PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (12 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

“It’s nice to see bands that came as a result of the early days here,” says Bryce. “The Weakerthans, Greg MacPherson,

Propagandhi. Those guys came out of here, and they’re doing really good. It’s satisfying to know that if it wasn’t for us doing these shows, playing punk rock . . .” There is a long pause. “I do think it mattered. This is such an isolated place. We eat our own. So it really matters what happens here.”

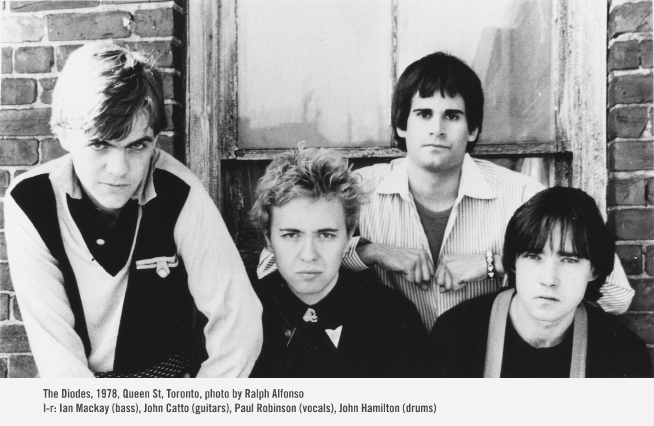

THE DIODES AND THE CRASH ‘N’ BURN

The Diodes [© Ralph Alfonso]

January 22, 1999, 5:30 p.m. EST

The Diodes are onstage together for the first time since 1980. The audience isn’t the cramped basement of their old local haunt, the Crash ’n’ Burn, and it’s not the packed crowds of their final American tour with U2. It’s the soundstage for

Open Mike with Mike Bullard

, a Canadian late-night talk show that tapes in the back of Wayne Gretzky’s Restaurant in the heart of Toronto’s theatre district (at 99 Blue Jays Way, natch). The band drives through the opening riff of “Tired of Waking Up Tired,” and their image will be broadcast across the country, doing for the band in three minutes what three years of driving back and forth from coast to coast couldn’t quite accomplish. The appearance, planned to promote a new best-of collection being released by the band’s former record label, is a reminder of the power of the Diodes, and of “Tired of Waking Up Tired.” In another life, it’s a song that would be a new generation’s “Four Strong Winds” or “Acadian Driftwood.” And for tonight, with hundreds of thousands of people watching, it will be.

Standing where the Crash ’n’ Burn once was, you would have no idea how close a shitty Toronto basement came to touching the iconic greatness of legendary American punk clubs like CBGB and Mabuhay Gardens. Here at 15 Duncan Street, in the heart of what is now a neighbourhood full of chain stores and sleazy, overpriced dance clubs, a small community of like-minded kids came together in the summer of 1977, filled a bathtub with some ice and some beer, and created something previously unseen on Toronto’s muted cultural landscape. It might not have the cool-kid cachet of late ’60s Michigan or mid-’70s New York, but Toronto possessed a thriving, self-supported punk scene that the Diodes, along with their manager Ralph Alfonso, helped to nurture with the help of a few friends and some unnaturally understanding landlords.

On September 24, 1976, the Ramones played their first show in Toronto at the New Yorker Theatre. “It was like the legendary story of how they came into a town and everyone who saw their show started a band,” says Ralph Alfonso, the Diodes’ close friend and future manager. “And it’s true.” As the explosive growth of punk in Toronto that followed demonstrates, those classic rock and roll clichés are always based on a kernel of truth.

“The first punk show I saw was the Ramones at the New Yorker,” says Diodes vocalist Paul Robinson. “I think everyone who started a band was there.” John Catto, the Diodes’ guitarist, reiterates, “That gig was important to everyone.” Along with the rest of Toronto’s fringe youth, Catto and Robinson left the New Yorker on Yonge Street that fall night with a completely flipped understanding of what a band could be and the desire to engage with a new cultural revolution.

Toronto in the 1970s couldn’t have been less like the grimy, exciting metropolis of New York City, or the glitzy, scary sprawl of Los Angeles. Most of Toronto was still a flat, cultureless bastion of Victorian morality, known as “Toronto the Good” and ruled by prohibition-era liquor laws. Which is to say that, beyond a few bars scattered throughout the downtown core, there was no nightlife. No patios. No club district. And no fun. As a result, Toronto’s first few punks all seemed to emerge from the already-alternative media labs and classrooms of the Ontario College of Art and the closest bar, Queen Street’s Beverley Tavern.

John Catto and Paul Robinson, both university students, had initially met at a party, their mutual enthusiasm for the original music emerging from New York drawing them together. The pair also made fast and fortunate friends with fellow punk and OCA student council president John Armstrong. Armstrong, later of the Concordes, had seen the Talking Heads at their first Toronto show when the band had only a few demos to their name, and, as student council president, he offered to bring them back to Toronto for a show at a small gallery the following January.

“The Diodes weren’t really a band yet. They were just some jam band that played in the basement of OCA somewhere,” says Alfonso. “Their whole purpose of being was to open for the Talking Heads at OCA. That was the extent of their life as a band as they saw it.” Catto addresses the band’s intentions point-blank: “We booked the Talking Heads into OCA so we could open for them.” The band already had seven or eight original songs, and by all accounts their debut show went well enough for them to continue what they were doing. At this point consisting of Catto and Robinson, along with drummer Bent Rasmussen and bassist David Clarkson, the band made their first tentative steps to engage with the scant few musicians also writing original music in bar band–dominated Toronto. Their second show was billed as the “3-D Show,” featuring pre-punk innovators the Dishes and the Doncasters at another OCA gallery. The real trouble came in finding a willing venue when the time finally arrived to move things beyond the walls of the insular arts college scene.

“The next gig we did was at the Colonial Underground. That was a disaster which ended in a riot,” says Robinson, matter-of-factly. “We were downstairs in a place called the Colonial Tavern on Yonge Street. Long John Baldry was playing upstairs, and I think that what happened was that he was doing an acoustic set, and we were very loud downstairs. The bouncers came downstairs and asked us to turn down. We didn’t, and they pulled the plug, and the whole placedturned into mayhem, with bouncers hitting people in the head with pool cues. It was a mad, mad way to play your third gig. Pretty much every venue in Toronto from then on banned punk bands.” A few months later, two Colonial employees were charged with assault during a particularly rambunctious Teenage Head show.

Riots weren’t unique to Toronto, and venues across North America were frequently afraid of inviting the fans and potential police attention implied by hosting a punk show. While it became popular to claim that every show with a spat of violence ended in a “full-blown riot” (see: every chapter in this book), there were times when the violence associated with punk, whether in the Colonial Underground or the streets of Los Angeles, was a very real concern. The Diodes experienced both.

“We were playing with the Circle Jerks, and that broke up into a riot that actually made the wire services across the world,” says Robinson. “My parents read about it. It was really scary. They thought it was really odd.” The story starts typically — an exuberant crowd takes to the stage while the band is playing, and, defending their equipment, that band takes action.

“It had very little to do with us,” continues Robinson. “There were some really crazy people trying to get onstage and knock over our equipment, and John hit someone over the head with a guitar, then a bouncer threw some guy down the stairs, and then some more people tried to get to our equipment. The whole place exploded, and we just grabbed our stuff, loaded up our van, and got out of there. They ended up on a rampage, all these L.A. punks smashing every plate-glass window within a few blocks of the venue. It was crazy.”

While cities like Los Angeles and New York were lucky enough to have a few oddballs with a bar and an interest in supporting what they saw as a new, exciting creative movement, there wasn’t anyone or anywhere like that in Toronto, save for the New Yorker promoter team of Gary Topp and Gary Cormier (or, the Garys), who had brought the Ramones to town but had yet to take over the Horseshoe Tavern. “They didn’t book punk bands anywhere,” says Robinson. “Which is why we started our own club.”

“We had this big building on Duncan Street,” explains Bruce Eves, co-founder of the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication. “CEAC was on the top floor, and the two middle floors were rented out. The basement was vacant. The guys from the Diodes approached us and proposed this project, and we said, ‘Sure, go ahead.’” What started as a practice space quickly morphed into something much more in the minds of a few punks with nowhere to call their own; along with their manager Ralph Alfonso, the band started to dream a lot bigger.

“CEAC was this weird, radical arts group,” explains Catto. “Real cutting-edge performance art, early European kind of thing where people would go onstage and cut their fingers off. Really out there.” The band had initially teamed up with the group through Catto and his studies at OCA, with the Diodes acting as musical accompaniment for spoken word performance art, hammering a few chords once a week in exchange for a free place to rehearse. “Then they went off to Europe for the summer, leaving us with the keys,” laughs Robinson. “We opened up this club without telling them.” Sneaking into lumber yards at night, the band built a primitive stage at the back of the room, erecting a bar using discarded doors and tracking down a bathtub to function as a beer fridge. When they got word that Californian power-pop trio the Nerves (the guys behind “Hanging on the Telephone,” later re-recorded and turned into an international superhit by Blondie) were in need of a Toronto date on their current North American tour, they got in touch with the band and put out the word that they would be hosting their first show. The Crash ’n’ Burn survived on a week-to-week basis using special events liquor permits for weddings and stag parties, and was born on that night in the summer of 1977.

“The beauty of it was that it was a social vortex for us. A place where like-minded people could get together,” says Alfonso. “It was barely a venue. It was a rec room. From the initial inner crowd of people that knew each other, you had new people coming in and making friends and expanding it and expanding it.” Now featuring longtime friend and former Zoom member John Hamilton on drums and Ian Mackay on bass, the Diodes were as solid as they had ever been, and after the first night with the Nerves and the Diodes, word quickly spread through the new (and very limited) punk touring circuit that the Crash ’n’ Burn was worth the trek to Toronto. The Dead Boys played two legendary nights in the building’s dank basement, and the Ramones showed up one night after their own gig just to take in a performance from the Diodes and fellow Toronto legends the Viletones.

“I saw the Dead Boys at the Crash ’n’ Burn that summer,” says Cleave Anderson, a founding member of Blue Rodeo and drummer for multiple first-wave Toronto punk bands including the Battered Wives, who once opened for Elvis Costello across Canada, and the vastly underrated Tyranna. “Stiv [Bators, the Dead Boys’ lead singer] was all over the place. They played one set. Ten songs, bang-bang-bang-bang. Fifteen to twenty minutes long. I guess they had to play two sets, and after standing around for not too long, they came back out and played the exact same set over again. The exact same set, top to bottom. I didn’t care. I loved those songs.”

Even with a more understanding behind-the-scenes team than the average Toronto watering hole, Alfonso, who acted as the venue’s de facto manager, didn’t always have the easiest time handling the clientele. “There was one night this guy who was on parole came down and smashed his way through the front door of the building, which is not the door you came in on,” he recalls. “You were supposed to come in through the side. And I was like, ‘Well, what did you do that for?’ And he’s like, ‘It’s punk man, hey!’ So I chased him all the way to the Rex [an old jazz club several blocks away] and got him arrested. I started to see all these hooligans coming out. People started thinking you could do whatever you wanted. I remember one night Goddo was there, smashing his glass on the floor, and I’m like, ‘What are you doing that for?!’ ‘It’s

punk

, man!’ And I go, ‘No, it’s not. Now I have to clean this up.’” Greg Godovitz, an icon of Canuck rock and roll in the ’70s and future classic rock radio host, wasn’t the only guy trashing the Crash ’n’ Burn when it wasn’t entirely necessary; a recurring character at the club — and future roadie for the Ugly — was a fellow by the name of Johnny Garbagecan, christened as such after making his first appearance at the venue by throwing a full trashcan into the room for no particular reason. “This one night, after we threw Johnny Garbagecan out, I’m upstairs counting the money and I hear someone just getting the shit beaten out of them,” say Alfonso. “And I’m like, ‘Wow, what the hell is going on?’ The next morning I go out, and there’s pieces of skin on the wall. It turns out Johnny had tried to pick up someone’s girl and just got the bejesus beaten out of him. There’s only so much you can do to scrape that off.”

Despite its importance to the local scene and growing popularity with New York punks, the Crash ’n’ Burn was winding down by the summer’s end, an unsustainable business undone by its own infamy. “CEAC’s income came from renting out the middle floor to the Liberal Party of Ontario,” Alfonso says. “These guys are pretty cool until you start coming in on Mondays and everything reeks of beer and there’s pee in the alley. I think the blood and skin might have been the last straw.” The band and its manager were, not surprisingly, politely asked to move along. While the loss of the Crash ’n’ Burn stung, its success had proved to bar owners in Toronto that punk could be viable, even when it was dangerous.

“I think it was a mistake to close it,” recalls CEAC’s Bruce Eves. “I know it’s hard to imagine what that neighbourhood was like 20 years ago, but there was nothing there. No SkyDome, no nightclubs, nothing. It was the only thing alive for blocks. No restaurants. No bars. Nothing. When they were doing the venue, it was real lively. When out of town bands came in, it was always really exciting. It was the first time a lot of the New York bands ever came outside of their city.” But the venue did open up new opportunities; in the same way that their west coast contemporaries would later benefit from their proximity to the Los Angeles scene, Toronto suddenly had an open invitation to visit punk’s ground zero, CBGB in New York City.

“I can remember standing outside the Crash ’n’ Burn discussing this while Teenage Head was playing,” laughs Catto. “Everyone headed down on a week’s notice — Teenage Head, the Viletones, the Curse, us, and the Dents. Most of us stayed around the corner from CBGB. Julia [Bourque] from the Curse had a friend who went to the Nova Scotia College of Art, who had a loft in New York. It was just a big floor. This open-plan loft, literally right around the corner from CBGB. Right in the middle of the Bowery.”