Pompeii (16 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

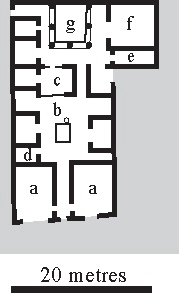

Figure 6

. The House of the Tragic Poet. Visitors entered this house between two shops (a), down a narrow passageway to the atrium (b), with its porter’s cubby-hole (d). Beyond the

tablinum

(c) with its mosaic of actors preparing (Plate 17), was the garden (g). Opening onto it was a

triclinium

(f ) and kitchen (e).

The original remains of this house are to be found in the north-west corner of Pompeii, between the Herculaneum Gate and the Forum – directly across the street from one of the main sets of public baths, and a near neighbour, just two small blocks away, of the vast House of the Faun. Named, when it was excavated, after one of its wall paintings – then believed to depict a tragic poet reciting his work to a group of listeners (now re-identified as the mythical scene in which Admetus and Alcestis listen to the reading of an oracle) – the house was built in its present form towards the end of the first century BCE. The surviving decoration, including a striking series of wall paintings which featured scenes from Greek myth and literature, is somewhat later, the result of a makeover in the decade or so before the eruption. A few years after they were discovered, most of the figured scenes were cut out and taken to the museum in Naples, creating unattractive scars on the walls of the house. What was left in place – the surrounding patterns and the general wall colouring – is now dreadfully faded, despite the fact that it was roofed over in the 1930s to protect it from the elements. The impact is obviously much less breathtaking than when it was first discovered. That said, we can still fairly confidently reconstruct its ancient appearance and organisation, as well as glimpse something of the tremendous impression it made on visitors in the nineteenth century.

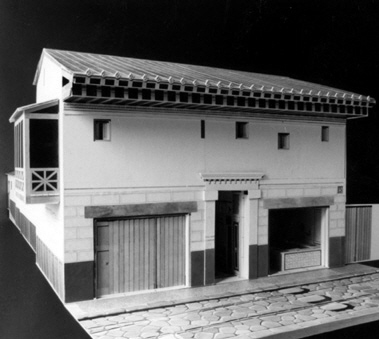

31. A reconstruction of the outside of the House of the Tragic Poet. With one of the shops shut, and only a few windows on the upper storey, the appearance is rather forbidding. The overhanging balcony at the side was a more common feature of Pompeian architecture than we would now imagine; made of wood, few have survived.

The façade of the house onto the main street (Ill. 31) is dominated by a pair of shops, in a good position to attract customers from the public baths opposite (in fact there is a strategically placed set of stepping stones across the road at this point). What they sold we do not know. In the one to the left some precious pieces of jewellery were discovered, gold and pearl ear-rings, bracelets, necklaces and finger-rings. But there was not enough to prove, as some archaeologists have suggested, that it was a high-class jewellery outlet (these things might, after all, have been the contents of a jewellery box that was never rescued). There were few windows, and those that there were, small and on the upper storey, well above eye-level. But between the shops was the grand entrance to the house, more than three metres high, fitted (as we can tell from the pivot holes on either side of the threshold) with double doors. Just to the left of this some signpainters had been busy, painting on the door pier a notice of support for Marcus Holconius, who was standing for the office of aedile, and for Caius Gavinius. Presumably this had been done with the owner’s encouragement or, at least, permission; if not, it was extremely cheeky use of someone’s doorpost.

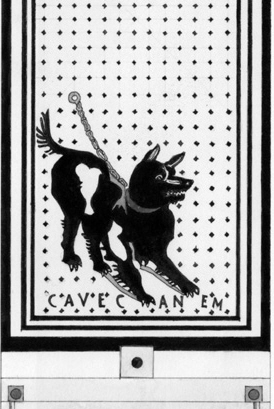

32. At the front entrance of the House of the Tragic Poet, marked here by the round fixings for the door, was this mosaic of a guard dog, and underneath the words

CAVE CANEM

. The round hole below in the centre is a drainage hole – water conscious as the Pompeians always were.

Here the doors themselves have not survived, but in other houses it has occasionally been possible to make a cast of them by the same technique as has been used for the bodies of the victims – filling with plaster the hole left by their decay. From these we get a stark, and more than slightly forbidding, impression of a great barrier of wood, with metal fittings and studded with bronze, dividing the house from the outside world. There can have been no practical necessity for portals of quite this size, strength and splendour. They were there to make a visual impact on visitors and passers-by: as much a symbolic boast, as a physical barrier.

Not that the doors were always closed, of course. At night, they surely did shut off the house and its activities from the world of the street. In the daytime, they may often have been open, allowing a view into the interior. If that was not the case, then the point of one of the House of the Tragic Poet’s most iconic images would have been lost. For directly on the other side of the threshold, and just past the small drainage hole for overflow water that must sometimes have flowed down the front hall from inside the house, is a memorable image in mosaic of a dog, teeth bared and ready to pounce were he not chained up (Ill. 32). In case you missed the point, he is accompanied by the words

CAVE CANEM

(‘beware of the dog’). This would only have been visible if the front doors were ajar.

There are other such warning signs in Pompeii, in paint as well as mosaic, not to mention the plaster cast of the real-life dog which died still tethered to his post. One is actually described by Petronius in his novel, the

Satyrica

, written during the reign of the emperor Nero. Much of the book has been lost or survives only in snatches, but the most famous and best-preserved section is set in a town somewhere near the Bay of Naples and features a dinner party given by an ex-slave called Trimalchio – a man of staggering riches, but of sometimes frankly grotesque taste. When the novel’s narrator and his friends arrive at Trimalchio’s front door, the first thing they see is a notice pinned right next to it: ‘No slave to leave the premises without permission from the master. Penalty 100 lashes’ (a nice touch from one who had once been a slave himself ). Then they come across the porter, flamboyantly dressed in green with a cherry-red belt, who is keeping watch over the doorway while shelling peas into a silver bowl; and, hanging over the threshold, a magpie in a golden cage sings a greeting to the visitors. But the real shock comes next: ‘I almost fell flat on my back and broke a leg,’ explains the narrator, ‘because on the left as we went in, not far from the porter’s cubby-hole, was a huge dog, tethered by a chain ... painted on the wall. And written above him in capital letters it said

CAVE CANEM

, BEWARE OF THE DOG.’ Just for a minute, he has taken the picture of the dog for the real thing – only the first of many occasions at Trimalchio’s dinner party when the guests will not quite know whether to believe their eyes.

It would be dangerous to take Petronius’ fantastic novel too literally as a guide to daily life in ancient Pompeii. But it does offer a hint here of how we might reconstruct the scene at the entrance of the House of the Tragic Poet. The door was very likely open for much of the daytime. But the security would not have been left to the mosaic guard dog, however fearsome or lifelike it might have been, or even to the actual dog signalled by the image (like the one which Trimalchio later brings into his dinner party, with predictably disruptive results). Almost certainly a porter, albeit more modestly dressed than Trimalchio’s, would have kept an eye on who was coming and going. In fact a small room just inside the house, under the stairs, with a rough floor, has been tentatively identified as the porter’s cubby-hole.

Visitors who stepped over the threshold found themselves in a corridor, once brightly painted, though precious little colour now survives. A narrow door from each of the shops opens onto this, suggesting that whoever owned the house was closely connected with these two commercial establishments; even if he did not service them himself, he was probably their proprietor and reaped the profits. Or that at least is the modern view. Earlier observers were more puzzled by this layout. In the absence of any obvious fixtures and fittings, despite the wide openings characteristic of shops, Gell wondered if they were not shops at all but quarters for the servants. Bulwer-Lytton trailed a different idea. They were, he suggested, ‘for the reception of visitors who neither by rank nor familiarity were entitled to admission’ into the inside of the house. Bright ideas, but certainly wrong.

At the end of the corridor you came into the house proper, arranged around two open courts (Plate 8). The first, the atrium, was again lavishly decorated – including six large wall paintings of scenes from Greek mythology. At its centre the roof was open to the skies, and underneath the opening a pool collected the rainwater, which drained into a deep well. On the well-head, you can still see the deep grooves made by the ropes which brought the buckets up, full of water from below. A number of mostly rather small rooms, some brightly painted, opened directly onto the atrium, while stairways ran up on either side to whatever lay on the upper floor. Beyond the atrium was a garden, lined on three sides by a shady colonnade (an arrangement known as a ‘peristyle’ – meaning ‘surrounded by columns’), with more rooms, including a kitchen and latrine, opening off it. One of these columns has the name ‘Aninius’ scratched on it twice: the owner of the house, some archaeologists have suggested; but equally well, a friend, relative, bored guest with time on his hands, or the name of someone’s heartthrob lovingly inscribed. The back wall of the peristyle supported a small shrine, and continued the garden theme, being covered with illusionistic paintings (now completely vanished) of trelliswork and foliage (Plate 9). In the very back corner, another door led out into the lane which ran up the side of the house.

We do not know how this particular garden was planted and stocked (though the shell of what was probably the household’s pet tortoise was found there). But new techniques developed long after 1824, such as the analysis of seeds and pollen, or the careful excavation, and plaster-casting, of the root cavities, have allowed archaeologists to reconstruct in vivid detail gardens in other houses. In one, the House of Julius Polybius (where the remains of the pregnant girl were found), the garden – about twice the size of this one – turned out to have been more of an orchard-cum-wilderness than the display of elegant, formal flowerbeds we often imagine. In a space of some 10 by 10 metres there were five large trees, including a fig (to judge from the large number of carbonised figs discovered), an olive and a variety of fruit trees, apple, cherry or pear. Some were so large that they needed stakes to hold up their branches. They were tall too: the imprint of a ladder, eight metres in length, which must have been used for picking the fruit, was detected by the excavators on the ground surface. But, even so, the owners of the house had packed more in. In the shade of the branches, other small trees, shrubs and bushes were growing, and there were eight more trees espaliered (or so the pattern of nail holes hint) to the west wall of the garden. Fragments of terracotta around the roots of these show that they had been started out in large pots, then replanted. Perhaps they were more exotic species needing more careful early tending, such as lemon. Overall it must have been a dark and shady area. It was certainly dark and shady enough to make a comfortable environment for the ferns whose spores were found in large quantities at the garden’s edge.