PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (25 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

“I had dropped off a tape of my band for the Garys, because the Edge was the coolest venue in town, and we wanted to play,” says Dave Bidini, whose band, the Rheostatics, had their very first live performance booked by the Garys in February 1980. “I was sitting in the New Yorker Theatre, and this guy said, ‘Are you Dave Bidini?’ It turned out that on the subway ride down, Gary Topp had called my house. My mom told him I was going to see a film at the New Yorker. And he decided to come and meet me and tell me he was going to book us at the Edge.”

While it may be popular to use the Last Pogo, the Garys’ final punk concert at the Horseshoe, as the marker for the end of the first era of Toronto punk, it’s important to note that the Garys’ work in the city didn’t end there.

Today,

The Last Pogo

film is the best window that latecomers

have into a long-gone era of Toronto punk. Like an

important anthropological document, it invites the viewer

into a very different world, one that looks a little like ours,

but is populated by very different people. It leaves you feeling not unlike Charlton Heston in

Planet of the Apes

; it may have been Earth all along, but for a few minutes, you really feel as if you’ve landed on a hauntingly familiar feral planet.

I meet Colin Brunton in the middle of a busy shoot week for a kids’ show he’s currently producing for a national broadcaster. After we chat for a few minutes in his upstairs office, it’s obvious that he’s excited to show me something, and he makes his crew swear to secrecy.

“There’s nothing going on down there, right guys?” he asks.

“Nothing out of the ordinary, no,” replies an obedient production assistant.

“Good. Let’s go downstairs.”

As we walk from his office to the stairwell, the smell of manure, out of place in a suburban sound stage, becomes

stronger. When we get to the stairwell, there’s hay on the floor.

“You guys have a horse here today?”

“No. No horses.”

We turn the corner and I see a full-size African elephant lifting a child actor up onto its back. There’s a small crew standing around, taking videos on their phones, and Brunton is grinning from ear to ear. I’m just shocked to be so close to an elephant. It’s an unexpected left turn in my afternoon.

“Guess how much it costs to get this thing out here for the day?”

The number is huge. Knowing that the budget for this show can’t be that big, I ask how he’s afforded a full day of Dumbo antics. The answer is appropriately do-it-yourself: you juggle stuff around, and you make it work. Three decades later, Brunton’s ethic hasn’t changed.

The Last Pogo

was made on borrowed equipment and borrowed time. He made it work, and if he was stressed, it didn’t matter. Because it was fun. As he rushes off to tend to the day’s business, I can’t imagine it’s been easy to get this elephant here. But it sure was fun.

Many of Toronto’s first-wave bands may have stumbled around the time of the Last Pogo, but the Mods just ratcheted things up and hit the road. Teaming up with Teenage Head, another group of proper road warriors, the band struck out for the midwest and east coast, performing in cities like Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Detroit, a move that helped the bands build a substantial following stateside. Frequently, the Mods headlined over Teenage Head, who, despite their immense live power and popularity at home, continued to have difficulty breaking into the American market.

“It was a very, very isolated scene,” recalls Scott Marks. “Inside clubs you’d play, there were people who were into it. But to the rest of the world, it didn’t exist.” And when things didn’t go well, as they often didn’t when you’re a band spending as much time on the road as the Mods did, they went horribly. Bigger cities were generally good; in Detroit, a close relationship with new wave upstarts the Romantics helped the band win over crowds, and New York was always welcoming to Toronto bands. But touring Canada has always been difficult, and the need to fill in nights between bigger shows can lead to some uncomfortable mismatching between bars and bands. “The places you used to go to play would either have a scene, or not have a scene,” Marks says. “And if they didn’t have a scene, it was fucking horrible. We were booked to play in Cobourg, and we walked in there to soundcheck and knew it was going to be a horrible night. You can look at people and tell what they like, and everyone in the bar had on construction boots, blue jeans, lumberjack jackets, and long hair. They wanted to hear Zeppelin, Styx. We were a long way from that. It was impossible to get yourself up for the show, because you knew the reaction was going to be fucking brutal. Sure enough, we get up and do our first song, and there was no response. Not even a boo. Then we’d have some fun onstage and jam, and the bar owners would be pissed off. But there’s no point in playing our songs, because these guys didn’t want to hear it anyway.”

It wasn’t all apathetic heshers and jam sessions. As with any young band on the road, away from parents and responsibility, the Mods did their best to enjoy their freedom. “We were wrestling in our hotel room in Detroit, in one of these motor hotels with a big plate-glass window where you park outside your hotel room,” says Quinton-Steinberg. “One of our guys threw our roadie into the heavy drapery that was in front of this window, and it knocked the window out. The window crashed to the ground, and of course we were staying in the cheapest motel we could in the worst part of town. The owner came out with a shotgun and demanded money — cash — on the spot. So we ran to Teenage Head, who were staying in the same place, and cobbled together as much cash as we could so he wouldn’t call the police.”

It’s unsurprising that the Mods quickly grabbed the attention of a few labels, and perhaps equally unsurprising that this “success” set in motion their eventual implosion. The band’s first 45, recorded in November 1978, had cost $120. Now, they were looking for something bigger. Asked to produce demos for Warner Bros., the band whipped off a batch of songs in one night in the studio, some of which are included on their 1996 collection

Twenty 2 Months

. When the Warner deal never came through, the band opted to sign with a disc jockey named Keith Elshaw from local rock radio station Q107, whose indie imprint, Airwave Records, had just inked a distribution deal with CBS, home of fellow Torontonians the Diodes.

“We recorded the album with Elshaw, and during that time period, CBS approached us about signing directly,” says Marks. “Then the trouble began. Elshaw found out about it and started suing CBS for . . . what’s it called? Fucking around with someone’s contract, basically. CBS danced around for four or five months, then decided they wouldn’t sign us.” Around this time, things start to get muddled for the Mods. At some point, they changed their name to the News, after realizing that the Mod revival happening in England had rendered their name about as relevant as calling themselves “The Rock and Rolls.” While legal trouble between themselves, Elshaw, and CBS kept them sidelined, Quinton-Steinberg was made an offer he couldn’t refuse — playing drums with Youngstown, Ohio’s most infamous punk export, Dead Boys vocalist Stiv Bators.

A regular on the Toronto scene, Stiv had seen Quinton-Steinberg on one of his northbound trips to visit his girlfriend, Cynthia Ross of the B-Girls. “He was club-hopping when he was in Toronto in January ’79,” says Quinton-Steinberg. “He saw the Mods at the Cheetah Club and came up to me after the gig and was so drunk he could barely stand up. He said, ‘I’m doing a solo album in L.A. this summer, and I want you to come and play on the record.’ I said okay, and I never heard from him again. Six months go by, and I get a call from him. I had just graduated high school, and he said, ‘Do you remember when I talked to you?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but you were so drunk you could barely stand up.’” Bators had remembered the conversation and was dead serious about getting the young drummer out to Los Angeles. Within a few weeks, Quinton-Steinberg was on a plane to the west coast, and within hours of landing, found himself in Leon Russell’s studio, working on the material that would comprise Bators’ first solo album,

Disconnected

. Bators’ new girlfriend, former Playmate Bebe Buell, was hanging out a lot. Naturally, Quinton-Steinberg couldn’t have been a happier high school graduate. But he eventually had to make his way back to Toronto, hoping to pick things up with the Mods now that their legal troubles were coming to an end.

“Summer of ’79 was when things really gelled for us,” recalls Scott Marks. “We played in the States a lot that summer, and we came back to play a Monday or Tuesday night at Larry’s Hideaway in Toronto. We put some posters up, figuring it’s a weeknight, so whatever. We showed up at the club, and they were lined up to get in.”

Back on the road, the band was happily continuing their streak of youthful delinquent behaviour. “We were going to Montreal for the first time,” says Marks. “We had just crossed into Quebec and stopped to get some gas. I went to go take a leak, and I look down on the sink beside me and there’s a baggie with a bunch of vials of hash oil and these rolled up pieces of tinfoil. I had a pretty good idea what it was, so I grabbed it and stuffed it down my pants.”

“We’re all sitting, waiting in the car, and Scott comes out running,” says Quinton-Steinberg. “And he says, ‘Go.

Fast

.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Just

go

.’ He was in the washroom, and he found a bag full of drugs that had been, I guess, left for a drop off.”

“We get to Montreal, and we run into this bizarre character from Toronto somehow,” continues Marks. “We get to talking. He’s on methadone treatments because he’s a heroine addict. He’s got a litre bottle of bennies. So we gave him all this hash and stuff, and he gave us all these bennies. They were great because we were playing until two or three in the morning, and we needed all the energy. We were playing short sets to begin with and now we were playing them twice as fast. It was a fun trip.”

The trip wasn’t all fun, botched drug deals, and free Benzedrine, though. In Ottawa, Quinton-Steinberg ended up in the hospital when a bottle of beer was thrown at his head mid-song, knocking him unconscious. “Everything’s fine, the gig is going well, and some guy walks in off the street, picks up a full quart of beer, throws it at the stage, and walks out,” says Quinton-Steinberg. “He hit me right on top of the head, and I was out cold for a few minutes. We went to the hospital, and the police came. They said, ‘We know who this is.’ And I asked ‘How?’ and they said, ‘We have a description, the bartender knows who it is, blah blah blah.’ I asked if they were going to press charges, and they said I probably didn’t want to. It turns out he was a member of the Outlaws motorcycle gang.”

Back in the city, the band’s label woes continued. Stalled recording, broken promises from Elshaw, and the sight of their friends the Diodes being torn apart by the major label ringer started to cool Quinton-Steinberg and bassist Mark Dixon on keeping the band going. Despite commanding huge crowds and a sizable chunk of change for some big university shows, the Mods looked to be on their last legs.

“I looked at the Diodes as being a good sign. Like, ‘Shit, if they can . . . ,’ And what happens is that CBS signs the Diodes, and every other record label comes snooping around, doing demos with us . . . And then they decided not to do it. And that’s how the whole thing died on the grill. Rodney Bingenheimer was playing our record on KROQ, and we thought about going to Los Angeles. But it was impossible. L.A. was a world away and would have been way too much money for us. It would have been interesting if EMI had signed Teenage Head, Warner Bros. signed us, and we all went on to make records. Who knows what would have happened?”

Quinton-Steinberg would head back to L.A. to continue to play with Stiv Bators, who performed his infamous interstate car-surfing routine more than a few times during his stay. Despite the lingering “what ifs” of the band’s dissolution, there isn’t a hint of bitterness in either man’s tone, and their take on the Mods’ story is refreshingly modest. After all, it can be easy to reinvent your history after a few decades of snowballing interest and enthusiasm for anything related to punk’s first years in Toronto.

“Toronto had one of the best scenes. Toronto was way ahead,” says Marks. “But like it or not, Toronto bands were local and they stayed local.”

“None of us would have become rock stars,” laughs Quinton-Steinberg. “There’s no fucking chance. In those days, out of Canada, you had the Guess Who, Gordon Lightfoot, Anne Murray. That was about it.”

“Our last show was opening for Squeeze,” says Marks, who then quickly reconsiders. “No, that actually wasn’t our last show. Our last show was right after that, at some private school around Bathurst and Davenport. It was an all-boys school who were having their last year shebang. Some kids were fans of us, and they somehow talked their teachers into letting us play.”

It’s perhaps appropriate that the Mods, who were one of the few bands to try to reach outside of the confines of the Golden Horseshoe, still ended their career in the kind of adorably humble way that only a couple of well-meaning long-hairs from Scarborough could.

THE EXTROVERTS, THE IDOLS, AND SASKATCHEWAN’S FIRST WAVE

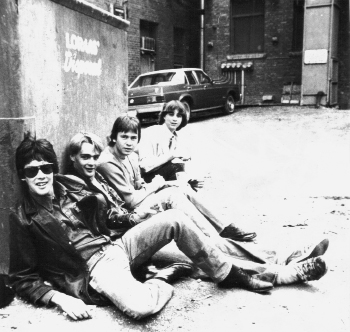

The Extroverts [courtesy of Les Holmlund]

January 15, 1980, 12:00 p.m. CST

“We’re fucking cancelling classes today!” Brent Caron, the Extroverts’ vocalist who, moments ago, was face-down in a pile of mannequins, is now screaming in the face of a concerned, flustered high school principal. A noon-hour concert at Campbell Collegiate, organized by students and billed, cutely, as “New Wave Day,” has gotten out of hand, and Caron’s suggestive mannequin pile-on was the last straw. With black and white TVs flickering away onstage (props that regularly perform double duty as a way for the band to covertly watch hockey games while they perform), the Extroverts have been told in no uncertain terms to stop. But Caron isn’t done, and after announcing the cancellation of the afternoon’s curricular activities, he offers one more valuable life lesson to the packed gymnasium: “This is the best form of birth control I know!” The band launches into “Giving Head, Getting Head.” They are promptly banned from performing at any high school in Regina ever again.

Many early punks reinvented themselves with new names, running the gamut from grotesque to comical. Shithead, Nazi Dog, Johnny Garbagecan. But Regina, a hard-working prairie city that is hardly a bastion of vulgar punk culture, somehow lucked into the most perfectly punk name with Pile o’ Bones, its original name until England’s Princess Louise offered up the less Ed Wood–esque “Regina” during a visit in 1882. The Pile was a very real pile of buffalo bones, assembled by local Cree and Métis who hunted in the area; it was believed that buffalo would not leave an area where the bones of their ancestors were kept.

Admittedly, this has little to do with the Regina of 1978 that birthed the province’s first punk band, the Extroverts. But, perhaps, some argument can be made for these teenage Ramones fans picking up on the primal, violent energy of their hometown and channelling it into jumpy, jangly songs like “Tactical Squad” and “Living in Poverty.” Maybe the city’s legacy as the site of the trial and execution of infamous Métis rebel Louis Riel informed their own cultural rebellion. Or maybe Pile o’ Bones is just a ridiculously cool name for a settlement.

The Extroverts started with a poster. Brent Caron, a student at the University of Regina, pinned up a notice that said he was looking for a band and cited influences like the Stooges, the Velvet Underground, and his latest discovery, a British band called the Sex Pistols. Not the most popular set of references in a city dominated by disco and bar-rock, just like the rest of the country. But just like the rest of the country, there were always a few other misfits with Ramones records stashed in between the sleeves of their T. Rex collection. In Regina, that guy was Les Holmlund.

“I felt inspired and empowered, even though I was a terrible guitar player. I had put up some notices and didn’t have any luck,” says Holmlund. “But I saw a poster at a university and found somebody else who was thinking along the same lines.” Holmlund called the number and agreed to meet Caron and the motley crew of recent high school graduates he had assembled under the moniker of the Extroverts. Unlike the cover bands that dominated the Regina bar scene at the time, the first thing the Extroverts did was learn a selection of songs written by Caron; fast, catchy songs informed by the new wave of hyper-melodic punk emerging from Britain. Barely show-ready, the band did the punk thing and booked a first gig anyway, playing in front of a thousand people at the University of Regina. Amongst those in the audience was Mike Burns, an aspiring manager and promoter who would soon become an integral part of both the Extroverts’ career and the rapid evolution of the city’s live music scene.

“It was part of a film night,” recalls Burns, who was running a screen-printing shop at the time. “Back in those days, there was no place to see any sort of alternative films in the city. So the student union put on films at the educational auditorium. They put on

The Rocky Horror Picture Show

and the Extroverts on Halloween. The band played before the movie, and they barely had a PA, just this little stage with a gigantic film space behind them. They had a couple lights at their feet, and they looked fantastic, 50 feet high in the shadow behind them on the film screen. It was great. People didn’t know what the hell was going on.”

“I remember looking out and seeing people who I knew were musicians and in other bands,” recalls Caron. “They were sort of weirded out with the whole thing because it was pretty rough and we were pretty tanked. We were as punk as we thought we could be with the limited amount of influence we’d had from the outside world.”

After opening for Brad, Janet, and Dr. Everett V. Scott, the Extroverts started down the usual road of parties and basements, performing songs whenever their peers would give them the chance. But when Mike Burns got involved as the band’s manager, things really started to happen, for the band and Pile o’ Bones itself.

“We tried to do shows,” says Burns. “The first couple were in front yards or in basements, that kind of thing. The classic kind of shows. But the Schnitzel House, that was something different.”

“Mike was working in a silk-screening place and next door to that was a restaurant called the Schnitzel House,” elaborates Holmlund. “Just a small restaurant, run by a really nice Hungarian couple. In the back, they had built a very small room that they had intended to rent out for wedding receptions and whatnot.” The Extroverts had different plans.

Burns booked the venue for a Monday night, and invited Vancouver punk legends D.O.A. to play. Billed as the Monday Night Pogo, it was the first punk show in a venue that still stands in Regina to this day. Bringing through bands like the Subhumans and Los Popularos, the Schnitzel House helped to create a centre for a burgeoning original music scene, becoming a destination for touring bands and a proving ground for new, original talent.

“I was always encouraging everything I could,” Burns says. That included a pint-sized teenager named Colin James, who would go on to become a major-label, Juno-winning blues rocker. “He had a band with some kids from town, but they were kind of beating around the bush on what they should call themselves. So I yelled to them, ‘You’re just a bunch of fucking wankers!’ And then I just posted the Wankers on the board outside,” he laughs. “They played a couple of shows. We just called them the Wankers.”

Shows at the Schnitzel House helped the Extroverts build up a substantial local fanbase as the city’s sole punk band. It helped that the band was writing original material at a feverish pace. Owing much to bands like Stiff Little Fingers and the Buzzcocks, the Extroverts’ songs were short and immediately catchy, heavily distorted (but hyper-melodic) guitars recalling a classic pop sensibility that tilted its hand toward a sloppier, more frenetic interpretation of the first Elvis Costello record. With Caron and Holmlund at the centre of the band’s songwriting, the pair churned out close to 80 original songs in their two-and-a-half year career, an impressive feat when stacked alongside other bands from the era who would frequently pad their sets by playing the same songs twice. Through vigorous practice and the precision that comes from regular high-profile opening slots, the Extroverts were also becoming a menacing live act, with Caron’s well-rehearsed sneer front and centre.

“Brent had a real magnetism,” says Burns. “He was quite dangerous. He was sort of like Frankie Venom [of Teenage Head]. But even more so. I always felt he was always on edge.” Later in our conversation, Holmlund refers to Caron as “a born frontman.”

“I’m definitely not the musician in the band, though. Les is,” defers Caron. “And he’s the leader. He comes up with the really catchy songs. We’re not great musicians. We’re not great at anything. But Les writes catchy songs.” The band’s songs, showmanship, and status as the city’s lone punk band eventually took them out of the back of the Schnitzel House and on the road to other cities in Saskatchewan, performing in the bars and pubs that had initially shunned them.

“When we played in a small town, generally we were playing music that people had not been exposed to yet,” says Holmlund. “It had its challenges.” While the band was going over well in the watering holes of their hometown, smaller Saskatchewan towns like Alida and Elrose would be a different story.

“We had things thrown at us, we had our vehicles sabotaged, and once, we got escorted out of town by the police,” laughs Holmlund. The cops were drawn to a particularly rancorous gig in Stoughton where the audience pelted the band with coins until they left the stage. The bar then called the police, who supervised the band’s speedy load-out to ensure they didn’t try to steal anything in the process. They were then driven to the edge of town and sent off into the Saskatchewan night. Similar scenarios played out across the prairies, like an eight-night stint in Brandon, Manitoba, at the Brandon Inn. It was quickly reduced to four nights and the band was unceremoniously fired.

Not every trek out of Regina ended in unmitigated disaster; a trip to Calgary for an intended week of shows at the run-down Calgarian Hotel turned into a full two weeks, and a trip to Saskatoon, a three-hour drive straight north, yielded the band’s only recordings. In a studio behind the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Training Academy, the band tracked songs like “Living in Poverty” and “Political Animals,” celebrating the sessions by spray-painting their band name on the side of the nearby cop shop.

Ultimately, raucous high school gigs and chances to open for the Subhumans weren’t enough to keep the band together, and by 1981, differing opinions on musical direction led to the end of the Extroverts, the first punk band from the previously culturally inhospitable province of Saskatchewan. Thankfully, the band was far from the last original band to emerge from the middle of Canada, igniting a spark of originality that continued through the decade.

“I saw the Extroverts at this outdoor thing for the Regina Exhibition,” recalls Jon Wyma, who would go on to play bass in pioneering Regina hardcore shit-kickers Diplomatic Immunity, sharing the stage with everyone from SNFU to Dead Kennedys. “I remember just being a little punker and all these older punks thought it was so cute that someone who was 12 or 13 was into the same music as them. I don’t think they even realized at that time, kids four or five years older than us, that there was another undercurrent of even more aggressive, more rebellious music coming along. But the Extroverts were definitely an inspiration in terms of knowing that you didn’t have to be Van Halen to play music. You could just be ordinary kids.”

And the Schnitzel House, that punk bastion of family-owned Hungarian entrepreneurial spirit, still hosts concerts every night of the week. It may go by the more club-like name of “The Distrikt,” but it’s a lasting reminder of the pioneering work of a few hockey-obsessed anglophiles and a pile of mannequins.

Only a year after the formation of the Extroverts and three hours to the north of their beloved Schnitzel House, Saskatoon’s music community was ready for the kind of sea change that punk was bringing to everywhere else in the world. The

lynchpin for an explosion of exciting, original music in the small prairie city of Saskatoon was found somewhere in

the shelves of a record store on Second Avenue.

Toronto transplant Ron Spizziri bought the failing Records on Wheels at the corner of Second and 21st, after specifically instructing the former owners to run down the stock as much as possible before he took control of the business. He set about building his own perfect store, one that would stock the new sounds of New York and London alongside the Anne Murray and Kenny Rogers records he knew would ultimately keep the store afloat. Says Spizziri, “A kid would come in, buying his punk albums, but he’d notice we were carrying things that he wanted to pick up as a Christmas present for his mom and dad.” Fuelled by gift-giving and and the timelessness of Kenny Rogers’ historically sound poker advice, Spizziri’s new Records on Wheels flourished in downtown Saskatoon.

“He was the guru about all the cool music from across the pond,” explains Jay Semko, bassist for the city’s first punk band, the Idols. “He had a line on what was happening in Britain, so you’d go and hang out with Ron and eventually spend money buying import records from him. It was a group of people I got to know. Before I got to them, I was playing in a bunch of different cover bands.” Spizziri’s influence didn’t end at the store’s cash register; invited by some friends to play a few records on their college radio show, he quickly landed a gig hosting his own program. A vital resource for new music, the late-night show on CJUS, broadcasting out of the basement of the University of Saskatoon’s Memorial Union building, allowed Spizziri a chance to promote new records in the store, upcoming gigs, and local talent, which was quickly developing in between the racks of Records on Wheels.

Jay Semko, later of platinum-selling Virgin Records roots-

rockers the Northern Pikes, formed the Idols in 1979. The band, who wore matching $25 double-breasted two-piece suits, played their first show at the university opening up for Canadian prog-rock outfit FM (the original home of legendarily mysterious performer Nash the Slash) and were almost immediately picked up by a local booking agent who saw an opportunity to market the band as “Saskatoon’s first new-wave band,” an attempt to capitalize on punk curiosity stirred up by media coverage of bands like the Sex Pistols

and the exploding international popularity of the new genre.

“He helped to build us, but we always thought it was really cheesy and hated it,” laughs Semko, who still calls Saskatoon home. “I just always thought billing us as that was kind of hilarious.” With a dearth of local punk gigs to play, the Idols were sent on the road in an old school bus, playing a mix of originals and Ramones covers, and spreading the punk gospel to Saskatchewanians who were

not

looking to convert.

“We were really freakish to them. We had short hair, and we all wore the same suits, and we played a bunch of songs they didn’t know,” recalls Semko. “Sometimes they just hated us. Like loathing. Real hatred.” One early show ended with an audience member approaching the stage and making a noose out of a microphone cable. The band continued to antagonize the audience by playing their fastest, hardest material, and before long, they were being chased out of town by 10 trucks full of rednecks. “They were following us, throwing beer bottles at the van and yelling,” says Semko. “You feel like you’re going to get tarred and feathered. We got 10 miles out of town before they gave up following us and harassing us.” The band’s first guitar player promptly quit.