PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (10 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

“We turned to punk because we felt rejected by an increasingly conservative gay scene,” he says. “By the early ’80s, the gay scene was already unreceptive to punk.” In the late ’70s, it was a different story. Not just in Toronto, where some of the most important coupling between punk and gay culture happened, but in less celebrated cities like Victoria and Calgary. In fact, almost across the board, it seems like gay culture played a critical role in the development of punk in Canada. It’s a side note to the story of the Dishes and queercore, but it’s still vitally important. Punk was even more of an outsider here than in similarly small American cities like Minnesota or Seattle; in this way, a link was formed between two fringe cultures, neither of whom wanted to listen to Triumph or deal with bemulleted heshers.

The connection between punk and queer culture can be seen from coast to coast, and the cross-pollination of both scenes was stamped on the music and experiences of bands like the Dayglo Abortions. There is no doubt that Canadian punk would have been left struggling in the wilderness of our nation’s music community were it not for the interest and active support of the gay club owners, bookers, and restaurateurs of everywhere from Calgary to Halifax.

The Pointed Sticks played their very first show at a gay club in Vancouver. “It was at the Quadra Club,” recalls guitarist Bill Napier-Hemy. “It was a gay club, and the gay clubs were good about hosting punk. You didn’t have to jump through hoops. As a fringe community, they accepted us.” Nick Jones, the band’s vocalist, continues. “The rock rooms weren’t going to let us anywhere near them, nor did we want to be anywhere near them,” he says. “But the gay clubs were always happy to have us.”

In Winnipeg, Psychiatrists member Glen Meadmore, part of the holy trinity of the city’s first punk wave, consistently imbued his onstage persona with what vital ’90s Illinois punk promotion crew Chicago Homocore calls his “gay Christian punk” identity. Meadmore’s ongoing musical career would include collaborations with artists ranging from Pyle’s Shadowy Men to gender-bending exploratory musical artist Genesis P-Orridge.

Moe Berg of Edmonton’s Modern Minds recalls numerous shows taking place at a local leather bar. “It was a really tough cowboy bar,” he says. “Full of guys who looked like they could kill you. Just no girls, and all gay guys.”

Even in Hamilton, a working class rock ’n’ roll town, the Forgotten Rebels’ Chris Houston speaks of the importance of outsiders sticking together and the influence of the music scene on his own worldview. “Punk rock is all about tolerance,” he says. “We’re all characters, whether you’re some weirdo or you’re gay or whatever, we stick together. I think that tolerance is something people who live outside the box really need. It was very special to me when I think about the cast of characters I met.” Similarly, Calgary, another town often considered a hotbed of Canuck conservatism, possessed a thriving gay scene that eagerly embraced the new punk movement. “There’s a big gay scene in Calgary, which a lot of people are unaware of since it’s a cowboy town,” says the Hot Nasties’ Warren Kinsella. “There was a kinship there. A common theme was that we were all outsiders.”

Art Bergmann recalls the halcyon days of Vancouver punk as being when there was the most cross-pollination between all the different fringe arts communities. “We had art bands, and artists playing guitars, and mixing with the gay scene and the punk scene,” he says. “And it all mixed together into this great amalgam.”

Until it was destroyed by a fire on New Year’s Eve, David’s was one of the only clubs in Toronto to allow punk bands the opportunity to play. “The gay stuff started after we would play,” says Cleave Anderson, drummer for a grocery list of first-wave punk bands and a founding member of Blue Rodeo. “Things got going there around eight or nine, and went until 11. Then the stage would be cleared, and the glitzy gay crowd would come in. You’d hang out for a while and get a flavour of something different.” Even drugs in Toronto were spun off from the gay club scene; amyl nitrite, or poppers, were a popular fixture of early shows at the Colonial Underground, a direct influence of the gay scene on early punk.

In Halifax, where the local American Federation of Musicians controlled all the live venues, save for an old hippie cafe on Grafton Street, a local gay bar was literally

the only other venue that would let punk bands play. “It was

all connected,” says James Cowan of Nobody’s Heroes, one of the city’s lone first-wave bands. “The alternative scene found a natural home with the gay scene in Halifax. It was all part of this below-the-surface underworld there. It was quite interesting.”

Even the endlessly shit-disturbing and politically incorrect Dayglo Abortions enjoyed a great relationship with the gay bar at the end of the street they lived on in Victoria. “The gays and the punks were both fringe groups that had been alienated from society,” says vocalist and guitarist Murray Acton. “And for the old gay guys, I’m sure nothing was better than a bunch of young punks getting sweaty and pushing themselves around onstage.” He then tells me one the most wonderfully weird stories I’ve ever heard, about the band’s drummer Bonehead, and his gay roommate, Steve, who tended bar down the street. The pair shared a tiny bachelor apartment separated down the middle by a sleeping bag hung from the ceiling. (Mom, stop reading here.) “One night, we were hanging out at Bonehead’s apartment,” he says, pausing to make sure my mom is no longer reading the book. “We heard Steve come home from the bar with someone, and 15 or 20 minutes later, this guy rolls into the kitchen with a mailbag over his head, hogtied, buck naked, and we had to tell him he made a wrong turn and roll him back through the sleeping bag. We went back to what we were doing.

“The next day, I see Steve, and he tells me this story: ‘Two or three times a week, this cop comes in to make sure there’s no underage drinking in the bar. Monday night, he comes in and I see he’s got this rookie with him. He introduces the rookie and says he’ll be doing the beat now. Wednesday night, just the rookie comes back. Friday night, the rookie comes back, but not in uniform. He sits down at the bar and starts drinking. So I get the guy wasted and bring him back to the apartment. I get him all hogtied, with the mailbag locked around his neck. And I’m thinking about the time I got put in the hospital by the police in Regina. I got the shit kicked out of me. I lost a kidney. And I got this big Bowie knife on my dresser. And I was thinking about just slicing his throat. But I changed my mind.’ And he shows me his wrist, and he’s got poop around his wrist. He’s the only man I know who’s fist-fucked a cop. I thought, ‘Wow, what a guy!’ He’s been my hero ever since then.” He pauses, laughing. “They were a good bunch of people down there.”

But I digress. The point is Toronto wasn’t alone in forging a bond between punk and gay culture. The difference is the nature of the relationship; in other parts of the country, it appears to have been one of sympathetic tolerance, a recognition by the local gay community that punks were just another marginalized and occasionally persecuted group. In Toronto, the relationship was deeper and more symbiotic; punk might not have ceased to exist without the involvement of groups like General Idea, but punk flourished because of it. It gave the city a unique edge over places like New York, and while the measurable international benefits wouldn’t come until the mid-’80s with Jones, LaBruce, and queercore, groups like the Dishes sowed the seeds of a cross-pollinated punk and gay lifestyle that would put Toronto at the forefront of an important punk subgenre in the following decade.

The Dishes’ contributions to the city were obviously bigger than their bedroom politics. The band’s drummer, Steven Davey, was consistently active, co-writing songs with other Toronto bands when not busy scheming with the Dishes. Ball’s job at Peter Pan not only made for an ideal photo-op — “Look, it’s me, with all these dishes, and I’m singing for the Dishes!” — it started him down a path of restaurant and club ownership that would see him helm new-wave celebrity hotspot Fiesta Restaurant in Yorkville, establish the major lakeside club RPM (today the Guvernment/Kool Haus complex), and create club district staple the Whiskey Saigon.

By the end of 1978, the Dishes were broken up. They left behind two great EPs, compiled in 2002 on the

Kitschenette

best-of CD. Their cultural legacy would be lessened if the tunes weren’t there, but songs like “Hot Property” and “Chef’s Special” show a weird band at the top of their game, processing David Bowie through a lens that had been cracked and fucked up on the floor of the Crash ’n’ Burn during the summer of ’77, a time documented in the band’s own song, “Summer Reaction.” Combined with the grocery list of important Torontonian firsts that they accomplished during their short run, it’s hard to understand why there isn’t some weird, sexual statue dedicated to the Dishes in front of city hall on Queen Street.

But I guess it’s never too late.

WINNIPEG

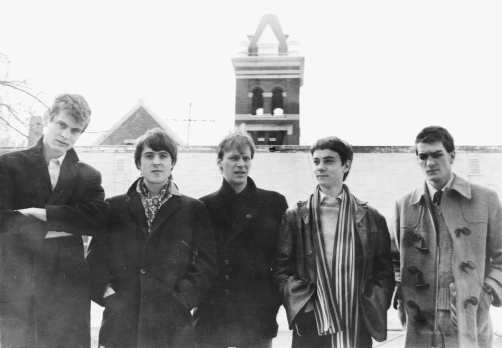

Popular Mechanix [courtesy of Greg Gardner]

April 3, 1979, 10:30 p.m. CST

Richard Duguay is sitting on the chest of the vocalist of his band, Lowlife, one hand around the guy’s throat, the other raised in a fist to beat his face in. He takes a breath. Lying around them are the unfolded sleeves for their first 7" single, “Leaders.” The band has been up late cutting and folding, whispering in drummer Mark Halldorson’s parents’ basement while they attempt to get the stupid thing ready for distribution at shows and local record stores. But tensions between the group are reaching a breaking point, and despite the thrill of being the first punk band in Winnipeg to record and press a single, when Duguay looks down at his friend, he knows the band is done.

It’s no small feat that Winnipeg produced the greatest Canadian punk band of all time. Sure, that’s a lofty statement, especially in the middle of a book about a lot of great punk bands. And I know art is supposed to be subjective. But unfortunately for all the other incredible bands that have crashed through Canada’s grey cultural fabric, it is an objective, measurable fact that Personality Crisis is the ultimate creation of our wide, icy tundra. In a crowded field of weirdos, they are the weirdest. They didn’t always look like punks, they didn’t always sound like punks, but they combined Winnipeg’s honest working-class tradition of hard-rock worship with the ultimate tough-guy weirdo vibe of early punk. They emulated no one and pooled the sounds of their city with the newly born genre of hardcore to create a truly original sound that, like many of the bands featured in these pages, couldn’t have come from anywhere else. They dressed in such an aggressively ugly fashion that their mere physical presence flaunted the rules and codes that had begun to form in punk circles, and they toured as hard — or harder — than any other Canadian band. They produced one full-length,

Creatures for Awhile

, that unfortunately wouldn’t see the (dim) light of (record stores) day until late 1983.

I originally hoped to dedicate a full chapter to them, but the more I came to understand the era I was attempting to capture, the more I realized they fell outside of it. If I wasn’t going to include great second-wave bands like Young Lions in Toronto, or the Nils in Montreal, or Jellyfishbabies in Halifax, I would be breaking my own rules to include a band whose primary contribution came long after the first wave had crashed over the Grain Exchange in downtown Winnipeg. So, this isn’t the story of Personality Crisis. But it is the story of the creation of a scene that helped coax such a gorgeously deformed beast into being. It is also a recommendation to buy a copy of Chris Walter’s exhaustive and incredible Personality Crisis biography

Warm Beer & Wild Times

, order yourself a copy of the recently reissued

Creatures

LP, and pay attention to how Winnipeg, the coldest city in the world with a population of over 600,000, created as vibrant a punk scene as one on the Californian shores of the Pacific Ocean.

“There were always new people,” says Greg Gardner, drummer for Popular Mechanix. “Someone’s younger brother or sister had grown up, and they were coming out to shows.” Gardner and Pop Mex were the ever-touring bridge between the bar band scene of the ’70s and the new sounds of punk emerging at the end of the decade. Popular Mechanix had been gigging regularly around Winnipeg since 1975, but it only took a few years for them to understand that it would take more than a few monthly spots at a hotel bar to break their band. Like their sonic forefathers and generations to come, Gardner and the rest of the band got in the van and lit out for the coast, returning only to pick up a few belongings to sell in order to keep them on the road as they headed out for Toronto. It was a process they repeated, each time returning to a slightly different-looking scene in their hometown. And then, in November 1978, Winnipeg punk finally had its official coming out party.

“My brother and I paid a buck each for three bands at the University of Manitoba,” says author Chris Walter. Walter, whose gritty prose has helped define the punk fiction aesthetic, was one of the few attendees at the first official punk concert in Winnipeg. “The bands were noisy, they were terrible, they didn’t know how to play, and the sound was the shits. But it was great. It was something completely new, especially for Winnipeg. It was

brand new

, and you had this feeling that history was being made, you know?”

Those three bands — Lowlife, Discharge, and the Psychiatrists — formed the foundation of Winnipeg’s nascent punk scene. They did make history. So while their names don’t ring out beyond the site of the old Spud Club and the Arthur Street Gallery, they played a crucial role in the development of an original music scene in a city that, like the rest of the country, was a bastion of bar-rock and cover bands, allergic to anything unknown or unproven. Along with Popular Mechanix, these three bands paved the way for an inventive hardcore scene that became one of the best in North America, forging a Canadian proving ground for some of the midwest’s most important post-punk acts like Hüsker Dü and Soul Asylum. The first wave of punk may have arrived a few years late in Winnipeg, but that didn’t stop bands from creating a genuinely viable scene that set the stage for some

seriously

vital shit in the 1980s. And it can all be traced back to one show at the University of Manitoba.

“It was amazing to be on a big stage, but I’m sure we were awful,” laughs Colin Bryce, who played guitar and sang in Discharge. The band never recorded, so it’s hard to tell if Bryce is a modest guy, or just really honest. Technically speaking, Discharge started in 1975, a bunch of 14-year-olds covering their favourite songs by the Who and the Kinks. “Back then, you had to play because no one was playing what you wanted to hear,” Bryce says. “We would go see mainstream rock bands just to be around music. But there was nothing we actually liked.” At the same time, Bryce began to notice the new sounds of bands like the New York Dolls and the Stooges, and by the time ’78 rolled around, Discharge was a full-fledged punk band, one-third of Winnipeg’s first-wave scene.

“Discharge could actually play,” says Richard Duguay, whose first band, Lowlife, shared the stage with Bryce at the U of M gig. “They were quite good. You could tell they had been playing for a few years.” Discharge had a measurable influence on the other almost-punks in the city; speaking with members of the hardcore community that sprung up quickly after the crest of the city’s first wave, the band is clearly a respected entity. In discussing their small but important legacy, Bryce reveals that a one-time Winnipegger David Tudor, a British native, wrote a book in the ’80s that transposed his experiences in the early ’Peg scene into an English setting. Long out of print, the book is called

Swank

, and some internet-sleuthing turned up a few used hardcover copies floating around the world, one of which I ordered for 99 cents, plus five dollars shipping.

By the time the book showed up, I had completely forgotten why I had ordered it. It came in a package with Greg Godovitz’ autobiography,

Travels with My Amp

. The Goddo bassist’s memoir, a tale of the band’s Canadian rock and roll excess just before punk showed up and ruined the party, made some sense; he was a fixture in the early Toronto scene, albeit a curmudgeonly, out of place one. But

Swank

was, to my eye, a novel, set in England, written by someone whose name I had never heard. I checked my notes; I had never interviewed a David Tudor. I scanned the pages for a reference to Canada, to any band whose story I was following. Nothing. At various times during the completion of this project, I have come dangerously close to completely losing my mind. When I feel as if I’m really in the good shit, truly grasping the precise nature of the story I’m trying to tell, I won’t sleep. Fuelled by an endless drip of cheap coffee, I will work until I am no longer able to sit upright at my kitchen table. And around then, I’ll begin ordering things off the internet, under the assumption that my brain, which must be functional for research and writing purposes, does not need to be active for the procurement of reference material. This dream-like state generally ends with the eventual arrival of sensible books and movies at my door.

Swank

was not sensible.

Transcribing Bryce’s interview a few weeks after its mysterious appearance, I was immensely relieved to hear the sudden explanation of its presence. And then impressed at myself for ordering such an obscure piece of ’80s English literature. “That book is all about his time in Winnipeg,” says Bryce. “And his experience hanging out with us, at practices and going to shows. It’s an interesting insight into what happened here.” The book paints a bleak, nihilistic portrait of early punks, but between the intense violence (someone stabbed in the face and throat with scissors!), there are detailed and, based on my interviews, pretty accurate depictions of early punk shows, poorly attended and poorly played. While not quite a roman à clef of the Winnipeg scene, ultimately, the book is a compelling vision of rebellious youth striking out at dominant culture, and then looking for a place inside of it.

In it, a band called Snuff Flix, modelled after Bryce and Discharge, plays a show at a small community hall. Tudor’s description of the show matches the popular opinion of the early U of M gig: “The sound was astonishing. Its very crudity inspired awe.” Snuff Flix barely finish two songs before storming offstage, applauded by their fanbase of a half-dozen friends. Later, the band performs with a pub rock–era new-wave group called Captain Flash and the Instamatics. The band had all the credit and notoriety for being the most interesting local band of their time, but when punk rock exploded, all their younger fans formed bands, leaving Cap Flash feeling like a “half-accepted, half-tolerated anachronism.” The description rings with the same dismissive tone used by some of the hardcore-era punks I spoke to about Popular Mechanix, a band that never quite fit with the new fashion of punk. Pop Mex had been too left-field during the reign of The Bar Band, and when punk ushered in a new breed of stripped-down rock and roll, they were too pro to kick it with the kids. Bryce’s own musical proficiency and frustrations with the increased uniformity of the punk scene eventually led him down a stranger musical road, as well.

“I wanted to do something that was more funky,” says Bryce. “I was into R&B and soul, along with the punk stuff.” The result was Dub Rifles, a genre-busting mix of Stax and Sire Records featuring a full horn section along with the traditional guitar, bass, and drums. The band didn’t record until 1982, and the resulting EP,

No Town, No Country

is extremely difficult to track down. When I finally found a copy, I was truly impressed. Its mix of disparate elements wouldn’t have been out of place on

Sandinista!

or

Armed Forces

, and it speaks to the genuine breadth of Bryce’s musical vision, however unappreciated it was at the time.

“We required a little wider taste, and we found it hard to fit into that scene,” he says. “Plus, we did a lot of drugs.”

Like Dub Rifles, Popular Mechanix often found themselves outside of the punk scene, despite their integral role in opening Winnipeg up to original music that didn’t involve a blues scale. Most of their songs have been lost to time, despite producing two full-length records in the late ’70s and early ’80s and gaining some high-profile fans in Southern Ontario. By all accounts, though, those records, with thin production and emphasis on dated keyboard sounds and effects, don’t even come close to capturing the energy and power of the band’s live show. And really, it’s no surprise that they had trouble finding an engineer familiar with their sonic references in 1979 Winnipeg.

“The engineers kept saying, ‘Do you do anything slower?’” say Pop Mex drummer Greg Gardner. “We had to say, ‘No, don’t worry, this is how it’s supposed to sound.’ I think they were just happy to have a band in their studio giving them some business, even if we were definitely a little weirder than people were used to. They were recording stuff that sounded like the Eagles, folk music. And suddenly you have this fast music with crazy lyrics to contend with.”

The results, a self-titled record and its follow-up,

Western World

, both show promise, with a sound that occasionally comes off like a more kitsch incarnation of the Police’s debut

Outlandos d’Amour

. When the songs hit, though, they most definitely indicate a band that was at the top of their songwriting game, honed by years on the road between Vancouver and the Maritimes, trying to make ends meet as a full-time band, despite the endless financial roadblocks.

“It was not at all glorious. It was not at all comfortable,” says Gardner. “You’re making phone calls along the way to see if you can find somewhere to stay, you’re trying to figure out how to pay for gas. But for some reason, because of your age, because of the thrill of it, it didn’t bother us.” Early in the ’80s, the band even attempted to move themselves to Toronto, ultimately finding the bigger city just as impossible to survive in as their hometown. While they earned the respect of local heroes Teenage Head, who invited the band to open for them for a few days in Southern Ontario, they continued to have trouble getting regular gigs in a city where they were perpetually viewed as outsiders, as “The Winnipeg Guys.”

“We all had girlfriends who were helping us pay the rent, so we were lucky with that,” says Gardner. “In Winnipeg, you could get by. It was harder in Toronto. At one point, Stu and I both flew back to Winnipeg. I grabbed a box of records, he grabbed a box of comics, and we flew back to Toronto and sold them all. We made enough money to live for another couple of months.” When their comics money ran out, they headed home. “We just didn’t know how to make enough money to put the album out and tour. When we came back from Toronto, we had 17 cents between us after we filled up with gas. That’s how broke we were. We carried on for another year or so.”

Despite their earnest attempts at turning their new wave hobby into a viable career, they never took themselves too seriously — another important part of their local legacy. They still treated the business of being in a band like a genuine art, an approach that continued with Bryce and Discharge, a band that would closely align themselves with Winnipeg’s avant-garde art community. Gardner remembers one particularly weird performance — one that’s hard to imagine any serious band attempting today.