Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (101 page)

Do you need to see this child, and are diagnostic tests needed at this point?

Differential Diagnosis

Watery and/or frequent stools may be the initial manifestation of a wide spectrum of acute and chronic disorders, some of which may be life threatening in children. Of particular concern are intussusception, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), pseudomembranous colitis, appendicitis, and toxic megacolon.

Intussusception is most common in infants 6–12 months of age, but can occur later in life; the majority of cases are seen in children less than 2 years of age. Without treatment, it can be life threatening. Most children experience sudden onset of severe, intermittent, crampy abdominal pain accompanied by inconsolable crying. These episodes typically occur at 15- to 20-minute intervals. As the obstruction progresses, the attacks become more frequent and there can be bilious gastric emesis, passage of “currant jelly” stool, and a sausage-shaped mass in the right side of the abdomen. The classic triad of symptoms of pain, palpable sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stools are seen in less than 15% of patients with intussusception. Between episodes, the infant behaves normally, and initial symptoms can be confused with gastroenteritis.

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) should be a consideration for any child with bloody diarrhea. This illness begins 5 to 10 days after the onset of diarrhea, is sudden in onset, and is characterized by the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure (Amiriak & Amiriak, 2006). The prodromal symptoms of abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea that are experienced can mimic those of ulcerative colitis, other enteric infections, and appendicitis.

Pseudomembranous colitis is a rare but serious disorder that results almost exclusively from an overgrowth of toxin-producing

Clostridium difficile

organisms in the bowel. It is commonly associated with antibiotic therapy and prior hospitalization of the child. The typical presentation is lower abdominal pain accompanied by watery diarrhea, low-grade fever, and leukocytosis that start during or shortly after antibiotic administration. This infection can progress to toxic megacolon and shock (Brook, 2005).

Appendicitis typically begins with diffuse abdominal pain with the following three predominant clinical features: pain in the right lower quadrant, abdominal wall rigidity, and migration of periumbilical pain to the right lower quadrant (Paulson, Kalady, & Pappas, 2003). Predictive indicators of appendicitis in preadolescent children include lower right quadrant tenderness, nausea, inability to walk, and elevated white blood cell and neutrophil counts. Diarrhea

may be present in children with appendicitis but is not a useful diagnostic indicator (Colvin, Bachur, & Kharbanda, 2007).

Toxic megacolon can occur as a complication of a Shigella infection, pseudomembranous colitis, Hirschsprung disease, or inflammatory bowel disease. It is a life-threatening complication. Its clinical manifestations are fever, massively dilated colon, painful abdominal distention, and anemia with a low serum albumin level (Bishop, 2006).

In addition to these life-threatening conditions, what other conditions should you include in the differential diagnoses when a child has vomiting and diarrhea?

The following diagnoses should also be considered:

• Urinary tract infection

• Other infections: otitis media, strep pharyngitis

• Inflammatory bowel disease

• Malabsorption: lactose intolerance, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis

• Milk protein allergy

• Chronic diarrhea

• Viral gastroenteritis

• Overfeeding

• Excessive fluid or juice intake

• Amoebiasis

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory testing is not necessary in acute gastroenteritis unless one of the following is present:

• Blood or mucus in the stools.

• No improvement in signs and symptoms after 5–6 days.

• Signs and symptoms of severe dehydration. Specific blood work should be done to check blood urea nitrogen (BUN), white blood cell count and differential, and electrolytes. Urine should be checked for specific gravity.

Testing for a specific virus is rarely necessary because the disease is self-limited. However, if a specific organism is suspected, the following stool tests can be performed:

•

Bacterial infection:

Stool can be sent for culture (e.g.,

E. coli

0157:H7 if child has bloody stools).

•

Giardia:

Send stool for Giardia antigen.

•

Cryptosporidium:

Send stool for ova and parasite test.

•

C. difficile:

Send stool for

C. difficile

toxins text.

Making the Diagnosis

You continue your phone conversation, telling Sara’s mom that you think Sara just has a viral infection that is causing the vomiting and diarrhea, also known as acute gastroenteritis. Some of this may be related to changing daycare centers—especially if other children are sick.

Management

The goals of treatment in diarrhea are to restore and maintain hydration and resume full bowel function as soon as possible. At the least, acute gastroenteritis is a self-limited disease that requires no intervention other than administration of oral fluids and resumption of an age-appropriate diet, as is the case with Sara. Management of more severe illness in children who present with fever and dehydration should include the following steps:

1.

Restore and maintain hydration.

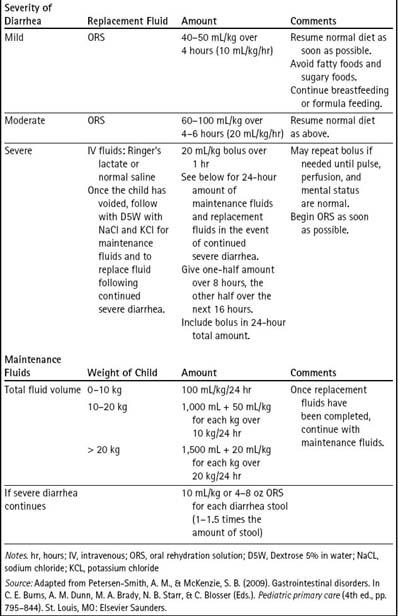

With a diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis, initial therapy is directed at correcting any fluid deficit and electrolyte imbalance. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and World Health Organization (WHO) have established fluid replacement guidelines for children with diarrhea (AAP, 2004; King et al., 2003). All are based on the degree of dehydration or volume depletion. Severe dehydration requires immediate intervention with rapid intravenous fluid resuscitation. With mild to moderate hypovolemia, oral rehydration is preferred, and can be accomplished with oral rehydration solution (ORS) or with the use of a number of prepared commercial solutions. Inappropriate liquids are Kool-Aid, fruit juices (e.g., apple juice), sports drinks, and sodas; gelatin should also be avoided. See

Table 25-2

for recommendations regarding treatment of various degrees of dehydration.

2.

Resume feedings.

Both the AAP and the CDC recommend the resumption of feedings of an age-appropriate diet as soon as rehydration is complete. A relatively unrestricted diet reduces the stool output and the duration of the illness (King et al., 2003). For the infant, on-demand breastfeeding should be continued without disruption when a child has diarrhea. If the infant is receiving formula, feedings should continue unchanged as tolerated. In older children, full strength cow’s milk or other nonhuman milks are usually tolerated without problems. Use of probiotics or lactose-free formulas appear to be generally unnecessary (Salazar-Lindo, Miranda-Langschwager, Campos-Sanchez, Chea-Woo, & Sack, 2004), but in a study of Thai and Asian children with genetic lactase deficiency, acute diarrhea resolved more quickly with a lactose-free formula (Simakachorn, Tongpenyai, Tongtan, & Varavithya, 2004). Foods that have high levels of fat and simple sugars are less well tolerated than complex carbohydrates, lean meats, yogurt, fruits, and vegetables (King et al., 2003). Contrary to practices from years past, fasting or “letting the bowel rest,” and exclusive use of the BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast) or a diet of clear liquids (like apple juice) are unusually restrictive measures and provide suboptimal nutrition for the child. The child should not fast, and the foods in the BRAT diet can be included in a normal diet as tolerated, but should not be the dietary mainstay. Toddlers and older children should eat a wide variety of healthful foods, fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and carbohydrates as tolerated. Smaller portions, given more frequently, may be better tolerated. High-carbohydrate (especially sugared drinks and sugary foods), high-fat, and spicy foods should be avoided. Boiled milk should

never

be given (AAP, 2008).

Table 25–2 Rehydration Therapy

3.

Prescribe appropriate antibiotics (only if an identified bacterial agent is the cause of the diarrhea) and other medications only if indicated.

Do not prescribe diphenoxylate-atropine (Lomotil) because it slows intestinal motility, can contribute to paralytic ileus, and can complicate the clinical outcome if the diarrhea is due to antibiotic administration, pseudomembranous colitis, or an enterotoxin-producing bacteria. Repetitive or incorrect dosing of diphenoxylate-atropine has also been associated with mortality in toddlers (Thomas, Pauze, & Love, 2008). Avoid use of Pepto-Bismol because it can mask symptoms of nausea and upset stomach and may interact with prescription drugs, making diagnosis and resolution of the underlying problem more difficult. Also, the active ingredient in adult preparation Pepto-Bismol, bismuth subsalicylate, has been associated with toxicity in infants (Lewis, Badillo, Schaeffer, Hagemann, & McGoodwin, 2006); the active ingredient in children’s Pepto-Bismol is calcium carbonate, which can be used cautiously in older children.

4.

Administer zinc.

Some studies have shown the administration of zinc to children in developing countries with diarrhea decreases the duration of the illness (King et al., 2003; Strand et al., 2002).

5.

Administer parenteral fluids if signs of severe dehydration are present or if the child is at high risk for rapid dehydration.

See

Table 25-2

for parenteral treatment of severe dehydration. Intravenous therapy may be administered in an urgent care center or emergency department, where the child can be carefully observed. Hospitalization may be required.

6.

When giving a telephone consultation, always tell the child’s care provider when to follow up with the healthcare provider.

They should also be advised to seek care if severe symptoms develop or if the child’s symptoms become worse or do not resolve in a projected length of time. Identify what signs and symptoms are worrisome and require evaluation. In addition, provide a specified time frame in which the child should show signs of improvement. Tell the child’s care provider to seek assistance in an emergency department on weekends or after the clinic or office is closed if necessary.