Poison (35 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“Strychnine?” Rieders said. “The first strychnine poisoning case I had was when I was a lowly apprentice in New York in 1949. A pharmacist who had murdered his wife. It’s not uncommon. You don’t see it every day, but at the medical examiner’s office in Philadelphia—I was there for what, 14 years—we’d get a case every year and a half or so.”

“All we have are the block tissues left from the victim,” Hrab said. “Could you look at those?”

“They are in paraffin wax blocks?”

“Yes.”

“I’ve studied paraffin block tissue, although none involving alkaloids like strychnine. Mostly for metals and some other drugs,” Rieders continued. “It would be a bit drawn out, and won’t be exactly cheap. But it would be worth trying.”

There was the issue of cost, which would be in the $30,000 range. But Steve Hrab could barely contain his excitement. In due course, Korol, Leitch, Bentham, and Joel Mayer from the CFS flew down to Pennsylvania to see Rieders. They were satisfied with what they saw. Rieders was hired to test 75 tissue samples from Parvesh Dhillon, one final chance to reveal her secret.

The preliminary hearing lasted 11 months and the Crown called 116 witnesses, among them CBI Inspector Subhash Kundu. Despite Dhillon’s attempts to intimidate witnesses, he suffered a major setback when Rai Singh Toor, Kushpreet’s father, took the stand. Dhillon expected Rai would help his defense, since the old man had signed the affidavit back home stating he did not suspect Dhillon was involved in his daughter’s death. But on the stand under Bentham’s questions, he now admitted that he had been intimidated into signing the affidavit.

The hearing ended 341 days after it began, on April 11, 1999. Provincial court Judge Morris Perozak ruled that there was sufficient evidence for Sukhwinder Dhillon to stand trial for murder in the deaths of Ranjit Khela and Parvesh Dhillon. As for Dhillon’s lawyer, Dean Paquette, it is normal for the defense lawyer at a preliminary hearing to also represent his client at the trial. But Paquette told Dhillon he would not represent him further. Dhillon needed a new defender.

Warren Korol’s white Lumina glided along Hamilton’s dark wet streets. An unusually intense winter sun burned off the morning frost. The whole week had been freakishly warm. It was Friday, December 3, 1999. He thought of the case all the time, it had become a part of him. Dhillon’s prelim hearing had ended eight months earlier. His trial for murder wouldn’t begin for another nine months. The court system moved like a glacier. Such a long process. Korol had been 35 years old when the Dhillon file first landed on his desk. Hard to believe it, but 40 would be in view by the time the trial opened in the spring. Korol smirked. He remembered the day, at age 18, after he had passed the Hamilton police entry tests that could put him in the cadet program, that he mounted the stairs at Central Station for the interview.

“So how’s Sally?”

The question was a reference to Korol’s aunt, Mike Pauloski’s widow. Korol heard back the next day from the police brass. He was hired. In other professions, start dates do not linger in memory. But

cops are different. The day you put on the badge is like a birthday. Korol never forgot his first day: July 30, 1979. He loved the work. He enjoyed reminiscing about legendary officers from the past, men like John Petz, Kerry Eaton—and Kenny Knowles, the cop who once exposed corruption among vice officers who were keeping confiscated liquor. One judge called Knowles “the prince of the city.” Knowles was a complicated man, however. He battled bouts of anxiety and depression and died very young, at age 44.

cops are different. The day you put on the badge is like a birthday. Korol never forgot his first day: July 30, 1979. He loved the work. He enjoyed reminiscing about legendary officers from the past, men like John Petz, Kerry Eaton—and Kenny Knowles, the cop who once exposed corruption among vice officers who were keeping confiscated liquor. One judge called Knowles “the prince of the city.” Knowles was a complicated man, however. He battled bouts of anxiety and depression and died very young, at age 44.

Like the Indians in Hamilton with whom he had spent so much time during this case, Korol’s roots did not run very deep in Canadian soil. His grandparents had emigrated from Ukraine to a wheat farm in Saskatchewan. They lived hard lives and died young, his grandmother during childbirth and his grandfather after a horse pinned him against a barn wall, crushing him to death. His father, Maurice, was one of 10 kids. As a kid, Korol visited relatives out west. They all pitched in at harvest time, dad showing the kids how to operate the combine and milk the cows. Great memories. But his father had died young, in 1984, at just 60. Heart attack. Warren’s mother, Lois, who had worked as a Bell telephone operator and was now retired, moved on, had to learn how to pay bills, drive the car. Rebuilt her life. Warren was proud of her.

His Lumina turned a corner. Korol’s pager beeped. The number was familiar. It was Brent Bentham. Korol punched in the number on his cell.

“Hey Brent, what’s up?”

Bentham, typically, hedged his remarks. All of the tests weren’t finished yet, he said. But there was some news. Dr. Fredric Rieders had completed his testing. Korol’s heart pounded.

And?

And?

“He found strychnine in Parvesh Dhillon’s tissue.”

Korol felt electricity coursing through him. Rieders’s testing had found strychnine concentrations of 200 picograms in the tissue samples. On one level, the amount was so small it was mind-boggling. But Rieders pointed out that the presence of strychnine is confirmed when a one-gram tissue sample contains only 30 picograms of the poison. By that measure, Parvesh’s tissue was soaked in strychnine. Later, the Crown arranged for a control test

to be done at a lab in Montreal that boasted equipment similar to Rieders’s. It, too, detected strychnine. Korol was pumped. This was the break. This was it! Parvesh had spoken from the grave.

to be done at a lab in Montreal that boasted equipment similar to Rieders’s. It, too, detected strychnine. Korol was pumped. This was the break. This was it! Parvesh had spoken from the grave.

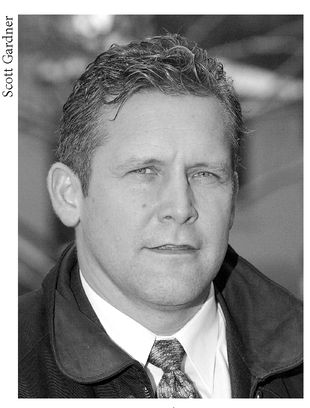

Detective Warren Korol

Sukhwinder Dhillon’s home in Barton Street jail had faded yellow-beige concrete walls, a tone so neutral, so devoid of emotion that it would not even qualify as a color. The cell contained two hard steel bunks with thin striped mattresses. If there was a third man in the cell, he slept on a mattress on the floor. There was a small white toilet, no lid, a miniature sink made of porcelain. Officials planned to substitute sinks made of stainless steel to prevent inmates from breaking off chunks that could be used as weapons.

In the corner of the room were books and magazines belonging to Dhillon’s cellmate. Six of each, the maximum allowed. No posters were permitted on the walls. No graffiti, either. But following the rules isn’t a strong suit for recidivists. So there were the crude pencil drawings of naked women. Opinion: “I hate this f—ing hell hole.” Advice: “Don’t commit crime.” And: “I will boldly go where no man has gone before … so bend over bitch.”

Beyond the confines of the cell was a common room with a TV where 30 men crowded for their allotted leisure time. Five metal tables were welded to the floor. No eating there, though. All meals were brought to the cells so inmates could not intimidate each other into handing over food. Inmates decided among themselves what to watch on TV each day. The rules say no “muscling” is allowed, that is, no intimidation to get your way. The prisoners

were in their cells and lights out at 8 p.m. every evening. Each inmate is entitled to two visits a week, two people maximum per visit. After an extended stay or return engagements, life in jail becomes a “learned environment” for inmates, as prison officials put it. They learn to coexist, keep quiet at bedtime. They use the regimented meal routine to control their bodily functions, to go to the toilet only when a cellmate is not in the room.

were in their cells and lights out at 8 p.m. every evening. Each inmate is entitled to two visits a week, two people maximum per visit. After an extended stay or return engagements, life in jail becomes a “learned environment” for inmates, as prison officials put it. They learn to coexist, keep quiet at bedtime. They use the regimented meal routine to control their bodily functions, to go to the toilet only when a cellmate is not in the room.

The first time in jail for anyone is like a punch in the face. Life is suddenly flipped into another dimension. The new prisoner is trapped in small rooms of steel and concrete with strangers who may have maimed or raped or killed. He is surrounded by men with hard, pale faces, many possessing a vacant stare. There was at least one jailhouse incident involving Dhillon. Just before curfew one night in April 1998 he got into a fight with another inmate. Dhillon claimed he was stabbed. He was treated at Hamilton General Hospital and returned to his cell. His injuries were superficial. Police and jail officials were not able to establish what had happened.

Family members and a few old friends came to see Dhillon during visiting hours. They waited in line, single file, for their 15-minute visit. The waiting line outside the jail is a theater of the tragic. It is frequently made up entirely of females, often rough women with long hair framing leathery faces decorated with dark eyeliner and harsh blush. They wait to see their men, to sit on a round iron stool on the other side of a completely sealed window, able to talk only by telephone. The women wait their turn beneath a No Smoking sign, lit cigarets in hand.

“I found God a while back,” one of them says. She hopes her guy in the House will find the Lord, too. “Patience and faith. Patience and faith. It’s all about patience and faith,” she adds, reciting her sermon in the smoky haze to the others.

“You can’t expect God to deliver this week or the next. You have to wait. That’s where strength comes from. You know? I pray for the little things. Yeah. They say you can’t do that, no, but you can. I’ll pray for a roll of toilet paper if I have to. I prayed my little girl would be potty-trained. Two days later, off came the diaper.”

“

Next

.”

Next

.”

A voice drones over the outside intercom. The line shuffles forward.

Last time she visited Jimmy in jail she wore the miniskirt, platform shoes. Oh yeah. He was jealous. Big time! “You wonder if the guards read the letters, eh? I mean, I hope not. They’ll think, f--k, that woman is crazy, one day she’s writing all this religious shit, deeply religious, born again. The last letter, it was a steamy one, I mean hot.”

“

Next

.”

Next

.”

She walks inside to the visitors’ room and waits on a metal stool for Jim, who is then led into the room, on the other side of the glass. They smile and flirt over the phone. He talks bitterly about the guards. They are assholes, he says. He is not being treated right.

“I know, I know, sweetie,” she says. “I know—look, you need to feel compassion for these people. Feel compassion for those who hate you. It’s the way of Jesus.”

A journalist with

The Hamilton Spectator

waited behind the glass, too. He visited Dhillon, unannounced. He was working on a series about the case. The jail-side door opened, and Dhillon appeared. He wore an orange jumpsuit and rubber-soled canvas loafers without laces. Without the square-shouldered suit he wore in court he looked rounder, less menacing, smaller. Dhillon spotted the writer and, not recognizing him, turned to the guard, a surprised look on his face. The guard shrugged. Dhillon took a step toward the window, then away from it, then toward it again, back and forth, looking like a frightened, confused, caged animal.

The Hamilton Spectator

waited behind the glass, too. He visited Dhillon, unannounced. He was working on a series about the case. The jail-side door opened, and Dhillon appeared. He wore an orange jumpsuit and rubber-soled canvas loafers without laces. Without the square-shouldered suit he wore in court he looked rounder, less menacing, smaller. Dhillon spotted the writer and, not recognizing him, turned to the guard, a surprised look on his face. The guard shrugged. Dhillon took a step toward the window, then away from it, then toward it again, back and forth, looking like a frightened, confused, caged animal.

Other books

10 Great Rebus Novels (John Rebus) by Rankin, Ian

Outage (Powerless Nation #1) by Ellisa Barr

Operation Underworld by Paddy Kelly

Beekeeping for Beginners by Laurie R. King

Seaspun Magic by Christine Hella Cott

My Father's Notebook by Kader Abdolah

Corporate Seduction by A.C. Arthur

Rude Astronauts by Allen Steele