Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (12 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

A postcard of the Piers at Penn's Landing.

Author's collection

.

Pier 3 was meant to be a condominium when the rehabilitation was planned, but the housing market collapsed and the building became an apartment house in 1986. Seven years later, a Miami developer bought the place from a foreclosing bank for $8 million. The 172 units at Pier 3 were turned into condos priced from $49,000 to $139,900. They sold out within three weeks in 1994. Meanwhile, after a similar story at Pier 5, 40 of 96 units ranging from $139,900 to $289,900 sold on a single weekend.

The notion of living by the Delaware River in Philadelphia had evidently become appealing by the 1990s. Nowadays, the Piers at Penn's Landing are successful condominium complexes. A few hardy souls even live year-round on boats at the marina between the two piers.

10

A

T

M

ARKET

(H

IGH

) S

TREET

B

EN

F

RANKLIN

, K

ING

T

AMANEND AND

C

HRIST

C

HURCH IN

O

LD

C

ITY

P

HILADELPHIA

Market Street is the eastâwest counterpart to Philadelphia's northâsouth Broad Street. The one-hundred-foot-wide avenue was originally named High Street, a term derived from one or both of the following: 1) “High” was the familiar name of the main street in most English towns, a custom dating back to Roman times; and 2) the street began at the highest point of the bluff that ran alongside the Delaware River when Philadelphia was founded. Writer Joseph Jackson confirms this in

Market Street, Philadelphia: The Most Historic Highway in America

(1918).

High/Market Street divided the Delaware waterfront into north and south. Piers and wharves were designated North and South depending on what side of the street they were on. Plus, for the longest time, the riverfront was characterized as being either the “North Wharves” or the “South Wharves.”

T

HE

L

ONDON

C

OFFEE

H

OUSE

Front and High was Philadelphia's first town center. The legendary London Coffee House, built in 1702, used to be on the southwest corner. Its position on Front Street (the Kingshighway) made the tavern a convenient stop for stagecoaches arriving from points north and south. The same goes for its proximity to the Delaware River. The London Coffee House became the most popular place in the city for both local and visiting members of the business and maritime communities to conduct business and discuss politics.

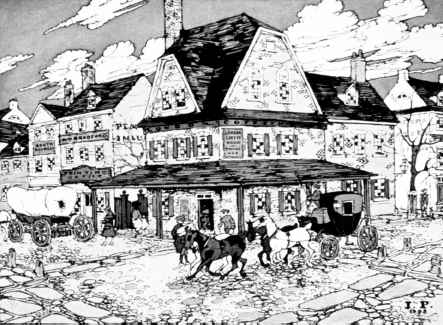

The London Coffee House at the southwest corner of Front and Market.

Library of Congress

.

The “Widow Roberts” ran the tavern for years, serving coffee, alcoholic beverages and simple meals. When she retired in 1754, printer/publisher William Bradford took over and turned it into the first stock exchange in America.

Over pots of piping hot coffee, owners of recently arrived schooners advertised their goods, investors bought and sold real estate, fishermen boasted about their latest catch, printers gathered the news, and public auctioneers sold a variety of merchandiseâas well as slaves. Revolutionary War pamphleteer Thomas Paine, boarding next door, was offended by the view of slave auctions from his window.

Philadelphia's businessmen informally established the Philadelphia Stock Exchange at the London Coffee House in 1790âpreceding the New York Stock Exchange by two years. Seeing the need for more substantial accommodations, they soon moved to City Tavern (aka Merchants' Coffee House) a few blocks away.

The London Coffee House became a general store in 1791 and then a tobacco shop and cigar manufactory. It gave way in 1883 to the five-story edifice that still stands at 100 Market Street. This building was later home to the Franklin Trust Company. As of 2011, it has been vacant for some thirty years, having last been a bar and grill, but it will soon open as a restaurant.

T

HE

H

IGH

S

TREET

W

HARF AND

B

EN

F

RANKLIN

The High Street Wharf was a bustling place early in the eighteenth century. This was where boats from Burlington came to the city, offering eighteenth-century travelers from upper New Jersey and points north the last part of their journey to Philadelphia.

One such traveler was Benjamin Franklin, who entered the city for the first time on October 6, 1723, as a dirty, tired and hungry runaway. He had come to Philadelphia, together with others, via a rowboat he helped paddle from Burlington. After leaving the wharf, he went straight to a bakery on High Street and purchased three cents' worth of bread, which turned out to be three large loaves, as the story goes.

T

HE

H

IGH

S

TREET

M

ARKET

S

HEDS

The High Street Wharf was also the main landing for boats that delivered produce grown in New Jersey. This went on for some two hundred years.

High Street began to be called Market Street about 1800 because this was where Philadelphia's first food market was based. Covered stalls were situated in the middle of the road starting at Front Street and gradually extended westward beyond Eighth Street. A crowded fish market occupied the middle of the street from Front Street to the Delaware River for decades.

The High Street Market Sheds came to rival the marketplaces of London and Paris. Farmers from the hinterlands of Philadelphia County would come into town on Wednesdays and Saturdays with their wagons of crops and meat. There, they joined farmers from the Garden State at what was sometimes called the “Jersey Market.” Monetary face-offs would occur at noon on market days when rivals tried to outbid one another during horse auctions.

What is often left out of history books is that the sheds of High/Market Street served as hunting grounds for the city's many prostitutes, who would prey on the naïve rural farmers who regularly came into Philadelphia to sell their harvests.

Indeed, the busiest precinct for streetwalkers was the city's waterfront in the eighteenth century and afterward. Dozens of ships docked at Philadelphia's wharves every day, filled with seafarers who had not seen a woman in weeks. The ladiesâoften the wives or widows of sailorsâtook their johns back to rented rooms at sordid inns along the alleys or courtyards near the docks.

Market Street's name was made official by an ordinance of 1858âironically, just a year before the archaic food stalls were ordered removed. All the market sheds were taken down about 1860. The bus shelter now at Front and Market was designed to look like a market stall.

T

HE

L

ENNI

-L

ENAPE AND

W

ILLIAM

P

ENN

(I

OF

II): C

HIEF

T

AMANEND AND

H

IS

S

TATUE

Across from the bus shelter stands an arresting statue of Chief Tamanend (ca. 1628âca. 1698), the principal Lenni-Lenape leader who welcomed William Penn upon his arrival to this region in 1682.

Tamanend (“the Affable One”) partnered with Penn (“Mikwon”) to bring about the bold accord in which Quaker settlers and local Native Americans would live together in peace. The chief consequently became a folk hero identified throughout the colonies as the “patron saint of America.” Beginning in Philadelphia, his memory was observed with festivals, and social groups known as the Sons of Saint Tammany sprang up during the War for Independence in opposition to the British-oriented societies of Saints George, Andrew and David. Tamanend was even nicknamed “King Tammany” as an insult to King George.

Crafted by artist Raymond Sandoval and dedicated in 1995, the

Tamanend Statue

was one of the first sculptures of a Native American in the United States. The chief stands on a turtle (representing Mother Earth) with an eagle (a messenger of the Great Spirit) on his shoulder. The eagle is grasping a wampum belt symbolizing the world-renowned “Treaty of Amity and Friendship” (discussed in

chapter thirteen

) between William Penn and Tamanend and his Indian colleagues.

The belt reads what Chief Tamanend reportedly announced during the 1683 treaty summit: that the Lenni-Lenape and the English colonists would “live in peace as long as the waters run in the rivers and creeks and as long as the stars and moon endure.”

There's talk of moving the statue to Penn Treaty Park, where the memorable convention took place. The park is covered in a later chapter.

R

IDGWAY

H

OUSE

H

OTEL AND

O

THER

D

ELAWARE

A

VENUE

H

OSTELRIES

The Ridgway House Hotel was once located at 1 Market Street, on the street's north side at Delaware Avenue. This lodge catered to visiting mariners, produce sellers and others who needed or wanted to be close to the commercial activity by the Delaware. The cheapest accommodations, for twenty-five cents a night, offered a common room with twelve beds.

The six-story building opened in 1838, about the time that Delaware Avenue was first laid out along the river. The owner was Jacob Ridgway, who also owned the Arch Street House at the foot of Arch Street.

An October 1897 newspaper article reported the suicide of a respected lawyer from West Chester, Pennsylvania, at the Ridgway House. R. Jones Monaghan was found in his room with the end of a rubber hose in his mouth and the room's gas “flowing full head.” No other details were given other than that his “occasional attacks of insanity have of late years made him the object of much publicity.” The attorney's eccentric behavior had been reported over the years as widely as in the

New York Times

.

The Ridgway was demolished in the 1930s, soon after the discontinuation of most ferry service between Philadelphia and Camden. A highway now passes where Mr. Monaghan took his life. The true ignominy of this situation, though, is that Market Streetâthe “most historic highway in America”âno longer reaches Delaware Avenue or the Delaware River as it did for some 290 years.

Modern hotels on Delaware Avenueâthe Hyatt Regency at Penn's Landing and the Comfort Inn Downtownâare two blocks away in either direction from the old Ridgway House site. Interestingly, all three of these imposing edifices were built on made-earth.

The 350-room Hyatt opened in 2000, although residents of Society Hill Towers tried to stop its construction because the twenty-two-story tower would block their view of the Delaware. (Another instance of conflict about who gets to use or enjoy the river!) The ten-story Comfort Inn hotel was built in 1987 on the site of a row of decrepit commercial structures that had narrowly missed being demolished for I-95 a few years before.

S

ECOND AND

H

IGH

S

TREETS

The intersection of Second and High Streets was the next town center of Philadelphia. A Quaker meetinghouse surrounded by a brick wall stood at the southwest corner. This was the Great Meeting House, built in 1695 and enlarged in 1755. Upon arriving in Philadelphia on a Sunday morning in 1723, Benjamin Franklin made his way to this place of worship to take in a fiery sermon (as per his experience in Boston). Not hearing anything at the silent Quaker meeting, he promptly fell asleep. A restaurant-nightclub and a food store occupy that spot today.

The Continental restaurant-martini bar is on the southeast corner. This hip place was a trailblazer in Old City's renaissance when Stephen Starr opened it in 1995. Its early success catalyzed the area, and other bars and restaurants soon followed. Today, Starr Restaurants is among the fastest growing multi-concept restaurant companies in the country.

The Old Court House (aka Town Hall) stood in the precise middle of High Street above Second. Built about 1707, the building served as Philadelphia's first city hall, prison, auction house and legislative hall. It was torn down in 1837, by which time the city's municipal work had been conducted at the Pennsylvania State House for decades.

It was at Second and High Streets that Stephen Girard was struck and knocked down by a horse-drawn wagon on December 21, 1830. The wheel grazed his head, causing a gash on his face and practically cutting off his right ear. Girard was then eighty years old, and his bleeding was severe. But he refused help. Retaining his composure, he got up on his own and made his way unaided to his home on Water Street. “I am an old sailorâ¦I can endure suffering,” he said as doctors cleaned his wounds. Girard died a little over a year after the accident.

C

HRIST

C

HURCH

S

TEEPLE

Anglicans of the Church of England in 1695 founded Christ Church just north of this still-busy intersection. They set up a small wooden place of worship on Second Street. They later decided to replace this with the most sumptuous church in the colonies. Constructed between 1727 and 1744, Christ Church is considered among the nation's most beautiful eighteenth-century structures, a superb example of Georgian architecture and a monument to colonial craftsmanship.