Paperboy (12 page)

Authors: Christopher Fowler

Our garden was particularly disgusting, a lumpy coagulation of dry, dead earth, rampant weeds, house bricks, bits of rusty iron and the odd fistful of rock-hard rabbit pellets. Londoners had become so inured to the sight of bomb damage, rubble and sooty derelict

buildings

remaining fifteen years after the War that they seemed not to concern themselves with gardening. My father would think nothing of having a pee against the collapsed remains of the Anderson shelter if he thought no one was looking.

Television was considered antisocial, so children formed their own social groups which roughly explored their parents’ divisions, without yet feeling the need to create issues of tribal respect. The only real dividing line was class. I knew my parents were poorer than the neighbours (‘But more respectable,’ my mother assured us) and it only made a difference in the way in which I amused myself. Rich kids were always away somewhere; the poor ones stayed at home.

‘You have to make an effort,’ my mother would say, which I knew was her way of suggesting that it might be nice to put down my book once in a while and form a friendship with someone, anyone.

By the age of ten I had outgrown cuteness to become an unprepossessing sight. Skinny, gangling and bookish, as pale as a blank page, with a domed forehead and sticking-out ears, a pudding-basin haircut, sticky-taped glasses, a narrow chin and large brown eyes that easily reflected fright and surprise, I was nobody’s idea of an appealing child. My weight was outstripped by my height, and I was all knees and elbows, so that when perpendicular I looked as awkward as a straightened chicken, and was better suited to lying on my stomach with a novel.

Much of my time was spent traipsing along the deserted suburban streets with an armful of library books, rain matting my hair and steaming up my lenses. At some point reading replaced doing anything else, so that I lived life as an outsider, an observer on the sidelines. In doing so, I was unconsciously copying my father.

I had a few street friends, kids who would play outside

until

the second it got dark, like vampires in reverse – no one was ever allowed to play out after that because it was another sign of commonness. Lawrence was ginger-mopped, with ginger freckles and what appeared to be purple eyes. He always made up his mind about something without getting all the facts – I found out years later that he had become a vicar. There was an arrogant rival from my class called Peter who was so incredibly bright that he had a nervous breakdown on his first day of senior school, much to his mother’s horror and everyone else’s glee, and he was good fun to hit.

There was also Pauline Ann Ward from across the road.

She had a glossy dark bobbed haircut and wore yellow summer dresses and sandals long after everyone else had moved on to jeans. She wore cardigans and Alice bands and had eyes the colour of an August sky. I supposed I was in love with her. One day, purely in the interests of exploration, she offered to take her knickers off for me, even though we were in her garden and it was snowing, but I declined her offer because I was trying to build a sledge. Even so, her proposal was disturbing enough to make me step back through the ice of her father’s frozen goldfish pond.

Girls like Pauline were far more bothersome than books. You always knew where you were with a book. A girl would laugh at your jokes and then snub you for several days, for no apparent reason. She would go out of her way to let you know you were invisible to her, then stare at you with X-ray eyes until you paid attention. She would tease you, pull up her dress, demand to see your willy, ridicule it, then run screaming to her mother when you tried to hit her.

I didn’t understand Pauline, and she wasn’t even a real girl because she had thick legs like a boy and no breasts to speak of yet. Plus, she played with a Noah’s Ark and kept

mentioning

God’s Will whenever I wanted to talk about space monsters.

‘Your parents are funny,’ she said one day as she sat cross-legged on the floor, marshalling pairs of wooden animals into the Ark.

‘What do you mean?’ I asked.

‘They don’t like each other.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘Your dad said he’d like to glue your mum’s mouth shut. If my dad said that, my mum wouldn’t cook his dinner.’

‘My mum’s tried that,’ I replied. ‘When was the last time your dad threw something at your mum?’

‘Good heavens, they don’t fight,’ said Pauline smugly, trotting her giraffes on board. ‘They adore each other.’ Checking that all the animals were safe from inundation, she raised the gangplank. ‘And they love the Lord Jesus,’ she added for good measure.

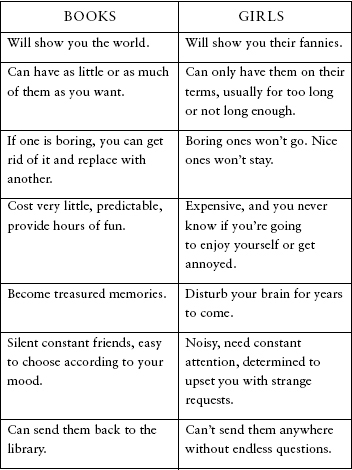

One evening, seated in my bedroom, I tried to work out my feelings about girls by drawing up a chart. Tables, with lists and tick-boxes, always helped to sort out complicated feelings. This one was entitled ‘BOOKS VS GIRLS’.

From this I concluded that books were more cost-effective and enjoyable than girls, but also more predictable and less disturbing. Finding a combination of both was probably the best solution. It wasn’t first love, but it was first curiosity.

Even so, I was better off with a book than hanging around with Pauline, because she took the girl thing to some kind of extreme, like Lois Lane. I decided to return to the library, but would give up the children’s section and put in a request to join the Adults’, even though I was technically too young to do so. Besides, I felt sure that books could teach me everything I would ever need to know about girls, without actually having to deal with them on a regular basis.

1

This miraculously light material grows in South American rainforests. Its seeds are carried like a dandelion’s. It is still used to build gliders.

2

I don’t mean this to sound as if I prefer the toys of the past. I would have given my right eye for an iPod.

3

Mr Bygraves told me that he tried in vain to vary his repertoire when appearing in variety halls, but all the old ladies always yelled ‘Sing “You Need Hands!”’ (one of his more sentimental hits).

4

Corrugated-iron bomb shelters that accommodated up to six people. So strong that you still see them in allotments and back gardens. Ours fell down (not put together properly).

11

Lost for Words

IF THERE WAS

a specific point at which the desire to read transformed itself into the need to write, it must have been here, seated at a scarred desk in the wood-damp library with an immense stack of books before me, far away from harmful sunlight and fresh air. I kept notes of everything I read and liked, along with lists of words that were inexplicably pleasing. Some words could be rolled around the mouth and savoured like melting ice cream. My current favourites were:

Peculiar

Colonial

Ameliorate

Serpentine

Paradise

Emerald

Illumination.

1

There were words I hated as well, ones with sharp edges, all Ks and Xs that dug into you and were awkward to spell. Generally, the rules of spelling and grammar were easy to follow. I could not understand why so many people made such simple mistakes. It vexed me to see the greengrocer placing signs on his fruit filled with random punctuation, like

Potato’s 1/6d

or

“Finest” tomatoes

. I made fun of him so much that he threw sprouts at me.

Mrs Clarke, the librarian, allowed me to raid the reference section and read whatever I wanted, on the condition that I stayed inside the library to do so. Folding my pale bare legs beneath me, I pulled down one volume after another. One book,

Uses of Speech

, stopped me in my tracks because it turned out that there were all these devices you could use to illustrate prose. The first read:

Litotes – the utilization of a negated antonym to make an understatement or to strongly affirm the positive

.

There were dozens of others, each more curious and convoluted in its meaning than the last. I read down the list with a sinking heart.

Metonymy

Anthimeria

Oxymoron

Metalepsis

Antisthecon

Paragoge

Ellipsis

Synecdoche

Epenthesis

Stichomythia

Zeugma

2

What point was there in even attempting to write? If I learned one of the rules, I would need to learn them all. It was what you had to do if you were to become proficient at anything. My father had told me so. Whenever I read a copy of my mother’s

Reader’s Digest

I read the entire thing from cover to cover, including the adverts, even though 95 per cent of it was complete tosh.

‘Christopher, can I offer you a word of advice?’ said Mrs Clarke, sitting down beside me. ‘You don’t have to learn every single thing.’ She smelled of roses and peppermints. She looked dusty and ancient, as old as the volumes bound in cracked red leather that she kept locked up in her reference section, and yet she always seemed to be fighting down a smile, as if recalling a happy memory. She was thirty-four years old, and my mother referred to her as a ‘spinster’.

‘I’m just looking at the rules,’ I told her with a twinge of embarrassment.

‘Oh, they’re not rules. They’re just tools, and not even important ones. You wouldn’t learn how to use a spirit level before you knew what to do with a hammer.’ She studied my profile, my slender hands at rest on the pages. ‘You’re good at English, aren’t you.’ It wasn’t a question.

‘I like books,’ I said simply.

‘The words or the ideas?’

‘Both.’

‘Like writing stories too?’

‘Top of my class in essays. Bottom in arithmetic.’

‘Well, nobody likes a good all-rounder. The love of books is a quiet thing. It’s different to having a passion

for,

say, sport. It’s not a group activity.’ She gestured at the shelves. ‘I don’t own these books, sadly. There are not many things I can give you, but there is something you can have.’ She rose and returned with a slim volume. ‘You can take this one away and look after it for a while. Don’t worry if you find some of them hard to understand; at your age I wouldn’t expect anything else. I’m giving you this so you can see how words fit together. I’ve had it since I was a little girl of ten, and my grandmother owned it before me.’

I studied the cover.

A Child’s Garden of English Verse

. It looked really boring.

Glancing back at Westerdale Road as a young man, I saw the orange-brick terraced homes through yellow rain needles slanting in sodium lamplight, bedraggled little front gardens, the house next door with pearlized shells embedded in its front wall, the Scouts’ hall, the railway line – just like millions of other English childhoods.

And yet there were oddities, like the 1930s advertisement painted on a side wall, gigantic and fading, that showed a smiling housewife pouring boiling water from her kettle on to the surface of her dining-room table; what was it advertising, and why was this demented woman so happily destroying her home?

The twisting alleyways and tunnels behind and between the houses – where today kids would lurk to smoke dope – had been unfenced and completely safe, if a little creepy, but imagining the streets as they had been then, I was impressed by the sheer

lack

of things; there were no mattress farms on street corners, no skips, no dented metal signs, no road markings, no cars, no traffic bays, no yellow murder boards, no charity muggers, no litter, no graffiti, no noise, just the huff of

the

occasional passing steam train, just kids and stag beetles and butterflies and sparrows. You could hear conversation in the next street, and perhaps in the street beyond that.

Despite the sense of community, which everyone said had strengthened during the War, there were still endless household secrets, drawn curtains and muffled sobs, husbands’ dark whispers and wives commiserating, private sorrows, closing ranks, mothers with folded arms staring disapprovingly across the road, children whisked away to relatives because

something dreadful happened that you must never talk about

. Real life occurred behind the walls, between the casual conversations. The woman at the end of the street kept stuffed cats, twenty of them in all, and referred to them as if they were relatives. The man opposite talked constantly, even when he was alone, because during a wartime bombing raid his identical twin had run one way and he another, and his brother had been killed, and he blamed himself.