Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (42 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Another quarter mile east is a second Belle Époque gastronomic institution, Julien, built for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. With its lapis lazuli peacocks, stained-glass skylights, and rampant floral-theme plasterwork it’s the prototype of the period’s architecture. Here, too, the food hasn’t changed much and neither has the bustling, jovial atmosphere.

It was too early to have dinner, but a coffee at Angelina, on Rue de Rivoli, seemed like a good idea. Unchanged since 1903 (except for a few Art Déco lamps from the 1930s, and periodically refreshed upholstery), this straight-laced temple of

gourmandise

used to be Coco Chanel and Marcel Proust’s hangout, though the plaster-encrusted mirrors now reflect a distinctly New World and Asiatic clientele.

While sipping my coffee I thought about all the places in Paris I could visit if I continued my whirlwind 1900 tour. There was La Pagode, the crazy movie theater made from a Japanese pagoda and opened in 1896, and of course the 1900 Musée Grévin with its theater. Forget the waxworks housed there; the Palais des Mirages, a mirrored hall hung with sculpted elephant heads and snakes, with Fée de l’Électricité lighting, was rescued from the 1900 Exposition Universelle and has been displayed there ever since.

What else was there from the year 1900? The daunting list of sights seemed to stretch forever, from the BHV and Au Bon Marché department stores to thousands of buildings lining the streets. The list was as infinite, in fact, as the city’s seemingly endless turn-of-the-century boulevards. Baron Haussmann’s creative destruction of Paris may have begun in the Second Empire (1852–1870) under Napoléon III, but it was still under way in 1900. No, there was no easy way to draw a line and say, here the nineteenth-century ended, and here the twentieth began.

Hungry by now, I decided to ride the Métro again, down to the Gare de Lyon, and dine there at Le Train Bleu. Both the train station and its luxurious upstairs restaurant were built, like the subway, for the 1900 Exposition Universelle. Unlike the subway and station, however, Le Train Bleu, a landmark, really has not changed.

A dizzying pantheon of plasterwork putti, overflowing amphorae, and fruit-and-floral garlands clings to the heavily gilded neo-Rococo ceiling. Brass, cut-crystal, and carved wood, framed by painted panels showing destinations served by the trains on the tracks below, round out the décor of the dining room, which is a hundred yards long. I settled into a comfortable booth and, after tucking into a Belle Époque dish of

sole meunière

washed down with cool Sancerre, everything became clear. Why were locals and visitors obsessed with 1900 and the Belle Époque? The answer was easy: because many Parisians are still living in the period.

As we see the portals of the latest fin de siècle receding in our rear-view mirrors, the two-faced god of thresholds seems to be staring fixedly at a bygone Paris, unwilling or unable to shake off the past. Perhaps Janus is merely reminding us that in this old Europe of which Paris is still the cultural capital, to look forward we must first look back.

Life’s a Café

[T]he sympathy we felt for the young idlers in the Flore was tinged with impatience: the main object of their non-conformism was to justify their inactivity, and they were very, very bored

.

—S

IMONE DE

B

EAUVOIR

,

La Force de l’âge

t about six o’clock every morning but Sunday, Madame Renée or her husband, José, would drag the banged-up tables and chairs out of their café and set them up on the cobbled

t about six o’clock every morning but Sunday, Madame Renée or her husband, José, would drag the banged-up tables and chairs out of their café and set them up on the cobbled

terrasse

under our bedroom window.

At anywhere from eleven p.m. to two a.m. they would muscle them back in again. Renée did this all her working life and even when still in the womb: her mother ran the café before her. A few years ago Renée and José retired, selling the place to a nearby restaurant. The chair-and-table tradition continues, with thumping music added.

Alison and I have lived above the café for more than twenty-five years or approximately 18,250 chair-and-table draggings. We don’t feel particularly privileged. There are roughly ten thousand cafés in Paris, which I think should consider renaming itself the City of Caffeine and Nicotine. Up and down the scarred asphalt sidewalks, and across the quaint cobbled squares, café owners do the same dawn and midnight furniture dance for Paris’s 2.2 million inhabitants.

That could be enough, you might say, to make us hate Renée, José, their successors, and Paris café owners in general. Never. Well, maybe once in a while we’d love to pour boiling oil from our window, and sometimes I do lean out and shout abuse in several languages. But what would Paris be without its cafés? They’re the stomach, lungs, liver, bad conscience, and, yes, the soul of the city. You buy tobacco in some cafés (

tabacs

), gamble on pari-mutuels or lotteries in others (PMU/Lotto), philosophize, scribble, or surf in yet others (

philocafés, cafés littéraires

, web bars), and drink and eat in all, sometimes well. Romance buds, hatred flares, revelation dawns, violence erupts, fortune smiles upon lucky winners, and smoke gets in everyone’s eyes—on outdoor terraces. Puffing indoors has been banned since 2007.

If nothing else, cafés animate the city, that’s to say they keep it awake with noise and mostly legal stimulants. They’ve been around for centuries: Paris’s first, Le Procope, now a travesty of a café, was founded by the Sicilian Francesco Procopio in 1686. Though there are fewer of them today than, say, twenty years ago, cafés are unlikely ever to disappear. Admittedly the coffee in them is often bad, which is one reason why Starbucks, Columbus Café, and a myriad of other New World–style competitors are gaining ground.

“For the coffee? Good heavens no, I don’t go to a café for that,” remarked a friend of mine, a café connoisseur. “Coffee is simply the cheapest thing you can order while occupying a table for an hour or so …”

It was mid-morning. My friend and I were in the Café Jade on Rue de Buci in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood. I always met this particular friend—recently deceased—in a café. An English woman who lived in Paris more than fifty years, she did her entertaining, held meetings, reviewed scripts, edited manuscripts, and generally enjoyed life in cafés. As we chatted about the institution of the café she took a hummingbird sip at the black tar passing for espresso in her cup. It was not her cup of tea, so to speak, but then the tea in Paris is usually even worse than the coffee.

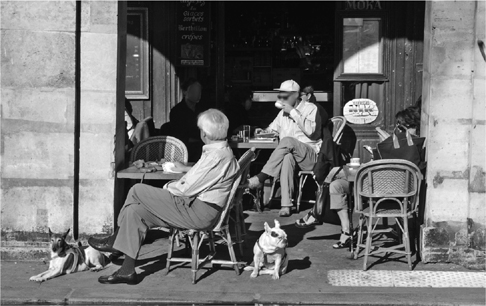

She nodded at the goings-on: waiters whirling among the mushroom-shaped tables, a mixed clientele of aging regulars from the neighborhood, loners, mavericks, tourists, Sorbonne students, and a businessman seated outside on the shaded

terrasse

, shouting into his cellular telephone. Shops were open around the corner so the street swam with colors and movement. Our table was an eddy in this stream: in safety we snapped up snatches of foreign and French conversation, feasted on the sight of passersby, and drank in the kitchen smells of simmering food.

“That’s why one comes to a café, isn’t it?” asked my friend. “For this—the life, the human contact.”

Once the haunt of Paris inevitables like Jean-Paul Sartre, Picasso, Hemingway, et al., the Saint-Germain-des-Prés area may have lost most of its

intellos

(intellectuals), artists, and retinues of sycophants. But its dozens of cafés live on. Contrary to what most visitors think, the Deux Magots and Café de Flore are the exceptions to this rule. Exquisite tourist traps, they are embalmed, mummified, and as such are tremendously popular with non-Parisians.

My friend and I hadn’t really meant to meet at Café Jade, a hipster hangout nowadays. Until the new millennium it went by the name Café Dauphin. Since it was never our regular café, we’d both forgotten about the changeover. Gone are the Dauphin’s booths with their slippery, pumpkin-colored moleskin seats. The Jade first morphed into a retro-theme spot with faux-antique wooden everything, and a salmon-colored neon tube curling across the ceiling. But in recent years it’s gone minimalist, with gray or black everything, and giant lettering that spells out the names of artists, writers, and thinkers who used to haunt the neighborhood but no longer do, either because they’re dead or wouldn’t be caught dead among the current generation of neo-poseurs.

It’s ludicrous to lament the passing of the old Café Dauphin and its hideous 1970s décor, uneatable food, and black-tar coffee. But as my friend pointed out, the décor, food, and coffee are marginal considerations for habitués. It’s the feel of the place that counts, the atmosphere, the spidering relationships between waiter and client, waiter and

patron, patron

and client, client and client.

This web is spun over months, years, even decades. More than anyone, perhaps, photographer Robert Doisneau captured this microcosm of Frenchness in his grainy black-and-white images. They are images that have become icons and clichés, like berets, baguettes,

pétanque

bowlers, and ripe Camembert.

Cheesy cliché or not, today most Paris cafés are still family owned or managed and many are handed down the generations, webs and all. Long taken for granted, these supremely democratic social institutions are a focus of official attention, in part because they are disappearing, in part because a few actually serve decent food and have lured the restaurant critics. Cafés are now reviewed alongside their siblings, the bistros and brasseries. The stumbling café revival got a boost a decade ago with the annual Bistrots-en-Fête, a two-day event held in late September. This contemporary Bacchanal featured dancing, feasting, and drinking, often to excess, and was so successful that it was copied all over France, before disappearing from the radar screens in Paris. It was no longer needed: the Parisian

movida

—a never-ending bohemian bourgeois party—had kicked in by then, transforming cafés into daily party venues.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the high-fashion-lifestyle industry adopted the café concept, wedding it to Food-in-Shop, that paean to consumerism pioneered in the late twentieth century in London and New York. Nowadays chic Parisians buy their DVDs then linger at the Virgin Café in the Virgin Megastore on the Champs-Élysées; they unburden their pocketbooks at Emporio Armani surrounded by fellow X-rays lapping up foamy lattes; or they toy with the accessories at Lanvin on swank Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré before lunching in the modish Café Bleu. Do-it-yourself types head for the hardware section in the basement of the celebrated BHV department store, home to Bricolo Café, which is set in a mock-early-1900s

bricolage

(hardware) shop.

Another twist on the caffeine scene got started in the 1990s at Café des Phares, the first and still most popular “philosophy café” in town. It is perpetually packed by bespectacled

intellos

and posturing

philosophes

carrying tomes by Pascal, Descartes, Camus, Sartre, Deleuze, Baudrillard, and Foucault, and has spawned dozens of similar hangouts.

Such places are a long way from the Procope of the 1600s or the standard nineteenth- and twentieth-century café type run by what’s known as the Auvergnat “mafia.” For a hundred years or more most Paris cafés have been in the grip of Auvergnat families. The “mafia” supplies everything from furniture to mortgage loans, lettuce to coffee beans. Here’s how the system works: starting in the 1800s the Auvergnat came to the capital from the impoverished Auvergne region centered on the Massif Central. They transformed cafés from their earliest Italianate incarnation into havens of the working class, serving food and drink while carrying on their main business activity of selling coal or wood for heating.

This “mafia” is really a mutual aid society, and has nothing to do with organized crime. The rub is that most of the coffee blends the Auvergnat supply their brethren are undrinkable, but everyone has always taken them and those who discontinue do so at risk.

I decided to accompany my English friend to her afternoon café meetings at her then-favorite among the Odéon quarter’s “literary venues.” It’s called Les Éditeurs, meaning “The Publishers.” Several venerable publishing houses continue to operate in the vicinity, and donate many of the books that line the café’s shelves. Les Éditeurs even awards its own literary prize. Like Café Jade and countless others, Les Éditeurs also underwent a radical remodel at the turn of the last century. It was transformed from a kitsch Alsatian eatery. Now it boasts wooden tables and comfortable plush armchairs, tasteful prints, and of course groaning bookcases. French writers and editors actually do meet here. Les Éditeurs has been more successful than most in shedding the moleskin and linoleum and reinventing itself.