PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk (21 page)

Read PERFECT YOUTH: The Birth of Canadian Punk Online

Authors: Sam Sutherland

THE FORGOTTEN REBELS

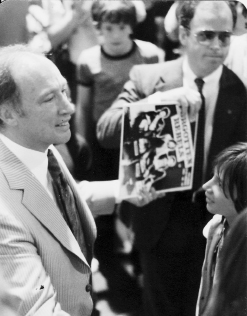

Pierre Trudeau with a Forgotten Rebels LP [© Stephen Burman]

July 19, 1980, 1:30 p.m. EST

Pierre Elliott Trudeau walks through a crowd of supporters in industrial Hamilton, confused by an incessant young woman who continually tries to thrust a 12” EP in his face every chance she gets. It’s a sunny summer day, but things have already gone weirder than expected; the Hamilton-area Liberal Party treasurer allowed the Forgotten Rebels, a band managed by his son, to play the event. They had promised not to play the tongue-in-cheek anti-government revolutionary anthem of “National Unity,” but, naturally, they had opened with it. Organizers pulled the plug on the band mid-performance, and now they’re here wandering the event, pissed off that they brought all their gear to a Liberal Party fundraiser to play for all of 50 seconds. And now there’s this girl, endlessly pushing that thing at Trudeau. Finally, the Prime Minister relents, takes the record, and hands it to a member of his security detail. In the time between receiving and handing off the record, Stephen Burman, the Forgotten Rebels’ manager and son of the local Liberal Party treasurer, has managed to take a photo of Pierre Elliott Trudeau holding the band’s debut EP in such a way that it really looks like he’s just carrying it around. And so continues the Rebels’ strange, endless dance with mainstream media and culture.

Mickey DeSadist is currently pissing just outside of my 1989 camper van parked within view of a bar in his hometown of Hamilton, Ontario, that’s named after his band’s second album. We’ve retreated here thanks to the unseasonably cold spring air driving us off the bar’s patio, but the cut-and-paste signage for This Ain’t Hollywood

still shines through the trees.

“What’s it like to be sitting here, 30 years after that record came out, still talking about it within view of that bar?”

“It does tribute to everyone who ever played in the band,” he says. “It’s a tribute to everything that happened in Hamilton. This Ain’t Hollywood

.

. . and you know, this ain’t Hollywood. We’re sitting here, in a van, in the parking lot of Chris’ Kitchen Outlet. I come here all the time to get accessories for my kitchen.”

DeSadist laughs. He’s right. And I bet his kitchen is immaculate.

Mike Gerlecki knew he wanted to play music, but in the mid-’70s, he could tell that his vision wasn’t gelling with the musicians he was finding. Hamilton flourished as Canada’s industrial capital at the turn of the last century; at one point, over 60% of the country’s steel came from the city. Just one hour to the west of the bourgeois intellectualism of Toronto, Hamilton had a well-earned reputation as a hard-drinking rock ’n’ roll town, the stomping grounds for such seminal artists as Ronnie Hawkins and King Biscuit Boy. In the ’50 and ’60s, just as America began to experience the decline of homegrown industry, so, too, did Hamilton. The mighty Stelco, once the biggest employer in the city, was forced to declare bankruptcy, and an exploding downtown was stopped dead in its tracks. It was against this backdrop that Gerlecki found himself trying to teach a bunch of unemployed heshers how to play like the Stooges.

“I was jamming with some guys and wanted to start a band,” he says. “I had this sound in my mind, Mott the Hoople meets the Stooges, and they said, ‘That sound’s not going to do any good.’ I was trying to write songs like that because I was listening to those bands

so much

, and they just didn’t think it was good. So the second I heard ‘Anarchy in the U.K.,’ I quit the band.” Not only did Gerlecki abandon the non-believers; he reinvented himself as Mickey DeSadist, an homage to the punk personas adopted by his British heroes.

Walking through Hamilton one day, DeSadist heard some kids playing sloppily in their basement. He walked into the house, uninvited, and the first lineup of the Forgotten Rebels was born. It was a simpler time.

“I never found musicians that really understood what I wanted to do, but I did find guys that wanted to drink and party so much that they didn’t care what they played,” he says. Inspired by the new imported singles showing up every week at Star Records, DeSadist tried to hone in on the sound and attitude he wanted to convey. Star was an anomaly for a city Hamilton’s size; stocking punk records in the middle of downtown long before similar stores popped up in Vancouver or Toronto, it became the nerve centre of the city’s music community.

Hamilton was also ahead of the curve musically; hometown boys Teenage Head had been together since ’75, pre-dating the official worldwide coming out party of punk. They were The Real Deal, a stripped-down rock and roll band in the vein of the Ramones or the Dead Boys, and when DeSadist saw their first show at Westdale High School, it further galvanized him to get his shit together and get the Rebels off the ground. Serendipitously, a Toronto writer named Gary Pig Gold reached out to DeSadist around this time and invited his new band to open for Hamiltonian psych-rock weirdo pioneers Simply Saucer at the YWCA on Ottawa Street.

“They were kind of like Syd Barrett with Pink Floyd meets the Kinks,” says DeSadist. The description fits; Simply Saucer was too weird for the Hamilton bar crowd, and when punk hit, they were too weird for many of the punks. Their landmark LP,

Cyborgs Revisited

, was recorded by Bob and Daniel Lanois in 1975 but didn’t see the light of day until 1989, falling out of print for the better part of a decade before being reissued in 2003. The album is a dazzlingly adventurous near-forgotten piece of experimental proto-punk, its lo-fi sound only serving to highlight the creativity in its songwriting and production — it’s no surprise that Daniel Lanois would go on to a brilliant career as the producer of landmark albums by U2, Bob Dylan, and Neil Young.

Cyborgs

is frequently cited as one of the greatest Canadian records of all time, and it is doubtlessly deserving of any accolade you could throw at it.

Saucer might have been a little outside of the punk world, but their importance to the development of the city’s music scene can’t be understated; their house was a centre of musical experimentation through the ’70s, a place where they rehearsed daily, wrote an album a week, and performed for whoever was interested in stopping by. The advent of punk, if not ideally suited to their prog-leaning style, helped them put down stronger roots in the city and gave underage punks a work ethic and who-gives-a-fuck attitude to aspire to. And, at this immediate point in the story, an opening slot on a show guaranteed to be attended by at least a hundred people in downtown Hamilton.

“We overwhelmed the audience,” says DeSadist. “Even though we couldn’t play very well, it was overwhelming to the audience to have someone writing the kind of songs we were writing at that point. I mean, it was overwhelming to me. Even if we couldn’t play well, we were already becoming a great band.” It wasn’t just the band’s songs that were shocking; DeSadist burnt a Canadian flag onstage, destroyed everything in sight, and shattered a door. Gary Pig Gold received the bill weeks later from the venue, citing $400 in costs, broken down as such:

Cleaning — 5 people x 5 hours x 5 = $125

Replace Door (Memorial Room) = $200

Damage to Vegetables (Carrots and Lettuce) = $25

Damage to Ladies Washroom = $50

No one knows what the YWCA meant about carrots and lettuce, but the rest seemed fair enough. Not a bad list for a first gig. The Forgotten Rebels were off and running.

Like Toronto’s Viletones, a menacing method of delivery for Steven Leckie’s strange brand of punk performance art, the Forgotten Rebels were, in many ways, a single man’s vision masquerading as a complete band. DeSadist was the driving force and central figure, enduring countless lineup changes and continuing to write and perform as the Rebels over 30 years later. The band’s aesthetic — smart, catchy, too offensive to be believable — is a direct extension of Mickey himself, a sarcastic, intelligent guy with a distinct patter and a continuing need to push the boundaries of good taste. Ultimately, he’s just trying to make people laugh, and maybe make a political point or two.

This was apparent from day one, when the song “Reich ’N’ Roll” appeared on the band’s first demo. Its slow, catchy, chorus intones, over and over again, “I wanna be a Nazi,” and for the casual listener, the song could easily be interpreted as anti-Semitic. But for anyone following along, the third verse spells things out quite literally: “I only wrote this song / Just to screw up the press / You gotta be quite an idiot for believing this mess.” DeSadist was right, and the media immediately pounced on the band for their supposed racism. It was a stigma they initially invited under the time-honoured cliché of “all press is good press,” but the need for DeSadist to consistently explain himself eventually wore thin. He’s just a provocateur, and a silly one at that.

“I’m not a racist, I just watched

Sanford and Son

a lot,” he says, laughing. “My humour was based on that, and Abdullah Farouk. He was the manager of the Original Sheik, Ed Farhat. I got a lot of my inspiration from wrestling. Ernie Ladd was another huge influence.” As the list of damages from the band’s first show can attest, the Rebels were about showmanship and shock from day one, and DeSadist seems surprised that no one made the connection at the time. In fact, the Forgotten Rebels are part of a long line of punks who channelled wrestling theatrics into their music and performance.

“Even David Thomas, when he was doing Rocket from the Tombs, claims that his persona was taken from wrestling,” says Damian Abraham, vocalist for Polaris Music Prize–winning art-punks Fucked Up, and my go-to expert on all things related to the crossover of punk and wrestling. Abraham has built his own career around the kind of theatrics that DeSadist is describing, embodying not just the persona of classic wrestlers, but the physical aspects of performance as well. Abraham regularly juices, which is to say the guy tends to smash stuff into his forehead so that he bleeds all over himself. After years of razor blade and pint glass-induced damage, Abraham now sports the same scars as veteran wrestlers like Terry Funk and Abdullah the Butcher, making him the ideal candidate to explain the frequent intersection of performance culture that is punk and wrestling.

When I ask Abraham to elaborate on the connection DeSadist is citing, he rambles off a grocery list of punk and hardcore groups that have drawn influence from classic wrestling personalities. David Thomas of Rocket from the Tombs, a Cleveland-based proto-punk band active from ’74 to ’75, is an early example, as Thomas’ stage persona was imbued with the over-the-top dramatic flair of ’70s wrestlers. Similarly, the Dictators’ 1975 debut,

Go Girl Crazy!

, sports a cover shot of vocalist Handsome Dick Manitoba in full wrestling regalia; the band’s whole career is marked by references to and reverence for professional wrestling. The Forgotten Rebels are part of the same continuum, one that grew even stronger throughout the ’80s with wrestling-obsessed hardcore outfits like ANTiSEEN and the Stretch Marks from Winnipeg carrying the torch for legends like Invader One and Terry Funk through wrestling-themed songs, records, and stage personas.

DeSadist’s mix of wrestling and strong, original songwriting was enough to attract manager Stephen Burman, who had just returned from a trip to the U.K., ostensibly to visit family, but, basically, just to see the Clash.

“I told Mickey I’d seen all these bands,” Burman says. “We were hanging out at Tim Hortons. I guess I got into the city and I sat down for a coffee and we started talking. He was just totally thrilled with me having been there and everything. And then he showed me what was going on, what the scene was in Hamilton at the time.” Tim Hortons on Ottawa Street was like DeSadist’s CBGB. He was there almost every day, holding court, drinking double doubles, eating doughnuts. If you wanted to find him, you went to Tim Hortons. It doesn’t get much more spectacularly Hamiltonian than that.

The Forgotten Rebels’ lineup shifted again, just in time for Burman to insist that they record a demo, the 1978 cassette release

Burn the Flag

. The tape helped the band get their first shows in Toronto and gave them enough momentum to justify entering a proper studio to record their first full-length album. Unfortunately, they had no idea what they were doing and didn’t have enough money to pay someone to help guide them through the process. The result was an unreleasable mess that the band had to find a way to salvage. Someone suggested Bob Bryden, the new manager at Star Records. Credited as the producer of the band’s debut,

Tomorrow Belongs to Us

, Bryden is emphatic that his initial role with the band wasn’t quite so prestigious.

“It wasn’t so much a production job as a salvage job,” he says. Despite being left with a collection of botched tapes to remix and master in a way that would leave the end product listenable, at the very least, Bryden was enthusiastic about the job. A newcomer to the city, he had approached the punk scene, Star Records, and Hamilton, as an outsider, but was eager to get his hands dirty.

“I consider myself a ’60s person,” he says. “I was very idealistic, and I still am. I spent most of the ’70s wondering where the revolution went. I took the ’60s really seriously, and I was put off by the appearance of nihilism and negativity that went along with the punk explosion. At the same time, I was amazed and refreshed by the idea of ‘Let’s get back to the garage, the basement, and make some fun two-and-a-half minute songs again.’” Before making the move to Steeltown, Bryden was living in Toronto and floundering. His own musical efforts had wound down by the middle of the decade; he was jobless and feeling aimless and apathetic. On a whim, he went to visit an old friend who owned a few record stores, driving about an hour out of the city to the flagship store in Oshawa. When he walked in, his friend was on the phone, in the midst of a heated conversation and visibly exasperated.

“He put his hand over the mouthpiece and said, ‘Hey, Bob. You want to go to Hamilton? Like,

now

?’ I was floored. I had gone into Oshawa just to hang around for the day. And I said yes.” The next day, Bryden visited the Hamilton store, the infamous Star Records. Though it was managed by Paul Kobak, Bryden had been told in no uncertain terms that he was to wrest back control of the business. It seems that Kobak had gone the way of Mistah Kurtz, with Bryden left to steamboat his way up the 403 highway and go all Charles Marlow on everyone.