ocean, right up to Mombasa and Kuwait—comes under the command of the C-in-C

Pacific, who is based in Honolulu. He remarked to me once that having a forward line as far away as the Persian Gulf, which his bombers took nearly a day to reach, was inconvenient, to say the least. If the Commander of US Forces in Germany wanted to know how it felt, the Admiral remarked, he should be based in St Louis, Missouri, and try to run a European war from there.

But the real impression of power came from the lagoon, and the gigantic assemblage of naval power and supplies. I could count seventeen ships riding at anchor. Thirteen were cargo vessels, stuffed to the gunwales with tanks and ammunition, fuel and water supplies, rockets and jeeps and armoured personnel carriers, and ready to sail at two hours’ notice. There was an atomic submarine, the USS

Corpus Christi

—a batch of crewmen were even now sailing by in their liberty boat, off to see the delights of the Rock and, presumably, to ferret out some of the eighty women assigned to the base; there was the submarine tender USS

Proteus

, which I had last seen in Holy Loch, in Scotland, and which was packed with every last item, from a nut to a nuclear warhead, that a cruising submariner could ever need; and there was the strange white-painted former assault ship, the USS

LaSalle

, now converted into a floating headquarters for the US Central Command, and in the bowels of which admirals and generals played ‘Games of Survivable War in the Mid-East Theater’, with the white paint keeping their electronic battle directors and intelligence decoders cool in the Indian Ocean sun.

But then Messrs. Eddington and Gover swept back in the

Dunlin Express

. Their faces were set. No, we could not stay. London had directed that we leave the Territory forthwith, and the Royal Navy would tow us out to sea if necessary. If we had any repairs we would have to do them at sea.

But we formally refused to go, and said quite plainly that we were within our rights, could claim Diego Garcia as a port of refuge under an international convention to which Britain and her colonies were signatories. Off roared the

Dunlin Express

once more; Mr Topp was consulted, London was telephoned, and back came the boat, with another one, the

Montrose Express

, in tow. Four

khaki-shirted men stood in the background as their senior stood to make an announcement:

‘I, John Winston Eddington, Marshal of the Supreme Court of British Indian Ocean Territory, do hereby request and require you to remove yourselves and your vessel…’ And at this point I suddenly realised we weren’t playing games any more. We were going to lose—we could have the boat seized, enormous fines levied, possessions confiscated, charges brought under Secrets Acts. So, craven and briefly humiliated, I interrupted. We would go, of course, I said; but we were tired, the weather had been bad up north—could we perhaps stay until daybreak? There was some hurried consultation by radio, and John Eddington nodded his agreement. Till dawn, he said; no hard feelings—a drink in London one day perhaps? Only doing my job, y’know. And off the

Expresses

buzzed, leaving us bobbing in their wake, and then alone in the upper part of the lagoon, in a strange and quarantined kind of peace.

The nights on Diego Garcia are brilliant affairs. The ships are festooned with riding lights and deck lights and illuminations. The airstrip glows with sodium vapour lamps, and the satellite dishes scan the skies bathed in a soft white glow. Aerials wink red and white, strobe lamps flicker, the barrack blocks and the security fences are bright in the blue of the kliegs. Someone ordered that searchlights be directed at us, presumably to make sure we didn’t try to swim ashore; and throughout the night aircraft returning from patrol swept above us, colouring the water with their landing lamps. Kipling may have thought Calcutta was the city of dreadful night; this was the colony of perpetual day.

We didn’t wake at dawn, and by eight the

Express

boats were back, and people were yelling through megaphones at us, telling us to move. We took our time, and ate our breakfast while the patrol boats circled us, like sharks; finally we slipped the buoy lines at noon. As we hoisted the sails we turned south, into the lagoon, and sailed around the

Corpus Christi

, and under the bows of the

Proteus

and the

LaSalle

, while a party of Royal Navy men in a rubber boat escorted us to the lagoon mouth. They waved us out and turned

back to base; we felt the pleasant calm of the shallows give way to the slow swell of the ocean once more, and then the wind took hold, and a strong current, and we were swept away from Diego Garcia for good.

Three hours later I heard a plane above us, and saw the familiar shape and the flash of silver. I turned to see if I could spot the Wht. Twr. Conspic.—but the island had vanished below the horizon. That night the glow was easily visible, and lasted until just before dawn, but it was missing the next night out, and the skyline was uniformly dark. Only the radio told of the American presence—Radio Fourteen-Eighty-Five, blaring its advice on aerobic workshops and US Savings Bonds and drug abuse programmes until it, too, faded in a crackle and a hiss of static, and the island disappeared back into the ocean-bound anonymity it so keenly savours.

It still dismays me that so little anger has been generated inside Britain about the sad saga of the Chagos Islands. It might have been different, of course, had the Labour Government not been the one to initiate the tragedy. We tend to associate the Labour Party with the gentler principles of humanity and human dignity—it is a party that purports to stand for civil rights, self-determination, freedom from colonial tyranny, a slowing of the arms race. And yet it violated all of these precepts by its decisions over the Chagos Islands in 1965 and 1966, and by the actions its officers directed in the late 1960s and the early 1970s.

Had these things been done by a Tory administration, as one would perhaps have more easily accepted, the Roy Hattersleys and George Browns would no doubt have pilloried the decisions, condemned the Government for its barbaric cruelty and inhuman devotion to the arrogance of Empire. But, unhappily, it was these very politicians who directed the tragedy, and so are unable to criticise it in the political arena today. There is a time, of course, when expediency takes precedence over principle; and when that happens, as it clearly did over the formation of BIOT and the expulsion of the native islanders, there is a general understanding that not too much will be made of it all, and people will gradually forget.

And so they do. We reached Mauritius two weeks later, and found the islanders from Chagos assimilating themselves—with resignation, but without resistance—into their new home. They had been offered compensation, had accepted, and were moderately well off. They were beginning to forget that they were British subjects in an alien land; and the world was beginning to forget as well.

But those who run the colony are an unforgiving breed. A few weeks later I heard that the skipper of the

Robert W

. had been called back home, had been stripped of his command, and fired, for giving us help, advice and frozen strawberries out there in mid-ocean. He had helped us briefly delve into this most secretive part of the Empire; and the Empire, irritated and angered, had struck back.

Tristan

Tristan

It was an early November morning at the Zululand Yacht Club. The sky was pale blue and cloudless, and there was the feel of spring in the air. A fresh wind was blowing up from the south-west, and from the nine boats beside us came the familiar sounds of small craft in a port: the clinking of wire halyards against metal masts, the whirring of windvanes and the earnest slap of the tiny waves against well-anchored hulls.

The shipping channel was a hundred yards away, and, though this was a Sunday, the port was busy. The club is at Richards Bay, which the South African Government has decided is to be the pre-eminent bulk cargo terminal between Cape Town and Suez, and that Sunday, like any other day, the approach channels were alive with huge bulk carriers sliding to and fro, arriving empty from Japan and Korea, from Seattle and Valparaiso and Darwin, and leaving full of aluminium, or grain, or copper ore from the mines of the Rand and the Veldt.

Every few moments a funnel would appear above the harbour wall and a long steel prow would ease its way between the buoys and down to the cranes and hoppers of the loading bays. And every other few moments an exactly similar funnel and steel nose would, with even greater solemnity and gravamen, lumber its way, fully laden, out into the long sea. These were not pretty ships: they were quite characterless, immense steel boxes with prefabs for bridgeworks, a few contortions of pipes and a clutch of well-greased winches. Designed solely for the efficient transport of the world’s raw materials—and fed not by stevedores, but by moving belts and computerised cranes—they had no evident concessions to maritime grace or beauty. And Richards Bay was the same: stark, modern,

bright, efficient, and with none of the dirty charm and roguery of an old town by the sea.

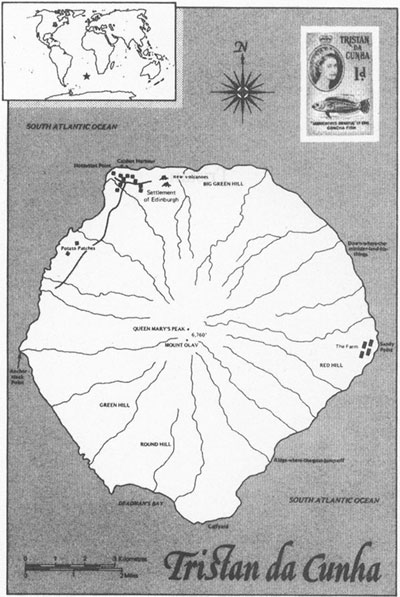

Ruth and I had been stuck there for a week. The south-westerly wind, which all those unlovely bulk carriers could ignore and drive into with aloof impunity, was, for so small a schooner as ours, wickedly dangerous. So long as it was blowing, we had to remain in port. Tristan da Cunha was only 3,000 miles away—a month’s steady sailing, if the wind was fair. But with the south-westerlies relentlessly piling up from the Antarctic, Tristan might have been three million miles away, and after this first week in Zululand I was beginning to fear that my trail to the most remote of Britain’s colonial outposts might never even begin.

The charts and the

Pilots

had warned us. The eastern coast of South Africa, from the Mozambique border in the north to the rocky headland of Cape Agulhas—which, contrary to the popular assumption that the Cape of Good Hope is Africa’s most southerly point, is itself the part of Africa closest to the Pole—has a fearsome reputation. Large, well-found ships have broken up and vanished without trace in the seas beyond these harbour walls. Yachts that risked the coastal waters between Richards Bay and Port Elizabeth, 600 miles away, have, in their hundreds, been driven on to wild cliff-bound shores, have lost masts and sails, have turned turtle, have had great holes gouged in their hulls, or have never been found again.

The coast’s reputation arises from an unusual combination of circumstances. A powerful and very fast warm current—the Agulhas current—flows parallel to the coast, from the north-east to the south-west. In places it runs at five knots: it creates huge eddies and whorls in the water, and navigators can detect its malevolent presence simply by dipping a hand into the sea: if it is unusually warm, then that is current water, swirling and streaming south-westwards towards the southern cape. The current itself might not pose problems—except for ships wanting to drive against it—were it not for the certainty that, for at least two spring days out of five, the prevailing wind that blows above is

from

the south-west. A huge body of water is thus running down towards the south-west, and a

huge body of air immediately overhead is running the exact opposite way. The charts, in a box outlined in red and displayed at intervals along the coast, explain what happens: ‘Abnormal Waves’ a warning declares. ‘The coincidence of contrary wind and current patterns beyond the one-hundred-metre line can produce abnormal waves, with very steep leading edges and exceptional strength. Mariners are advised, in the event of winds from the south-westerly quadrant, either to remain within the hundred-metre contour, or remain in shelter, where available.’

I had read a little of these legendary waves. Other yachtsmen in the club bar added their own warnings. No one—not even the most carefree of the sailors who came in here—underestimated their power. There were magazines strewn around the bar, their pages opened to terrifying accounts of recent experiences. ‘These waves are like nothing anywhere in the world,’ one American magazine quoted a Dutch tanker captain as saying. ‘They are not only enormously large. They are incredibly steep, so that when you reach the crest of one you tip down into what looks like a great black hole in the ocean, you slide down and down, and as you do so the next crest of the next wave breaks down on you and hundreds of millions of tons of water smashes on to your deck and drives you deeper still. Even the most well found steel ship can find it hard to survive an onslaught like this for long.’ The master in question had suffered damage that looked more appropriate to a naval battle: his entire bow section had been ripped away, and all his deck equipment, his foremast and his capstans, had vanished. He had arrived in Durban a sober and frightened man, and, the magazine said, had been flown back by his owners, and was recovering from his ordeal, far from the sea.

And so we stayed in port, day after tedious day. Each morning we would walk to the public phone booth at one end of the dock and call the airport for the weather report. Each day the man on the other end would report back that low pressure zones at this point, and at that point, were causing strong south-westerly winds from Port Elizabeth north to the Mozambique Channel. He came to recognise my voice after a few such morning calls. ‘Bloody frustrating, isn’t it? Best to

keep out of the water, I think.’ One day we did set out: the winds had died, and the coastal radio station thought we might have twenty hours of calms, enough time to get down to Durban. But within an hour after we had cleared the harbour entrance buoys I saw a long black line of cloud ahead of us, and a ferocious mass of dark water roared towards us, and within minutes we were plunging deep into troughs of sea and gales were howling through the shrouds. We dropped sails, turned about, and fled for home and the tedious comfort of our mooring.

After ten days, though, we had some success. One good day took us down to Durban, where we met a young sailor who was able to give us good advice for the next leg of the trip, to East London and Port Elizabeth. His plan, which he had followed on more than a hundred southbound ventures, was to wait until a stiff south-wester was blowing, and leave after it had been blowing for twenty hours—while, in other words, it was

still

blowing. That way, he assured us, we would have an uncomfortable first few hours, would then run into a day of calms and light airs, and would then pick up the north-wester that inevitably came after the southerlies.

He came down each morning with weather charts and new advice. One day we told the port authorities we would leave at four that afternoon, and the immigration and customs men came down and checked us, and stamped us out. But we were then told it might be better to leave at eight, and the customs and immigration men insisted on coming a second time, and charged a fistful of rand for the privilege. Finally, we left at midnight, on the tide: the men with their briefcases and sealing-wax embossers and lead-clamps—for the South African bureaucrat is a great one for paraphernalia—came down a third time, took another ten rand from us, and waved us off into the night, and watched us as we hoisted sails for the 300 miles ahead.

‘Between Durban and East London there is nowhere to run,’ we had been warned a score of times. The coastline—the ‘wild coast’, as the tourist brochures charmingly call it—has no safe harbours to run to in the event of trouble. The coast is, indeed, a fine example of the iniquity of the South African regime: most of it belongs to

the Transkei, an artificial homeland for the blacks whom the whites don’t wish to have living alongside them. And yet the coastline of the Transkei has no port: there is no way the Transkeians—who, the South Africans insist, are an independent people, with all the privileges of nationhood open to them—can fish, or trade, or develop useful harbours. There are South African ports to the north of the Transkei—Durban is one—and there are South African ports to the south—like East London and Port Elizabeth. But the land that has been given to the blacks is, from a maritime point of view, quite useless.

It was an uncomfortable journey, but a safe one. There is a point, off a small bluff known as Port St John’s, where the hundred-metre contour comes to within five miles of the coast, and scores of ships eager to keep out of the way of the dreaded waves were crammed into the passage, making for an unpleasant degree of congestion. But once past that, the fair winds and a current that added its five knots to our four of sailing speed pushed us down to East London in two days. It was three weeks since my plane had touched down at Durban: we were just 600 miles down the coast, Tristan was more than 2,000 miles away, and Christmas was looming. I had brought Christmas post for the islanders: I began to wonder if I would be able to deliver it on time.

The winds were against us for four days in East London, though it was sunny enough, and warm, and the time went pleasantly as we idled in the sunshine, painting and varnishing, repairing the headsail that had torn, lubricating the gaff rubbers with neatsfoot oil, reordering the charts, cleaning the autopilot and generally preparing the boat for the long run ahead. One Saturday afternoon I saw a man sitting on the quayside with his small son, and begged a lift to a petrol station so that I could fill the carboy with fuel for our little Lister engine. He was an electrician, Martin Smyth; his son was Ralph, eight years old. The two came down to the docks every Saturday afternoon ‘just to look at the boats, and dream a little’.

I told him where we were going, and his eyes widened with delighted envy. He had wanted to visit Tristan all of his life—‘leastwise, ever since that volcano that went off—when was that,

’61 wasn’t it? A most fascinating little place. I hope you’ll write and tell us what it was like!’ And he began to explain to Ralph, who wasn’t bored at all, and shared in his father’s very keen enthusiasm, precisely where Tristan was. He knew all about it: he knew the names of the other rocks in the group—Inaccessible, Gough, Stoltenhoff and Nightingale—and something of the names of the seven families who lived there. (He remembered Swain, Glass, Repetto, Lavarello and Rogers. The two he couldn’t recall at first were Green and Hagan, but when I reminded him he then told me that Green was indeed a corruption of the Dutch surname Groen, and that the ancestral Tristan settler of that name was a crewman on the American schooner

Emily

from Stonington, Connecticut, which was wrecked in 1836; he had been Pieter Willem Groen, and had come from the North Sea village of Katwijk aan See: when he decided to settle on Tristan and take British nationality he changed his name to Peter William Green. He became mildly notorious some fifty years later when a parson named Dodgson—Lewis Carroll’s brother—came to the island and recommended evacuating the entire community for its own spiritual good. Green wrote a long letter to the Admiralty protesting at Dodgson’s plan, and was allowed to stay on.)

I spent the rest of the day with the Smyth family. A small daughter was collected from the local cinema, and the children spent hours clambering in the rigging while we sat in the cockpit, drinking tea, and listening to their father’s dreams. Ruth mentioned that once our voyage to Tristan was over she might be selling the little yacht, and she named a price: Martin fell to counting his assets, and wondering out loud if it might not be an admirable idea to leave his electrician’s job and sell his house in East London, and take his wife and children around the world, and to all the little islands—like Tristan—about which he had read. He knew something of sailing: he had owned a small dinghy which he sailed at weekends on a lake in Rhodesia—he refused to use the more modern name—and he imagined he could handle this neat little schooner at sea. He called the children down from the mainmast, and the three went off happily, talking animatedly about what they might do.

We made the boat ready for sea shortly before sunset, and were about to cast off when there was the toot of a car horn, and the entire family—Mrs Smyth as well, on this occasion—arrived to wish us well. They had brought cakes and bottles of beer for us, and Mrs Smyth had made egg sandwiches. ‘You wouldn’t believe how excited they all were when they got home,’ she said. ‘Virginia came dancing in to the kitchen shouting, “Daddy’s bought a boat! Daddy’s bought a boat!” He knows as well as I do that we could never afford it. But it has made them all very happy. It’s been a Saturday afternoon like no other.’

They stayed for tea and then, as the sun began to slope down behind the lighthouse bluff, they said their goodbyes and waved us off from the quayside. We chugged slowly down the Buffalo River, past the rusting freighters and the derelict tugs—for East London is not the port it was, and handles only a few hundred tons of grain and ore each month—and past the yacht club and into the harbour mouth. There is a green light mounted on a tall steel pole on the end of the north mole, and as we rounded it and hurried to raise the sails to catch the evening breeze, so we spotted a familiar car under the flashing lamp. Four tiny figures—two tinier than the others—were waving sadly, and I heard one voice blown thinly by the gathering breeze, ‘Say…hello…to…Tristan!’ Then the darkness enveloped them, and I thought I saw the pinpricks of the car lights as it drove away to a quiet evening at home. I felt suddenly very forlorn, and I daresay they did, too. The children would be bouncing in the back of the car, talking at school next Monday about the boat that they were going to buy and the islands they were going to visit. But in the front seat there would be an uneasy silence, for the Smyths well knew the grim economics of it all, and how they would be bound to his job as an East London electrician for many years to come. But still, we said to one another as we rounded out into the rowdy ocean, they had had an afternoon of dreams.