Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (10 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Plan of John Fitch's

Steam-Boat. Library of Congress

.

Fitch soon inaugurated a ferry business between Philadelphia and Camden, departing regularly from the Arch Street Landing. This was the world's first steam ferry service. He later began transporting passengers and freight between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey, as well as points south of Philadelphia. The

Steam-Boat

cruised almost three thousand miles in 1790 alone.

In all, John Fitch constructed four steamboats that demonstrated the feasibility of using steam for water locomotion. He received a U.S. patent for his invention on August 26, 1791. Yet while his boats were mechanically sound, Fitch was not able to rouse support for his new method of ship propulsion. He never attained riches and was rewarded with only ridicule for his work. Nevertheless, Fitch was the most important of the handful of men who built steam vessels before Robert Fulton introduced his

Clermont

.

Other inventors experimented on the Delaware River with applying steam to watercraft in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Oliver Evans (1755â1819) of Philadelphia invented a steam-driven amphibious dredge that he called the

Oruktor Amphibolos

(amphibious digger). In 1805, Evans floated it down the Schuylkill River, steamed it up the Delaware to the central waterfront and then drove it west on Market Street back to where he started.

The contraption was intended to clear away river mud that constantly accumulated between the city's docks, but it turned out to be inefficient for that purpose. Still, this was the first motorized vehicle in America and the world's second motorized carriage, as well as the first steam-powered land vehicle in the world. General Motors once credited the

Oruktor Amphibolos

as the forerunner of the modern automobile. It was also a distant ancestor of today's Ride the Ducks amphibious vehicles that take tourists around Philadelphia and then plunge into the Delaware for a cruise on the river.

P

ATENT

N

O

. 1

AND

F

IVE

-P

OINTED

S

TARS

Samuel Hopkins (1765â1840) was another local inventor associated with Arch Street near the Delaware. This Philadelphia Quaker was granted the very first patent under the Patent Act of the United States on July 31, 1790. Hopkins lived on the north side of Arch between Front and Second Streets.

Signed by President Washington and Secretary of State Jefferson, United States Patent No. 1 was for an improvement “in the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process.” Hopkins's patent was noteworthy not only because it was the first of its kind but also because it was vitally linked to the fledgling nation's economy. Potash, America's first industrial chemical, is an impure form of potassium carbonate.

One block farther west on Arch Street is the Betsy Ross House, the supposed home of another inventive person. Betsy Ross's role in sewing the nation's first flag is subject to dispute, but the skilled upholsterer most certainly contributed to the Stars and Stripes's design by changing its stars from six to five pointsâfive-pointed stars were easier to cut from cloth. At the very least, Ross represents the many artisan women of Philadelphia who ran businesses and supported their families during the colonial and federal periods.

F

ILBERT

S

TREET

S

TEPS

(T

RESSE

'

S

S

TAIRS

)

AND

C

LIFFORD

'

S

A

LLEY

The steps and lower alley of Old Ferry Alley must have been abandoned in the mid-1800s, as Abraham Ritter notes: “Passing a flight of steps to Water street (now closed), a little below, at No. 53 [North Front].”

The southernmost stepped alleyway on that block was located at 29 North Water. Initially called Tresse's Stairs, the stairway was installed by Thomas Tresse, a notable merchant with scores of mercantile enterprises in Philadelphia's early days.

These stairs and the alley leading to the river were later named Clifford's Alley, since they led to Clifford's Wharf on the Delaware. Ships left for Boston, Savannah and other coastal ports from this place. The alley and wharf were named after Thomas Clifford, whose business was at 29 North Water Street. He and his family were shipowners and importers of hardware from Liverpool.

A corner of Clifford's dock had collapsed into the Delaware in the early nineteenth century. Nicknamed “the broken wharf,” it became a convenient place for boys to go swimming. This was an early leisure activity done amid Philadelphia's busy working waterfront.

S

TEPHEN

G

IRARD

(

AND

H

IS

T

OWNHOUSE

)

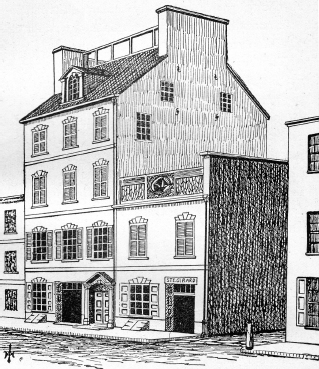

Bordering Clifford's Wharf were the wharves of sailor, shipping magnate and banker Stephen Girard (1750â1831). Other Girard properties surrounded his docks, including his home and attached office (i.e., “counting house”) at 23 North Water Street and his warehouse at 31 and/or 33 North Water Street. Girard was previously at 43 North Front, as Ritter records:

In 1791, and long before, No. 43

[North Front],

at the south corner of another flight of steps to Water street, our late opulent Stephen Girard, was proprietor of a greengrocery, where edibles to all tastes, from an onion to an apple and a bean to a slice of pork, could be had for the money. He occupied through to Water street, and could sell at No. 31 there as at No. 43 above

.

Stephen Girard resided at his Water Street town house overlooking the Delaware River for almost forty years. He lived with several young housekeepers, perhaps some of whom were mistresses, after he committed his wife to Pennsylvania Hospital in 1790. The daughter of a Philadelphia shipbuilder, Mary Lum (1758â1815) had suffered a debilitating mental illness after several years of marriage, causing her to be prone to emotional outbursts and fits of violence. She spent the rest of her life in the hospital's insanity ward. The situation caused Girard great sadness, since he professed to love her and especially since he never had an heir.

As a result, the French émigré focused his efforts on working and making money. At his house, he managed his investments and land acquisitions to accumulate a vast fortune. Here, he devised ways to use his money and personal credit to finance the War of 1812 for the United States. He entertained Talleyrand, Louis Philippe, Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon's brother and ex-king of Spain and Naples) and many distinguished French diplomats and refugees.

Girard and his servants could gaze south from the tall mansion's windows and rooftop balcony, searching for his cargo-laden vessels as they made their way up the Delaware from around the world to dock at his wharves. He owned some eighteen ships, and his packetsâships that sailed on a regular scheduleâwere the foremost line afloat at that time.

Girard spent much time at his mahogany desk, drinking imported wine and orchestrating his various commercial activities or reading the works of Voltaire, Diderot and Rousseau. He also contemplated ways to bequeath his money, including the founding of a school for “poor, white, male orphans,” and ways to improve his adopted city of Philadelphia.

Girard grew old and lonely at his waterside home, with only the wants of his business dealings to keep him occupied. Here, he passed away at age eighty-one the day after Christmas 1831, the richest man in Americaâhis estate was about $7.5 million. And here, his infamous thirty-five-page will was read for the first time to his relations and others while his body lay in repose in the parlor.

Drawing of Stephen Girard's house on Water Street.

From

The Life and Character of Stephen Girard of the City of Philadelphia

(1886)

.

Site of Stephen Girard's house today. The Philadelphia Anchorage of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge is in the background.

Photo by the author

.

The four-story house stood until the 1840s, when it was torn down and replaced with stores. The Delaware Expressway now covers the site completely. But incredibly, all of Stephen Girard's household possessions still exist. These itemsâfurniture, paintings, silver and textiles made in Philadelphia, England, France and Chinaâare on display inside Founder's Hall at Girard College.

N

ATHAN

T

ROTTER AND

F

RANK

W

INNE

Another importer/exporter who did very well in Philadelphia's river district was Nathan Trotter (1787â1853), born on Elfreth's Alley into a Quaker household. He lived and worked in this part of town all his life, plying his trade as a metals refiner and broker. Trotter grew rich and, like Girard, died a millionaire.

His firm, Nathan Trotter & Company, was headquartered at 36 North Front Street for over 150 years. His storehouse remains standing and is now a condominium. Still in business in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, Nathan Trotter & Co. is the oldest metals manufacturer and distributor in the United States.

That both Trotter and Girard became so moneyed while living a mere block from each other along the Delaware is remarkable. Other millionaires lived and labored on the Philadelphia waterfront; they will be profiled in subsequent chapters.

The one-time offices and warehouse of Frank W. Winne & Son are next to Trotter's building. Founded in Philadelphia in 1895, Winne was the nation's largest maker, importer and distributor of ropes, twines and packaging productsâall in high demand during Philadelphia's bygone mercantile period. The Winne buildings are now apartments, and the Winne company is still based in the Philadelphia area.

This block of Front Street most epitomizes the thoroughfare at the peak of its commercial and maritime importanceâat least the west side of the block. The east side has disappeared as a result of I-95. And, of course, comparable four- and five-story structures that once flanked both Water Street and Delaware Avenue are gone due to the highway.