Poison (33 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

While police helped Lakhwinder retrieve her son, Korol and Dhinsa attended the autopsy room at the Ontario coroner’s office, along with Hamilton Police forensic detective Larry Penfold. Rarely had an autopsy drawn such an audience. Dr. Charles Smith and an assistant named Jeff Arnold were about to perform autopsies on Dhillon’s two infant sons. Also in the room were Jim Cairns, Ontario chief coroner James Young, biologist John Newman, and toxicologist John Kertesz from the CFS. Korol approached the two aluminum boxes on the gurney. There was a sharp cracking noise as he cut the first padlock.

“We can check everything here, every item, the clothes, tissue, dirt, for strychnine,” Kertesz said.

Newman said a major bone from each of the skeletons would be required to confirm through DNA that Sarabjit was their mother. Penfold catalogued every tissue sample held up and described by Smith, and took photos of them. The first autopsy finished, Korol cut the second lock and Smith began work on the body inside. There wasn’t much to examine.

CHAPTER 18

CHEMICAL COCKTAIL

Dhillon continued selling used cars at Aman Auto, with little regard for his situation. He hired a young woman to do clerical work at his dealership. Her name was Terri, 19 years old, blue eyes, blond hair. One day, he took Terri out for lunch to an Indian restaurant.

“My wife died two years ago,” he told her quietly. “She had been sick for a long time.… You’re a pretty girl,” he said. “Very pretty.” Terri told him she had a boyfriend. And then one day he handed her a videotape and said she and her boyfriend would enjoy it. Later she was with friends and popped the tape into the machine. It was pornography.

“Gee, Terri, nice boss,” one of her friends cracked.

“Yeah, I know how to pick ’em.”

Another time, Dhillon asked to take her to a “business meeting.” She must dress conservatively, cover her head, show no skin but her face. Terri declined. When she didn’t respond to his advances, Dhillon asked her to fix him up with her friends. Dhillon wasn’t paying her on time, and then not at all. She told Dhillon she was going to call the cops. Dhillon paid her right away. Then she quit in September. A month later, she watched the news on TV about an arrest made by police. Terri was alone at the time, staring as the accused man’s confused face flashed on the screen.

“Hey,” Terri said aloud, to no one. “That’s my old boss!”

It was Wednesday, October 22, 1997, when Korol and Dhinsa met in Brent Bentham’s office. Once more they reviewed the case. Dhillon had motive and opportunity in the murders of Parvesh and Ranjit. Disposition? There was evidence that Dhillon was a liar, a fraud, a bigamist, a wife beater. They had forensic evidence that said Ranjit was poisoned, although they did not have that smoking gun for Parvesh’s death. As for the evidence from India, they were still waiting on forensics, but witness statements strongly suggested Dhillon had poisoned his sons and his third wife, Kushpreet. The deaths in India could be used as “similar-fact” evidence that would create a mountain of probability pointing to Dhillon’s guilt. Bentham did not leap into cases. He had to have a

strong shot at conviction or he would turn down a case and have no second thoughts about it.

strong shot at conviction or he would turn down a case and have no second thoughts about it.

“You have more than reasonable grounds to arrest for these murders,” Bentham said in his deep baritone. “And upon reviewing the evidence, as the Crown attorney, I would add that there is the likelihood of conviction.”

Police had Dhillon under surveillance that morning. He was at his car dealership. At 9:30 a.m., the morning bright, crisp, and cool, Korol, Dhinsa, and Steve Hrab left Central Station. They made the 10-minute drive to Aman Auto. It had been almost two years and nine months since Parvesh collapsed. The unmarked white Crown Victoria pulled into the tiny parking lot and the detectives got out, knocked on the door. Dhillon walked out wearing a fall jacket over his long-sleeved shirt and dress pants. He was used to Korol and Dhinsa visiting him. But not at work. And not with Hrab, the one who had grilled him 10 months earlier. Dhinsa pulled the caution card out of his wallet and read it in Punjabi. “I am arresting you for the murder of Parvesh Dhillon and Ranjit Khela.”

As Dhinsa spoke, Korol cuffed Dhillon. Click. Click. It felt good. Dhillon, Korol reflected, you are easy to hate. But he knew the fight was just beginning. Dhillon looked calm, even indifferent. He was confident it was a mere formality and he wouldn’t be under arrest for long.

“You have the right to telephone, in private, any lawyer you wish. Do you understand?”

Dhillon nodded.

“I want to call a lawyer.”

“Do you wish to say anything in answer to this charge?” Dhinsa asked. You are not obliged to say anything unless you wish to do so, but whatever you say may be given in evidence.”

“What can I say—I didn’t do anything,” Dhillon said. “Don’t worry about it. I know you’re just doing your job.”

At Central Station, just after 10 a.m., Korol searched him. Then Dhillon called his lawyer, Richard Startek. He asked if he could also call a friend.

“No,” Dhinsa said.

The detectives escorted Dhillon to cell No. 4 on the second floor. Dhinsa worked the phones. He called the Khelas and spoke to Paviter Khela, Ranjit’s uncle. “You must have something substantial on him to charge him,” the uncle said.

At 11:30, Dhinsa opened the window looking in on the cell. Dhillon sat on the bench appearing nonchalant, his feet resting on a chair.

“Suspect looks well,” Dhinsa wrote in his book. “Feet up on a chair.”

At 1 p.m. Dhillon was permitted to phone his niece, Sarvjit. He asked about his daughters, Aman and Harpreet. He told Sarvjit to contact another friend and ask him to look after Dhillon’s business at a car auction in Kitchener.

“Don’t worry,” he told Sarvjit. “I’ll be back in two or three days. Everything will be fine. I didn’t do anything. The police can do whatever they want, but I didn’t do anything. Tell Harpreet I’ll call her tonight.”

He ate a sandwich of processed cheese on dry bread, drank a coffee. At 3 p.m., the detectives questioned him, first Dhinsa, then Korol, while others watched in the video room next door. A half-hour later, Korol booked Dhillon. At 5:43 p.m., Dhinsa phoned India to tell Sarabjit the news. It was the middle of the night there. He spoke to Sarabjit, and then her father, Gurjant. They were both relieved to hear the news.

The next morning Dhillon was loaded into a paddy wagon with several other men and taken to court downtown for a bail hearing. He was remanded in custody. His next stop was Barton Street jail. He was escorted through the back entrance, the sound of metal clanking against metal echoing off the concrete walls and along the corridors, and into his cell. His world, which had once stretched from Hamilton to the Punjab, was now just five paces long and three paces wide, with a toilet behind the door.

“Mein bekasoor haaan. Mein kujh vee galat naheen keeta.”

“I’m innocent,” Dhillon said. “I didn’t do anything wrong.”

He phoned friends and family from jail. He spoke frequently with his niece Sarvjit. “Whatever people are saying, they are all lies,” he told her. “I don’t know who is spreading them. People are spreading a lot of rumors and the rumors came to the police.”

His behavior in India? He had been under pressure—such pressure!—when he had gone to Punjab. All those parents calling for him to take their daughters. Please marry her! Please! He could have married any of them. It went on like this, Dhillon maintaining his innocence, trying to implicate others. It was not his fault, any of it. He told anyone who would listen that he had been framed by rivals jealous of his success as a businessman. And Kevin Dhinsa was out to get him.

“Dhinsa

, teri ma noo. Jidan mein bahar aa gia, udan mein os mader chod ... Dhinsa nu kutnaa hey, Usdeeaan lataan torneeaan ney

.”(One day, when he gets out of jail, I will beat on Dhinsa, that motherf—er, break both his legs.)

, teri ma noo. Jidan mein bahar aa gia, udan mein os mader chod ... Dhinsa nu kutnaa hey, Usdeeaan lataan torneeaan ney

.”(One day, when he gets out of jail, I will beat on Dhinsa, that motherf—er, break both his legs.)

One more thing, Dhillon assured Sarvjit:

“

Chintaa dee koee gal naheen. Ik din taan mein bahar aa hee jaana hey, lokaan nu pher sach pataa lag hee jaaegaa.

” (“Don’t worry. I’ll be out one day. And then people will know the truth.”)

Chintaa dee koee gal naheen. Ik din taan mein bahar aa hee jaana hey, lokaan nu pher sach pataa lag hee jaaegaa.

” (“Don’t worry. I’ll be out one day. And then people will know the truth.”)

The spring of 1998 was the hottest in 50 years in Hamilton. The weather seemed to skip from the dead of winter to summer heat and rain in May, jerking white and purple lilacs prematurely to life. Then the rain stopped, leaving the blooms hung out to dry. The preliminary hearing into the murder charges against Sukhwinder Dhillon started on May 5, 1998, in an old courthouse at 140 Hunter St. E. downtown. A judge would decide whether the evidence warranted proceeding to a full trial. High-profile criminal lawyer Dean Paquette had replaced Richard Startek as Dhillon’s counsel.

Parvesh Dhillon’s cause of death was still conjecture, based purely on the symptoms she had exhibited. There was no question Ranjit Khela had been killed by strychnine. But who had given it to him? The evidence that Dhillon poisoned Ranjit was

both the Crown’s trump card and its Achilles heel. It relied on Lakhwinder. Paquette, a former Crown prosecutor himself, tore her credibility to pieces over the three days she was in the witness box. She was an easy target. Paquette pointed out to her that she had said nothing about Ranjit taking a pill when Korol and Dhinsa first interviewed her in September 1996. She also did not mention it in a second interview some time later. Only in her third interview with police did she offer her current version of the truth. What was the real truth? And what was her angle? She did not get along with Ranjit’s family, and there was talk she was about to divorce him. She had served Ranjit his last meal not long before his death.

both the Crown’s trump card and its Achilles heel. It relied on Lakhwinder. Paquette, a former Crown prosecutor himself, tore her credibility to pieces over the three days she was in the witness box. She was an easy target. Paquette pointed out to her that she had said nothing about Ranjit taking a pill when Korol and Dhinsa first interviewed her in September 1996. She also did not mention it in a second interview some time later. Only in her third interview with police did she offer her current version of the truth. What was the real truth? And what was her angle? She did not get along with Ranjit’s family, and there was talk she was about to divorce him. She had served Ranjit his last meal not long before his death.

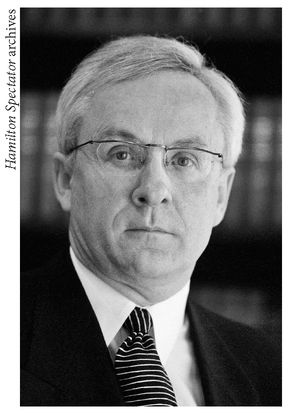

Defense lawyer Dean Paquette

Dhillon requested that he sit near the witness box, claiming that he could not hear what Lakhwinder was saying in Punjabi to the interpreter. He gleefully watched her struggle under cross-examination. Dhillon couldn’t stand her, muttered epithets when she spoke.

The Crown’s case had suffered a blow even before the hearing began. On April 22, Korol got a call from Joel Mayer at CFS. The test results from the remains of Gurwinder and Gurmeet showed the babies had likely been poisoned, but not necessarily by strychnine. The toxicology tests had found a cocktail of drugs in the bits of sinew hanging off their bones. Without a blood sample, it was impossible to tell how much they had ingested. At least six substances were detected:

• Harmine, a hallucinogenic drug, the key ingredient in a potent South American drink called

ayahuasca

, which is used among those of the Sao Daime faith in the Brazilian Amazon. The drug has no therapeutic use.

ayahuasca

, which is used among those of the Sao Daime faith in the Brazilian Amazon. The drug has no therapeutic use.

• Dicyclomine, an antispasmodic drug, a fine, white, crystalline powder with a bitter taste. Odourless and soluble in water.

• Diphenhydramine, an antihistamine, also used for gastrointestinal problems and for relieving spasms and cramps in the digestive system.

• Promethazine, an antinausea drug.

• Cotrimoxazole, an antibacterial drug commonly used in recent years in Third World countries to prevent secondary HIV infection.

• Doxylamine, a sleeping aid.

Other books

Son of a Dark Wizard by Sean Patrick Hannifin

Primal Instincts by Susan Sizemore

The Girl With No Name by Diney Costeloe

Love & Hate (Book Two: Love) by JJ Dorn

Racing to You: Racing Love, Book 1 by Robin Lovett

A Pirate of her Own by Kinley MacGregor

Abby the Witch by Odette C. Bell

Cuffed & Collared by Samantha Cayto

Save Me From Myself by Stacey Mosteller

Hot for Him by Amy Armstrong