Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (35 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

The baron’s was as much a revolution in social engineering as in urbanism. Since industrial workers’ apartments had few conveniences, the empire supplied basic necessities on the sidewalks. For a people who were inclined to build barricades with cobbles piled across narrow crooked alleys, the empire decided to straighten and widen the streets so they could not be easily barricaded and knock down residential labyrinths ideal for guerrilla warfare. Workers needed a modicum of R&R to keep them from rioting? Give them parks and squares where fountains or artificial waterfalls splashed. Military music played from bandstands, reminding citizens who the boss was.

Rioters and road apples were a major preoccupation for Alphand and Davioud. What these architects didn’t have to contend with was the subway, electricity, motor vehicles, telephones, and consumerism—five phenomena that brought about a rejiggering of the city and radically changed the behavior of its inhabitants, from about 1900 onward. Gradually virginal Second Empire streets and sidewalks morphed. First came the Métro entrances, grilles, signs, and maps. Then, as streets and buildings were electrified, hundreds of circuit boxes appeared. Cars, trucks, motorcycles, and buses needed wider lanes, parking spaces, signage, stoplights, gas stations, and, later, parking meters. So the sidewalks were narrowed, trees felled, and benches removed. Along came the telephone and, overnight, booths sprang up on every corner. More people swelled the capital’s population, meaning more street furniture and urinals for busy gents (the total number of

pissoirs

peaked at twelve hundred in 1930, when a campaign to eliminate them began). The postwar throwaway consumer culture and its daily tonnage of trash forced city officials to fit garbage cans into an ever-more-cluttered puzzle.

By 1975, arguably Paris’s modern nadir, the street furniture crisis had become acute. The head of the city’s historical library was moved to begin his preface to an exhibition catalogue entitled

Paris, la Rue

with the words, “The traditional Parisian street is dead.” He lamented that roads were anonymous people-moving spaces and no longer a lively spectacle unto themselves. Soon after that exhibition I arrived in Paris and stayed in Rue de l’Odéon. Little did I know that in 1781 the street had been the first ever flanked by sidewalks. I do remember the congestion of most Paris streets and the decaying, battered objects on them—police call boxes, phone booths, urinals—so full of character.

Since the mid-1970s the pedestrian’s Paris has improved by most measures, despite more cars and motorcycles fouling the air and hogging space. In recent years, sidewalks have been growing wider, with many insulated by bus and bike lanes. The graceful so-called Wallace fountain has made a comeback, as have the slightly older (1868) Morris columns—those comical, onion-domed towers bearing theater posters or, increasingly, JC Decaux advertising. New, free toilets of a Second Empire style are gradually replacing 1980s bunker models. As part of a campaign to green the city, under the tin-eared name

végétalisation

, some eight thousand promised saplings will one day bring the total of Paris trees back to the one-hundred-thousand level of the 1870s. City authorities talk reassuringly about a return to sidewalk “conviviality” with improved hygiene, meaning less dog dirt and redesigned transparent trash cans to replace the current antiterrorism, see-through plastic bags. Step by halting step Paris is rejoining the ranks of the world’s great cities for walking. Perhaps, who knows, one day a contagious form of civility might even affect French drivers, and allow city planners to uproot those ageless

bornes

and

bittes

protecting people from vehicles.

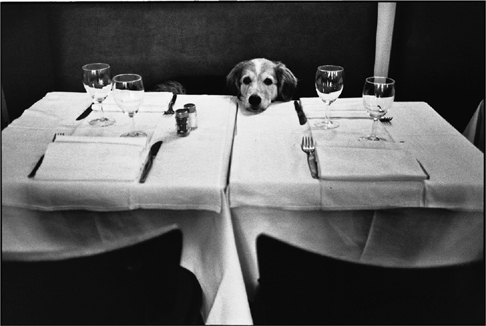

Vie de Chien: A Dog’s Life

Happy dog owners please take note: your companion is surely not vicious but since we wish to maintain cordial relations with him and to preclude any unpleasant eventualities we advise you to restrain him during our visits

.

—Notice to Parisians from EDF/GDF

(the French national electricity and gas utility)

amba! Scirocco! Satan! The trio of Bois de Boulogne dog-walkers called their pets to heel. Alison and I glanced over to see what the commotion was about. The pit-bullish mutt with the spiked collar and shocking name of Satan had tangled pedigreed Samba and Scirocco’s precious Hermès leashes. The three animals and their masters struggled briefly and with aplomb to set things right, then disentangled themselves from each other as quickly as they could. The friction was palpable.

amba! Scirocco! Satan! The trio of Bois de Boulogne dog-walkers called their pets to heel. Alison and I glanced over to see what the commotion was about. The pit-bullish mutt with the spiked collar and shocking name of Satan had tangled pedigreed Samba and Scirocco’s precious Hermès leashes. The three animals and their masters struggled briefly and with aplomb to set things right, then disentangled themselves from each other as quickly as they could. The friction was palpable.

When the incident occurred Alison and I were walking along a tree-lined path near a lake on the fancy, Neuilly-sur-Seine side of the park. As Alison pointed out, there was more to this canine leash conundrum than met the eye. In Paris, dog breeds, dog accessories, and dog monikers have tales to tell—about their owners’ social, educational, and marital status, even their political leanings.

“

Satan

is such a suburban name,” sniffed Samba’s matron as we edged our way by on the lakeside path. Scirocco’s glamorous owner agreed, using a gloved finger to indicate the unfashionable outskirts on the far side of the park, where Satan and his tattooed female owner,

la patronne

, as she put it, appeared to be heading. “You never know anymore who you might meet at the ends of a leash, not even in

le bois

,” Madame Samba acknowledged. The two aging socialites, who did not seem to have known each other previously, now shared conspiratorial confidences as their purebred animals licked and mounted each other.

“Owning a dog,” remarked Alison, a Paris native, “is the best way to get to know people here.” She was thinking in particular of a pair of American friends of ours whose Paris lives bloomed once they bought their adorable border collie, Randy. We often dog-sat Randy, a bouncy black-and-white boy with long hair and a ready smile. Whenever we did, we seemed to meet and exchange civil discourse with perfect strangers—the countless Mesdames and Messieurs of Paris whose last names are in fact those of their dogs. That’s why, whenever we took care of Randy, we became

Monsieur et Madame

Randy—not a bad name to have in a lusty city like Paris.

I’m not necessarily prone to citing statistics, which are massaged by the press, politicians, and the vox populi the world round. But when it comes to Parisians and their dogs, numbers talk. According to recent studies I’ve read, an estimated 16 million dogs live in France, a country with about 58 million inhabitants. That means on average there’s a dog for every three and a half people. Statistics on the number of dogs in Paris vary wildly, from 150,000 to nearly 500,000 (the capital’s human population is 2.2 million). That makes Paris not only the City of Light but also the European Capital of Dog Dirt—sixteen to twenty tons per day—and the world mecca of the Canine Obsessed. The dog dirt is a major health hazard, number two after car-related accidents, and has been the object of many, so far unsuccessful, advertising, poster, radio, and television campaigns whose goal is to toilet-train Parisian dog owners.

Randy’s owners initially shocked the locals by cleaning up his daily mess. As we’ve learned, generally speaking, the Parisian love of domestic animals does not extend to humans, so

les crottes

pile up even in fashionable areas, where to deal with the problem the city initially sent out squadrons of motorcycles equipped with dog-dirt vacuum devices, plus extra contingents of street sweepers with green plastic brooms. Nowadays the canine detritus is also theoretically cleaned up by dog owners—if it’s cleaned up at all. Some years ago I asked several dog-walkers we became friendly with, and even ventured into several pet shops and salons, but no one could tell me how to say “pooper-scooper” in French, or suggest where I might buy one. Perhaps, I reflected, the Académie Française hadn’t yet come up with an official French translation, and the language police had therefore banned the import or manufacture of such suspect implements. Eventually not one but two equivalents were found:

ramasse-crotte

and

toutou-net

. They mean, literally, “turd-picker-upper” and “doggie-clean.” Solving the linguistic conundrum has done little to improve the filth underfoot, though it must be said that in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century the city of Paris began setting up experimental dog toilets in some park areas. Essentially, they’re sandboxes equipped with, for lack of a better term, peeing posts. Some are supplied with plastic bags in suspended dispensers. Panels instruct dog owners to pull off a bag, pick up the poop, flip the bag inside out, tie it, and drop it in a garbage can—standard practice across the Atlantic.

“There are limits,” one dog owner in our building shivered with disgust at the thought of handling horizontal pollution. Her pocket-size terrier has more than once soiled the cobbles of our courtyard, and I mentioned to her the

crotte

bag concept. “You in the New World sometimes go too far,” she scowled.

Maybe. Our concierge wound up posting a sign politely inviting dog owners to remove their pets’

excréments

. Soon thereafter several celebrities and politicos were photographed by newshounds wielding bags and publicly declaiming the merits of dog-related civility. The municipal authorities finally broke down and created a dog-dirt brigade, whose fearless police inspectors lurk behind trees (presumably wearing plastic pants) and leap out, ticket-book in hand, if you don’t clean up after Fido. Fines start low but increase for repeat offenders, and can reach four digits. Having felt pain in their wallets, it’s estimated that nowadays about half of Paris’s dog owners do clean up, at least part of the time.

As to Parisians’ peculiar canine obsessions, they’re another tale. Dogs are the source of pride, prejudice, and big money. Start with the purebred phenomenon. Here as in certain other parts of the world, the first letter in the names of purebred Parisian pooches follows calendar years and the alphabet. That’s why at any one time there are so many Alfas and Artistes or Zebras and Zoros, with all the imaginable others in between. When Sambas and Satans abound, Tommy and Tiger pups soon follow. Those Tituses and Tut-Tuts you knew yesterday when fully grown and replicating will produce Ursulas, Unics, and Uranuses, Venises, Virginies, and Violettes. Odettes and Oscars give birth to Peters and Prunes, Quantums and Quatuors. And so on. The obligatory letter explains why, as you travel around Paris, you keep hearing the same dog names again and again, or diabolically similar variations on them.

Why so many dog names are formulated in something resembling English is a mystery no one has adequately explained to me. Perhaps it’s a subtle way of getting revenge on

les Anglo-Saxons

for a variety of perceived crimes. But I doubt it: Parisians love their dogs more than anything in the world except possibly their cars.

Les Anglo-Saxons

may have invented hero-dogs such as Rin-Tin-Tin and Lassie—real dogs that looked, behaved, and probably smelled like animals—but at some point last century the French hijacked dog-worship and raised it to a higher realm, a place in which curls, perfume, and manicured paws are the ultimate measure of refinement, civilization, sensuality even. What better toy for an aging Parisian vamp than a coiffed lapdog—infant and tender lover rolled into a single, loyal, furry package? And for a graying womanizer with hormones on the wane, a lively, bouncing big dog—a Golden Lab or Rhodesian Ridgeback—could be the ticket to some canine-inspired philandering.

For an ethnically mixed American mutt like me, brought up with casually, often monosyllabically named human friends and mongrel pets rescued from beaches and parking lots, the complexity of Paris’s dog world is baffling. I still do a double take when someone here explains earnestly how Parisian dog owners treat their pets as lovingly as their children—if they have children. The late, great Parisian comedian Coluche once quipped that French families procreate only if they can’t afford dogs. An updated corollary might be, if you can’t be bothered to invest emotionally in your family—your aging parents, for instance—get them a lapdog. Parisian Little Old Ladies and vintage gentlemen, particularly widows and widowers who live to what busy youngsters might consider an overripe age, rely heavily on dogs for company.