Percival Everett by Virgil Russell (5 page)

Read Percival Everett by Virgil Russell Online

Authors: Percival Everett

I’ll go out and talk to her.

You do that.

I do not want to know about the human heart. I do not desire to speak at all about those indwelling, intimate reaches of the heart in which anguish is an undiminishing personal interrogation, much less to analytically enfetter those reaches. I have the sense, the good sense, the decency, to have nothing to say.

Dad?

Son?

Dad?

Son? We could go on like this until late into something or perhaps early into the next thing. But what about the man with the horse whose wife is gone and who might or might not be headed toward something intimate with the tough, straight-talking veterinarian? And what of the horse out there with those people whom the trainer doesn’t like? The biting horse and the loud people? Let’s do.

The vet comes back and they slice open the horse’s neck and of course find nothing, but there is the beloved animal with his neck as open as a doctor’s Wednesday afternoon.

The vet says, Leave it open. Irrigate it, but not too much. Let it granulate over and form a big scab. You don’t want to get in nature’s way.

Don’t cover it at all?

She shakes her head and begins washing her instruments in her metal pail of Betadine solution. She looks up, pulls her hair from her face with the back of her hand. Are we going to go into your house and have sex or what?

Yes.

That is one way it could happen. Perhaps not likely. Perhaps a pathetic male fantasy, but however they end up

doing it,

they do it, and so a relationship begins. Man with a horse meets woman who treats horses.

Dad?

Yes?

Will any of this help?

It can’t hurt. This is what I want all of this to do, to be. I want it to sound like nonsense, have the rhythm of nonsense, the cadence of nonsense, the music, the harmony, the animato, the euphoniousness, the melodiousness, the contrapuntalicity, lyrphorousness, the marcato, the fidicinality, the vigor, isotonicity, lyriformity, of nonsense.

Okay, is this Murphy?

Funny you should ask. Because I’m reworking Murphy. Maybe I am. Maybe you are. This horse stuff, I’m just so tired of it.

And the trainer with the loud people?

Fuck ’em.

Murphy.

At my house, which is now in town, my office being beside it in mid-twentieth-century fashion, I put down my medical bag and sit in my leather chair and examine my newly acquired Leica camera. I will have no more patients today. I look through the viewfinder and see:

Charlton Heston, James Baldwin, Marlon Brando, and Harry Belafonte. Sidney Poitier is in the background. And in the foreground, in profile, an unlit cigarette dangling from his lips, is Nat Turner. Nat turns and smiles at the camera.

There’s something about Charlton that I like. His love of guns. If I could have had some guns back in 1831, things might have turned out differently. Right now Chuck is all about helping us black folks, but there’s something in his eyes and I’ve seen it before. He likes being white, really likes being white, and like any reasonable person he has no desire to be black in these United States, but that’s really different from enjoying one’s whiteness. Balance, it’s all about balance.

The telephone rings and it is Douglas calling me. Thank you for seeing my brother.

You’re welcome. So you’re his doctor now.

I look at the Leica in my hand and I cannot put it down. It is fused to me. My fingers stroke the shutter release.

What do we do next? To help him, I mean.

He needs a full blood workup. He needs a treadmill stress test. He needs to stop smoking, drinking, and eating.

The first one we can probably manage.

I’ll call tomorrow and tell him where to go for the blood tests.

Do you like that camera?

Yes, I do.

It’s a special one.

How do you mean?

Only that it’s one of my favorites.

By the way, I can tell the two of you apart now, you and Donald.

That’s funny, no one else can. See you later, Doc.

Thus, if I or you, son, can be relied upon, we are at this moment in time in a most grave condition, besieged and beset by that ceaseless host of negative thinkers and would-be controllers and, yes, disbelievers, threatening to undress us publicly. The world, says you, as it proceeds, is under an operation of devastation and misapplication and abuse, which, whether by creeping and insidious and assiduous corrosion, or open, hastier combustion, as things might be, will efficaciously enough destroy completely past forms and replace them with, well, whatever.

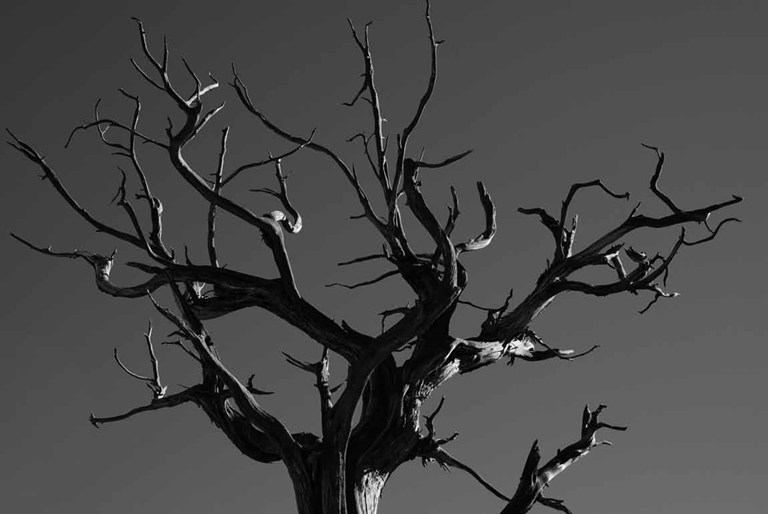

The tree makes you think of that?

Hey, it’s what the camera was pointed at.

Forms of what?

I don’t know. Society? Art? For the time being, it is thought that when all of our artistic and spiritual interests are at once dispossessed, these uncountable shapes to stories must be burned, but the better stories should be pasted together into one huge poem or graffiti for the defense of language only.

And this is how you spend your day thinking?

This is how I spend my day. All meaning must collapse under the weight of its own being.

Do you know how you sound?

I can only imagine.

This is where I pause to mull. You might think that I should be mulling something over, but I am a fan of the simple

mull.

I want to consider the day you were born. There was not a cloud in the sky and there were very few birds as well. Your mother was in the hospital in good time, time enough to even think that she was there too early. These were the days when fathers paced the hallways and waited helplessly, smoking, because everyone smoked everywhere. The obstetrician probably had a Camel filter dangling from his lips as he got a good grip on your oversized head and pulled you into this miserable, good-for-nothing world. You know the world I mean, where the rich get richer and the dumb get dumber and the horny get hornier and the only thing that ever changes is the size of insecure women’s breasts.

Douglas and Donald now live in an apartment building down the street and around the corner, right next to Luigi’s Afro-American Taco Pagoda, home of the Barbecued Cilantro, Salmon, and Prosciutto Roll, known as the Barcisalproro, served with turned cider. They don’t make meth, but they sell drugs out of their home. It’s so much easier and they live closer, in town; that helps. I don’t have to drive. But I do have to walk through my neighborhood, a scary thing indeed, as there are many people who patronize the fat twins and many people who find nothing wrong with what the fat twins do. Let’s say we’re in DC and I live near the corner of 14th and U. Let’s say it and so it is true. We’re here since this camera that I, or whoever this I is, is holding in his lap seems to want to see Washington.

I knew this guy once, he was a writer I guess, a white guy, I introduced him at a reading one time and neither he nor anyone else ever forgave me for calling him the Ralph Abernathy of American letters. A poet, a white woman, asked, pointing a finger at me without actually using her finger, just what I meant. I asked her if she knew who Ralph Abernathy was and she said she did and I said then I didn’t understand her confusion. Another poet, a man with blue eyes and blond hair (because I’m sick of saying

white

), stood up and said he took exception to my comment. I asked him what he had against Ralph Abernathy. He said he held nothing against Abernathy and so I asked why he should be so offended. Is it because Abernathy is black? I asked. He sat down. This was at the University of Iowa in 1976. You were six and hating every minute of first grade. The night before Gerald Ford gave the country a moment of clarity by declaring that there was no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe while debating Jimmy Carter. Granted, it must have been a confusing thing for all those white people to hear and I’m fairly positive that even I didn’t know what I meant by it, but the consternation the remark caused was well worth what little trouble it took to utter it. As I said, you were six, and somewhat unhappy, and it made you unhappier still when I told you that such unhappiness was a condition you would more or less have to get used to if you planned to live into and through adulthood. You mother would not have argued, as she was already considering leaving me, though it would take her another seven years to finally do it. Actually she didn’t leave, she just never came back. She claimed she saw god. She was on a flight from Montreal, where her maternal grandmother lived, to Edmonton, where her paternal grandmother lived, and the Air Canada flight she was on ran out of fuel and had to be glided into a landing at a retired military airfield. She fell in love with the copilot of that flight, a nice Canadian man, and settled down in Ottawa. She never claimed that the flyboy was god, but she said the near-death experience of the emergency landing gave her the strength to seek happiness in her life. I agreed with her and said as much. Gimli, that was the name of the airport where they landed. Funny that I should remember that. I really loved your mother. I was sad when she didn’t come back, but, like I said, I understood and still think it was for the best. For her at least. It really fucked you up. Not so badly as I might have guessed, though. I mean, you’ve grown up to be successful and well adjusted and, of course, unhappy, the way a man is supposed to feel in this world. Just pulling your leg, son.

I started writing in 1970, just after the My Lai massacre. That was quite a massacre as massacres go, five hundred defenseless children, women, and men. We at home (as we called it) were told that it was just an accident of war, but do you kill so many people by accident, and how do you sexually abuse and mutilate people by accident? That guy, Calley, served a couple of years under house arrest and in therapy trying to undo his short man’s complex and now he probably runs an advertising firm in Nashua, New Hampshire, or an oil speculation company in Tulsa, Oklahoma, married to a second wife named Sadie, who is constantly nervous and pissed because his first wife, also named Sadie, keeps calling, complaining that he’s behind with his child support even though the kids are grown and out of the split-level tract home they once shared in Redlands, California, but all that is just in the mind of a bitter old man, namely, me. I’m sure he’s attending a luncheon with a Kiwanis club in Georgia and that he still gets calls from that Medina guy telling him when he should scratch his ass and stiff his fingers, because that’s what good little soldiers do, right? Take orders, follow orders, obey orders, carry orders out, see to it, comply, roger wilco. I can still recall the images, the descriptions, the reported snatches of language from the soldiers involved, the way my heart broke, sank, collapsed, and the way it sounded so familiar, so much like white men in white hoods driving dirt roads and whistling through gap-toothed grins. I did not write about war or killing or overtly about my disdain for my lying, bombastic, self-righteous, conceited, small-minded, imperialistic homeland. Instead, I wrote about getting high, while getting high every chance I got, at every turn, smoking this, swallowing that, all this as a way to escape blame for my country, at least that was my excuse, all of it as a sad, juvenile metaphor about the lost American spirit, the mislaid, impoverished, misspent, misplaced, wasted, suffering American soul. The novel was titled

Pass the Joint, Motherfucker,

and it was published on the first Earth Day, not that it matters, not that I knew that at the time. The book was a success and so I became a success and I never published another word. I wrote plenty, keeping the pages in my drawers and burning them periodically, a haughty and vainglorious display, if you ask me. I gave interviews freely, usually to moderately, though to not overly bright students fresh out of some graduate program or another trying to see their names in the pages of those literary magazines that no one really reads. I contradicted myself from one to the next. I did not grow complacent, I was complacent. I was smug and I was therefore ugly. I was never bitter about my career, but I found it a bit amusing, ironic, ridiculous. Not that my career should have been anything more than it was. To say that I published nothing else is of course a lie. I published eight science fiction novels and twelve detective novels under different names. The science fiction novels, the Plat series, were penned under the name Nix Chance. As a crime writer I was known as Bill Calley. You should know that I’ve never confessed this to anyone. Only my agent knows. It’s a story in the works.

Back up, if you can do the math; that means your mother left me with a thirteen-year-old boy who didn’t particularly like me. Tell me that’s not cruel. To you, I mean. But I liked you well enough. I thought you were funny, sardonic, sometimes a little twisted. Me, I’ve always been just a punster, but you were funny. I suppose you still are, but how would I know?

I call this entification. I mean, as subjective as all this business is, at a point, it is, the story is, the world is, and there it all is, entified. It all starts at arm’s length, points here are there falling into focus, coming together or separating and becoming distinct. The process is not all that unusual, it’s all happening under rather obvious intersubjective circumstances. What am I trying to say? Nothing, if you ask me. I’m an old man or his son writing an old man writing his son writing an old man. But none of this matters and it wouldn’t matter if it did matter.