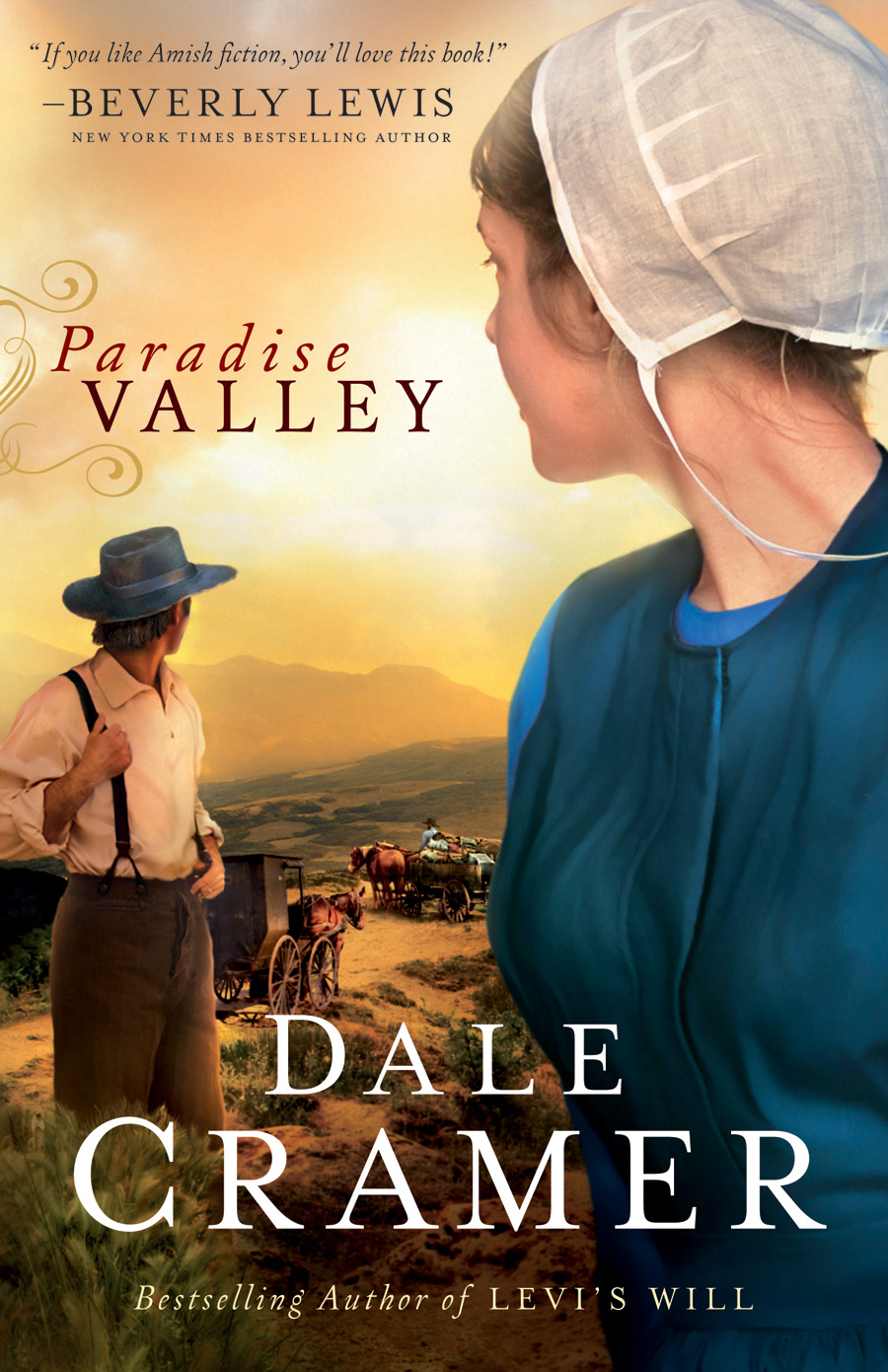

Paradise Valley

Paradise

VALLEY

D

ALE

C

RAMER

© 2011 by Dale Cramer

Published by Bethany House Publishers

a division of Baker Publishing Group

P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287.

E-book edition created 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

ISBN 978-1-4412-1408-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

For my sister,

Fannie Wengerd

T

HE

F

AMILY OF

C

ALEB AND

M

ARTHA

B

ENDER

J

ANUARY

1922

| A DA , 27 | Unmarried; mentally challenged |

| | |

| M ARY , 24 | Husband, Ezra Raber (children: Samuel, 5; Paul, 4) |

| | |

| L IZZIE , 23 | Remains behind in Ohio with husband, Andy Shetler (3 children) |

| | |

| A ARON , 21 | |

| | |

| A MOS | Aaron’s twin brother; deceased |

| | |

| E MMA , 20 | |

| | |

| M IRIAM , 18+ | |

| | |

| H ARVEY , 17 | |

| | |

| R ACHEL , 15+ | |

| | |

| L EAH , 13 | |

| | |

| B ARBARA , 11 |

Contents

In January of 1922 the Salt Creek Township in eastern Ohio was a pastoral haven of rolling hills and curving country lanes lined with horse fences and dotted here and there with the spartan farmhouses of the Amish. Perched near the road in a little bend above a creek valley sat the home of Caleb Bender, a plain white two-story saltbox with a tin roof. Across the gravel drive to the right of the house lay a long, low five-bay buggy shed, and rising from the knoll behind the house a massive T-shaped barn with a tall grain silo attached to one corner. Though nothing about the farm was ostentatious in any way, the whole of it – from the sleek, fat livestock to the neatly trimmed front lawn and flower beds, to the freshly whitewashed board fence around the yard – spoke of order and loving attention to detail.

By sunrise young Rachel Bender and her older sister Emma had already milked the cows and fed the chickens. There were no eggs, for they had been gathered the evening before to keep them from freezing in the night.

The heavy frost turned barbed wire into guitar strings. Rachel’s breath came out in clouds, and brittle grass crunched underfoot as she followed her sister up to the silo after breakfast to throw down fresh silage. The patch of cow-churned mud in the barn lot had frozen solid during the night, and now her toes burned and threatened to go numb, even in boots.

Normally, this would be a boy’s job, but in the Bender family there weren’t enough boys to go around, so the girls grabbed pitchforks and bent their backs to the task. Rachel could handle a pitchfork well enough, though ten minutes of throwing down silage still made her puff a little. Warmed by the effort, she paused for a second to unbutton the neck of her heavy coat.

Emma kept working, humming an old tune, not even breathing hard. Strong, that one was. Neatly parted light brown hair peeked out the front of the black wool scarf covering her head, tied tightly under her chin.

“Are you and Levi going to be married?” Rachel asked, out of the blue. Approaching sixteen, she would soon be old enough to date, so lately she had spent a great deal of time thinking about boys. Levi Mullet had been courting her older sister for almost two years, but so far there were no wedding rumors. At twenty, it was getting late for Emma. Amish girls were always secretive about wedding plans – it was a tradition – so if Levi and Emma were indeed thinking of getting married, it would not be announced until a month before the wedding. Rachel wanted in on the secret

now

– if there

was

one.

Emma stopped and leaned on her pitchfork, grinning at her younger sister’s bold intrusion.

She sniffed. “Well, we

could

be. But don’t you think that would be up to Levi?”

“

Jah

, I suppose, but I’d think you’d know his mind by now. Wouldn’t you?”

Emma smiled and averted her eyes, a clear hint. “I do, and it’s a good mind. He’s a fine man. I’d be proud to be his wife – he already knows that. But he’s also a practical man, and he wants to be sure he can support a family. Anyway, there’s plenty of time. It’s only the first week of the new year, child, and marrying season isn’t until after harvest in the fall.”

Rachel knew her sister well, and the merry glint in Emma’s bright blue eyes told her all she wanted to know. Obviously, Emma and Levi had already discussed these things privately, but it was not yet a matter for everyone else’s ears. The things Emma hadn’t said brought a bold grin to Rachel’s face, her suspicions confirmed.

Emma wagged a finger at her. “Now, don’t you go spreading rumors to all your friends, girl. I’ll thank you to control your gossipy tongue.” But she was smiling as she said it.

That was when they heard the engine.

They froze, listening. Rachel couldn’t see, for there were no windows in the silo, but she could hear what was happening. The automobile coughed twice as the high-pitched clattering slowed to a warbling rumble, and she heard the faint but unmistakable crunch of gravel as rubber tires turned up into the Bender driveway.

She seldom saw an automobile out here in the heart of Amish country, though they had become common in town. Only rarely did a car pass by on the road in front of the house, and none of them had

ever

turned into their driveway before. Dat would not like this. To him, these motorcars were the work of the devil – noisy and smelly and ignorant. Even a

stupid

horse could be made to see reason, but not so a machine.

“Good horses

make more good horses, and they eat hay. The land feeds the horse,

and the horse feeds the land,”

Caleb Bender was fond of saying.

“Gott made it so.”

The automobile, Dat said, was just another assault on the family – like most modern contrivances, a wedge to drive them apart from each other and from the land.

Emma leaned her pitchfork against the wall. “What on earth could

that

be about?”

The noise stopped abruptly, the automobile’s motor clanking and grinding to a halt. Emma backed through the hatch, scrambled down the ladder and ran to the barn door with Rachel close behind. Rachel bumped into her when she pulled up suddenly at the edge of the door.

“Be still,” Emma whispered, peeking out. “It’s probably just some lost Englisher asking directions to Shallowback’s store.”

Rachel giggled at the inside joke. An Englisher passing through recently had stopped an Amishman on the road, asking, “How do you get to Shallowback’s store?” There was a new Amish grocer in town, and the sign over the door read

Schlabach’s

. Englishers’ linguistic offenses were an endless source of amusement.

“You stay here,” Emma said. “I will go and see what it is they want.” She stepped out into the sliver of sunlight between the barn doors, her blue eyes focused and fearless, then turned and gave Rachel a warning glance, shaking a finger at her. “Don’t you move from this spot!”

Rachel’s eyes followed her sister across the barn lot and through the gate before she finally turned her attention to the driveway and took a good look at the automobile parked there. It was the fancy new patrol wagon used by the police – not that different from a surrey except for the small air-filled rubber tires and the funny-looking horseless front end. In place of a tongue there was only an odd-shaped box, like a little coffin, with bug-eyed headlamps. The back half of the vehicle was all enclosed with wood like an ice wagon, except there were rows and rows of holes along the upper part, so if a prisoner was locked inside he could get air. She had seen this monster once or twice before from a distance. The boys called it “Black Mariah.”

The doors opened, and two policemen climbed out of the paddy wagon adjusting their strange, flat, top-heavy hats. The driver’s hair was neatly trimmed and combed, and he was clean-shaven except for a big broom of a mustache. They wore brass buttons on their uniforms. She’d grown up with stories of soldiers with mustaches and brass buttons who persecuted the Amish in the old country, which was why Amishmen would not wear them to this day.

As soon as the two policemen disappeared around the front of the house, Rachel slipped out the barn door and ran across the lot, her ankle-length skirts fluttering in the wind, her heart pounding as she crept past her mother’s dormant kitchen garden and along the side of the house until she could peek around the corner.