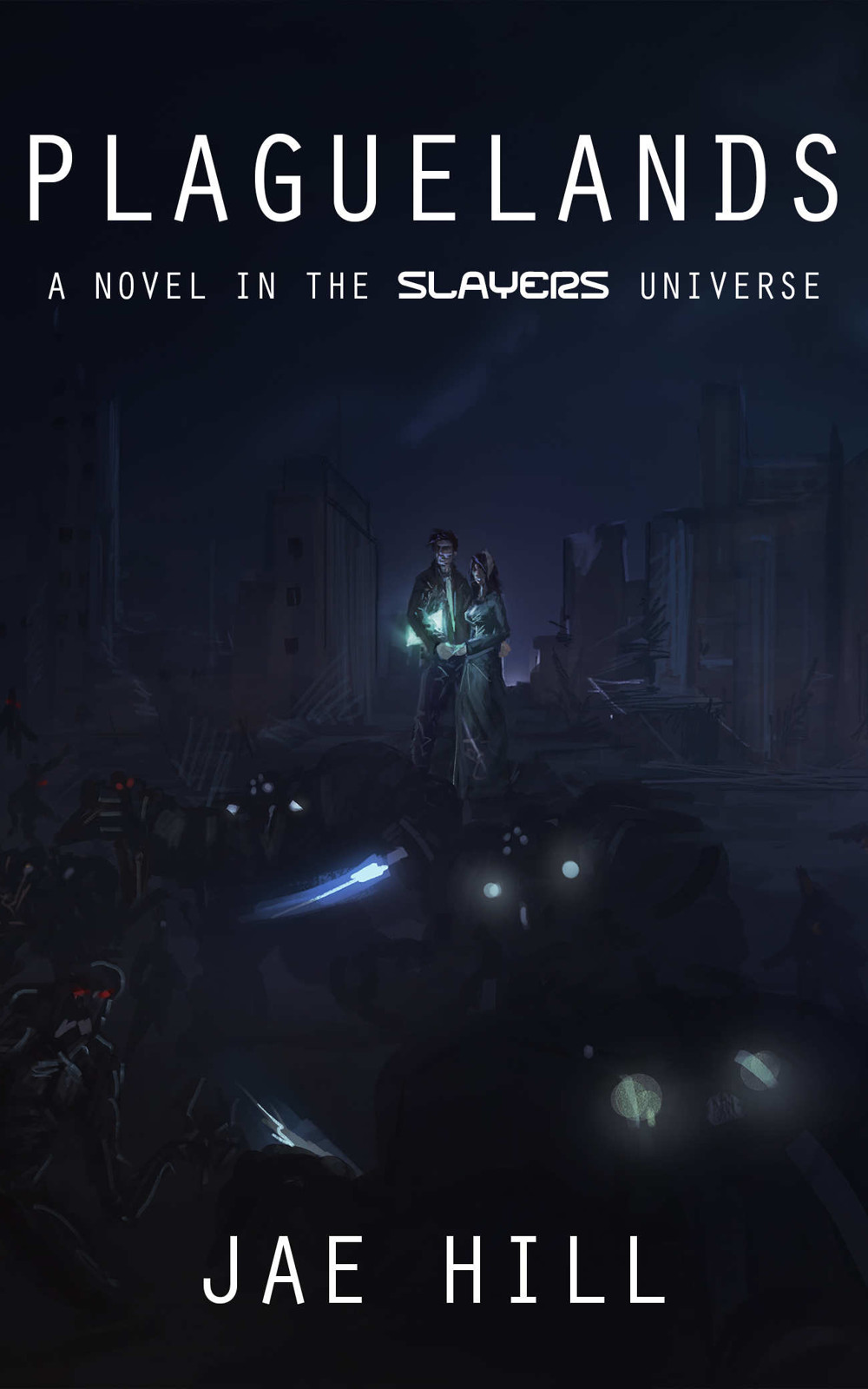

Plaguelands (Slayers Book 1)

Read Plaguelands (Slayers Book 1) Online

Authors: Jae Hill

Plaguelands

a novel of robots versus zombies

and part of the

Slayers

universe

by Jae Hill

Copyright © 2015 Jae Hill

and Alternis Games

All Rights Reserved

For Cristina

It had been several months since my two best friends had gone to the capital to undergo “the transformation”—a medical procedure where they would shed their human bodies for new eternal, robotic, “enhanced” forms. Semper Graham, the clumsily awkward engineering student, had been as close to a brother as I’d ever know, but I hadn’t heard from him in months. Adara Goodman—the annoying, bossy brat next door who’d grown into a raven-haired beauty—had departed shortly after Semper.

I was left in utter depression at the reality of losing my two best friends. I dove deeply into my university studies, hoping to get admitted early to the prestigious Astrophysical Institute on the planet Theron once I underwent the same transformation. My only solace was that I, too, would be leaving in just a few more months.

Everything changed right after my eighteenth birthday. I was now eligible for the procedure and just had to complete the final medical pre-clearances. A month before the operation, on a very dark and rainy evening, I came home from the medical center to find Semper sitting there in my bed, soaking wet, making some kind of droning noise. I turned on the light and was scared.

It looked like Semper. The shape of his eyes, the color of his skin, the wave of his hair…it was all there. I couldn’t immediately tell what was missing as I examined his body until I realized that he wasn’t breathing. He wasn’t shivering after being in the cold. No goosebumps on his skin. No wrinkled fingers. He looked empty. Fake.

The droning noise finally made sense. He was trying to cry but he had no tear ducts to leak salty droplets, no lungs to gasp, no throat to get choked up. He was trying to cry and that pitiful droning noise was all that his vocal speaker could translate the electric impulse as. His transformation was complete and he was not happy with the outcome.

He threw his arms around me in a big hug and then proceeded to tell me all about the procedure. How it wasn’t as peaceful or non-invasive as the adults led us to believe all our lives. It starts out seemingly innocent and safe. They tie you down and tell you that you’re going to experience all sorts of stimuli as they map your brain and that it may be unpleasant but they have to map

all

of your senses and movements while you’re awake. They tickle you. They play all sorts of music at all volumes—pleasant and deafening. They wet you down. They dry you off. Then they burn you. They cut you. They crush you with heavy weights. They freeze you. They break bones. They put holes in you. They torture you for an eternity that might be a few hours or a few days. You don’t know because they deprive you of your sleep. You feel hungry. You feel sad. And then you feel nothing.

The surgeons put your brain into a coma and begin the extraction process from your corporeal body to move your central nervous system into the enhanced body. The top and rear of your skull are removed. A serum causes the myelin sheaths of your nerve bundles to replicate and then shed, allowing the entire central nervous system to be extracted whole from your body. It’s slid right out through the top of your head. Like gutting a fish. The spinal cord is then slowly inserted into a similar hole in the head of the enhanced body and fitted into the new alloy backbone. The technicians begin guiding the major nerves into the right places. A few more fluids are introduced, causing the nerve fibers to grow rapidly and make contact with the servo motors and sensors waiting inside the enhanced body.

You wake up without your skin while a host of computer-driven arms hover above you, still connecting nerve fibers. The robotic arms are using your brain map to connect the proper nerves to the appropriate sensors and servos. The surgeons need to make sure that everything has connected correctly before they close you up. So again they run a bunch of other tests. They poke you. They apply a hot needle. You feel pressure, and you feel pain. You react normally, withdrawing your hands and feet, but the fear is gone. The pain exists for only an instant and doesn’t linger. When the tests verify that all of your millions of nerves are connected well-enough, they wrap you in your new skin. You fall asleep again…exhausted and terrified.

You wake up again in a big fluffy bed in a pure white room with soft filtered light pouring around you. You’re still restrained, but your adult family members are there to comfort you. They smile politely, but you notice the subtle differences now. That mom’s smile doesn’t quite crease the same as yours used to. That dad’s hands aren’t calloused like yours used to be. They are as devoid of their human body as you are now.

We were all told in the academy that you need to spend twelve months in the hospital to regain the use of all your functions again, but apparently that’s a lie. Semper said he went in for the procedure on Friday, the 28

th

day of Quartem, and he woke up in that white room on the 15

th

of Quintem. Seventeen days and he could stand right out of the bed and hug his family.

The problem is actually that you’re too strong. Without properly training your brain to use your enhanced body, you’ll break off door-knobs when you twist them or punch through walls when trying to place a push pin. The next three weeks after you wake up is simply learning to tone it all down. Learning to ignore the hypersensitivity of your audio receptors. Learning to control the pressure of your hand so you can use a pencil or a paintbrush without splintering it. Learning to control your panic when you realize that you’re not breathing. You have to learn to become human again.

No…actually you had to learn to pretend to be human.

By the end of the sixth week, you’re fine. You can walk around. You can do everything you could before, as well as you could before. But of course you no longer need to eat or drink or use the restroom. You sleep less and less until you’re at four hours of sleep per night and then you go into a self-programmed shut down, like a sleep-mode on a computer. Your pumps keep circulating and cleaning your fluids. Nanobots patrol your synthetic blood looking for pathogens. Artificial organs slowly synthesize chemical packs into useful nutrients, sleep chemicals, hormones needed for brain functions, and other enzymes. You need to replace the packs every three months, but they’ll last up to six in an emergency.

The worst part, according to Semper, is that you can’t eat, even if you want to. As kids with human stomachs and hormones, we’re hungry from birth and trained from birth to want to eat at the sight and smell of food. He said that he didn’t get hungry but longed for the food just the same. There’s no reason for people to eat after they complete their transformation. It is inefficient, illogical, and wasteful to create a mechanical body that needs food and processes it so poorly. The efficiency provided by our enhanced forms is why our people could take to the stars so readily. It’s easy to fly through space and visit new worlds where breathing, eating, and drinking are unnecessary.

Semper continued speaking, in hushed tones, for hours about the rest of his seven-month stay at the hospital. They keep telling you, he said, that you only need to stay a little bit longer until you move to the next tier, where you can interact with other post-op patients. They say this for weeks and then some unnamed doctor makes a determination that you’re safe to release to the public. But they test you out first. They put patients in small groups for a few weeks until they’re sure you’re okay with your body. But there’s still no release. You can read or watch videos. You can play board games or paint. But there’s no calling home and there’s no going outside. The sea-foam green walls are your only friend.

Every once in a while, someone disappears. There’s no warning. There’s no signs or symptoms or reasons. They disappear and you never see them again. Asking about it nets you a standard “confidential medical information” answer. Semper thinks that they can’t handle the transition and are shut down. Dismantled. Recycled. But there’s no proof.

I finally realized our parents never talked about their classmates. They talked about their childhoods. Life with their parents. Memories. A few scattered memories of distant friends. But never their academy cohort. The surgeons at the bionics facility once told us that one in ten thousand doesn’t survive the surgery. How high is that number really? And more importantly…how many just can’t handle the transition?

After six months in the medical center, Semper was free to move around the hospital as he wished, but couldn’t go outside. He once asked for a breath of fresh air, but was informed that such a request was unnecessary as he was no longer able to breathe, and that getting used to being sequestered in the facility was important so he could be accustomed to close quarters before decades of space flight. He only started to feel more and more claustrophobic.

Semper said he never felt fear. He logically knew something was wrong with himself. His mind longed for the food and fresh air, but his body didn’t need those things. No hormones surged. Even if one of the glands of his brain activated with fear or hunger, no other part of his body was programmed to receive that chemical response. His desires were illogical yet inescapable.

But the building was not.

Eight months into the process, Semper couldn’t handle it any longer and began fomenting a plan to escape. He had never been outside the maze of rooms. Technicians sat at desks, watching readouts from our bodies to make sure they stayed in operating condition. Doctors examined patients. Janitorial robots cleaned the floors and walls, which in the absence of germs and body fluids, was just to clear dust. A few patients gathered in the large living area to watch a television documentary on some newly discovered solar system. The outside wall was floor-to-ceiling windows of illuminated milky glass. He figured that once he was outside, he would just run home. So he launched himself through the windows…

…and found himself in another hallway, much to the confusion and amazement of the onlookers on both sides of the shattered wall. The windows led nowhere, but Semper ran just the same. An alarm sounded. Doctors with high-voltage tasers chased him down the hall. He dodged carts and threw whatever box or cart was in his way. Semper had no heart beating or adrenaline pumping, he just had the one last part of his humanity to spare: pride. He knocked over a taser-wielding doc and grabbed the electric gun, firing bursts of lightning back at his pursuers. Then, he bolted through the last set of double doors at the end of the hall and into the fresh night sky.

Semper could smell the air in a way that seemed new and unfamiliar. His new nose contained a sensor array that was a thousand times more sensitive than a dog’s nose. He almost took pause to explore the new sensation of the air wafting across his face, but instead he just ran and ran until he finally lost his pursuers.

Then, Semper snuck along through backyards and alleys until he found a freight truck heading north toward Valhalla. He ran as fast as he could, leapt atop the truck, and flattened his body against the wind for the hundred-kilometer journey. When he arrived in town, he crept to his house, where his parents were already talking to the police. He hoped he would be safe at my house, so here he was.

I was horrified. I couldn’t believe that everything my parents and teachers had told me growing up was a lie. The surgery wasn’t safe. It wasn’t easy. The transition was painful. It was life-ending. My bones and hair and teeth would all be thrown away like they were a waste. What else had the adults hidden from me? My head spun. My anger raged. I sobbed. And as we hugged each other on my bed, Semper would occasionally make a droning sound from his mouth.

I asked him if he’d seen Adara while he was in the hospital. He only nodded and then replied that she was dead.

“How can you be sure?” I asked.

“I saw her robotic body being hauled away. Lifeless.”

From the street below, I heard the quiet whirring of a car pulling up in the driveway. I peered out the window and saw two black-clad officers stepping out of the black police car. We didn’t have any police in Valhalla. In fact, I’d only ever seen police a few times in the capital. Their full-face helmets glinted in the low light, their knee-high leather boots crunched across the lawn.

We didn’t have any crime to speak of throughout most of our society. Greed. Fear. Anger. These are all emotions that have a nucleus in your brain, where chemicals are released to your other glands and organs to adjust your body chemistry. In our society, only the children experience these emotions on a chemical level, so only the children are prone to outbursts or minor offenses.

The adults, in their mechanically pure forms, don’t have the ability for chemical emotions. They don’t have the need for them, either. I remember reading that, during the first generation of enhanced bodies, the first humans to undergo the transformation were dismayed at the lack of humanity in their bodies. They could be disappointed, but never got sad or depressed. They could be upset, but never angry or abusive. They longed for the emotions to return. Scientists attempted to build some robotic forms with the ability to cry and eat and shiver, even though those actions are unnecessary and inefficient, but they would leave a measure of weakness and vulnerability to keep you feeling human. The attempts were only mildly successful and the few transplants that underwent the procedures with the “chemical bodies” reported that the emotions were too intense and not accurate responses. The project was aborted. Society as a whole decided that emotions were a gift for the youth, and a more logical and rational adulthood was the sacrifice needed to reach out to the universe beyond. So without greed and fear and anger, there is not a lot of murder or theft or violence: those actions are the hallmarks of the young or disturbed.