Pompeii (19 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The obvious answer, based on our own experience, that the upper floors were designed for sleeping is probably only partially right. The principal occupants of the house would have slept downstairs. We often find the traces of a fitted bed or couch still visible in those small rooms off the atrium or peristyle and others would have had similar, but movable furniture – though even these were not necessarily ‘bedrooms’ in our narrow sense of the word, but rooms where the couch could do duty as both sofa and bed, used by day and night. The upper floor was perhaps more likely to be used by the household slaves for sleeping, if they did not just lie down on the floor in the kitchen, at the master’s door or at the foot of his bed, or sometimes, of course,

in it

, given the sexual duties that ancient slaves might be expected to perform. Another view would see here more rooms for the ancient equivalent of lodgers, who would have accessed their quarters upstairs from inside the house itself, perhaps not using the grand front door from the main street, but one of the back doors that most houses had. In truth, we are probably dealing with a mixture of all three uses: attic storage, bedrooms, and rooms or apartments to let.

In one relatively small house (the House of the Prince of Naples, named after the local aristocrat who witnessed its excavation in the 1890s), there are no fewer than three staircases leading to rooms on the upper floor. One leads up from the street outside, to – presumably – a separate rented apartment. Another leads up from the atrium to what were at best a few dingy rooms. The most recent archaeologist to study this house thought these were most likely sleeping quarters for a handful of slaves. They could equally well have been attic storerooms. Another stairway went up from the kitchen, to rather brighter accommodation which overlooked the garden. Perhaps this was another rented apartment (but accessed from the kitchen?), or more quarters for domestic slaves, or maybe for the children of the house with their slave carers. This last option would be one solution to another little Pompeian problem: where did the children sleep? Apart from a single wooden cot found at Herculaneum (Ill. 33), we have no evidence at all of any special provision for sleeping infants. They must simply have bedded down with adults, either their parents or much more likely slaves.

The even bigger question that the upper storeys raise is how many people would have lived in one of these houses, and – leaving aside the apartments with their own independent street access – what kind of relationship would they have had to one another. Pompeian houses were not usually occupied by just one married couple, their children and a couple of faithful retainers. Anyone who once studied Latin using the

Cambridge Latin Course

and its (partly) imaginary Pompeian family should put the idea of Caecilius and Metella, their son Quintus, with slaves Clemens and Grumio, the cook, right out of their minds.

Well-off Romans lived in an extended family. This was not the loose mixture of cohabiting grandparents, aunts, uncles and a variety of cousins which we usually mean by that term (a mixture that is anyway more nostalgic fiction than historical reality). It was rather an extended

household

– or

houseful

as one scholar has more aptly put it – consisting of a more or less ‘nuclear family’ and a wide array of dependants and hangers-on. These included not just slaves (and there may have been very many of these in the richest households), but ex-slaves too.

In Rome, unlike the Greek world, domestic slaves were often granted their freedom after long years of service: an act of apparent generosity on the part of the master, which sprang from a mixture of humanitarian fellow-feeling and economic self-interest – for it got rid of the expense of feeding and supporting those no longer fit for much work, while also acting as an incentive to the others to remain obedient and hardworking. The fictional Trimalchio was very much an exception among this class. Most ex-slaves remained in various ways attached and obligated to their old master and his family, running their shops and other commercial enterprises, even still living on the premises – perhaps now with their own wives and children. In fact, the Latin word

familia

does not mean ‘family’ in our sense, but the wider household

including

the slaves and ex-slaves.

So adding together the nuclear family of the house owner, the slaves and ex-slaves, and the lodgers, how many people would have been resident in a house like the House of the Tragic Poet? The truth is we can only guess. One idea has been that the number of beds might help the calculation. But even when we find a clear trace of one, we cannot be certain that it was actually used for sleeping, or, if it was, how many people it would have contained. (Recognisably ‘double beds’ are not found at Pompeii or Herculaneum, though many do seem large enough to hold more than one occupant, adult or child.) And the number of people we pack in upstairs or imagine sleeping curled up on the floor is quite imponderable. One recent estimate for the House of the Tragic Poet gives a figure around forty. In my view, this is much too large. It involves housing no fewer than twenty-eight sleepers upstairs, and, if multiplied across the whole city, would give an implausible total of 34,000 inhabitants. Nonetheless, even if you halve it, it offers an image of a relatively crowded lifestyle, a very long way from Bulwer-Lytton’s idea of the sophisticated bachelor pad – and with considerable pressure on that single lavatory.

But reconstructing the houses of Pompeii demands more than filling in the gaps of what has been lost, satisfying as it is to restock those bare atria with their cupboards, looms, screens and curtains, not to mention the odd sleeping slave. There are also bigger issues of what these Pompeian houses were for. To reflect on these, we must look at how the one surviving Roman discussion of domestic architecture presents the purpose of the house and how that can help us understand what remains at Pompeii.

Show houses

An important guide to the social function of the Roman house is Vitruvius’ treatise

On Architecture

, probably written in the reign of the emperor Augustus. Vitruvius is largely concerned with methods of construction, public monuments and city planning, but in his sixth book he discusses the

domus

or ‘private house’. It is at once clear that, for him, it was not ‘private’ in the sense that we usually mean. For us, ‘home’ is firmly separated from the world of business or politics; it is where you go in order to escape the constraints and obligations of public life. In Vitruvius’ discussion, by contrast, the

domus

is treated as part of the public image of its owner, and it provides the backdrop against which he conducts at least some of his public life. Roman history provides telling examples of just that kind of identification between a public figure and his residence: when Cicero is forced into exile, his adversary pointedly demolishes his house (which Cicero rebuilds on his return); shortly before the assassination of Julius Caesar, his wife had a dream in which the gable of their house collapses.

Vitruvius recognises that different areas of the house have different functions. But the distinctions he suggests are unexpected. He does not, for example, suggest that the house be divided into men’s and women’s areas (as it regularly was in classical Athens). Nor does he suggest a division by age: there are no ‘nursery wings’ in Vitruvius’ ideal house plan. Instead he draws a distinction between those ‘common’ parts of the house which visitors may enter uninvited, and the ‘exclusive’ parts into which guests would only venture if they were invited. The ‘common’ parts include atria, vestibules and peristyles; the ‘exclusive ’ parts include

cubicula

(‘chambers’, despite its old-fashioned ring, is a better translation than the more usual ‘bedrooms’),

triclinia

(‘dining rooms’) and bath suites. This is almost, but not quite, a distinction between public and private areas. Not quite, because – as other Roman writers make clear – all kinds of public business might be conducted

intra cubiculum

, from recitations and dining to (in the case of emperors) judicial trials. It was not, like a modern bedroom, a room from which visitors are almost completely excluded, still less was it used principally for sleeping. It was one to which access was restricted

by invitation

.

He also emphasises a social hierarchy in the design of a house. The Roman elite, those holding public and political office, needed the grand ‘common’ areas of a house. Those lower down the social spectrum could do without a grand vestibule, atrium or

tablinum

(the name given to the relatively large room often found, as in the House of the Tragic Poet, between atrium and peristyle – and used, we guess, by the master of the house). Of course they could do without them. For they did not have a public civic role, with subordinates, dependants and clients to entertain. Quite the reverse: it was they who frequented the vestibules, atria and

tablina

of others.

This theorizing of Vitruvius does not exactly match the evidence from Pompeii. For example, atria are not restricted, as he seems to imply, to the grand display houses, but are found in many very small establishments too. And it can often prove hard to pin the names that Vitruvius uses for individual rooms to the remains we find on the ground (although modern plans tend to be littered with his Latin terminology). Vitruvius was offering an ideal of Roman architecture at its highest and most abstract level, and certainly did not have the houses of a small southern Italian town in mind. Nonetheless, his overall view of the public purpose of the

domus

can help us get a better understanding of at least the more showy houses at Pompeii.

Whether or not the porter actually allowed you access (walking in completely ‘uninvited’ is, I am sure, a more theoretical than real proposition), the interiors of houses were made

to be seen

. Of course, they were closed up and forbidding by night, and even by day the view towards the heart of the house might sometimes have been blocked by screens, internal doors and curtains. But this does not detract from the underlying logic of their plan: that the open front door should offer a carefully designed vista into the interior space. Peering into the House of the Tragic Poet, for example, your eye was drawn first to the large show room between the atrium and the peristyle (Vitruvius’

tablinum

), then through the peristyle directly on to the shrine on the back wall of the garden. Out of vision were the more ‘exclusive ’ areas, such as the large room that was probably a dining room off the peristyle, as well as the service areas and kitchen.

In the House of the Vettii, more imaginative effects were contrived, on a ‘priapic’ theme which has often captured the interest of modern visitors. In the vestibule of this house is one of the most photographed and reproduced images to have been found at Pompeii: a painting of the god Priapus, divine protector of the household, weighing his huge phallus against a bag of money (Ill. 36). There was a more learned point here than might first meet the eye, for as well as showing off a boastful erection, the image also cleverly visualises a pun on the words

penis

and

pendere

, ‘to weigh’. But he was not the only such figure in the house. In the ancient visitor’s line of vision this Priapus was most likely linked to another priapic image. Looking ahead from the front door, through the atrium, to the peristyle and garden (there was no

tablinum

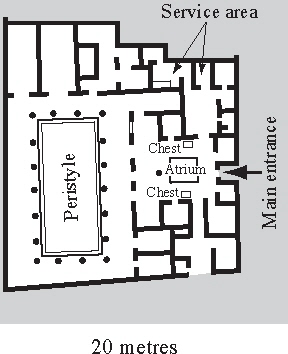

in the House of the Vettii) the eye was drawn to a large marble fountain statue of Priapus, rhyming with the figure in the entranceway – though in this case the joke was that a stream of water spurted out of his erect penis. The implied message of power and prosperity was reinforced by the layout of the atrium itself. On either side large bronze chests – to hold the kind of riches that the Priapus at the doorway is weighing out – were on prominent display. Out of direct vision, were the more ‘exclusive’ zones and the service quarters.

Figure 7

. The House of the Vettii. A large peristyle garden dominates the House of the Vettii, and the most lavishly decorated rooms open onto it. Visitors entering the house looked through to this, past the chests that symbolised (and, no doubt, literally contained) the owners’ wealth.

Again taking their cue from Vitruvius, who related the design of the house to the hierarchies of Roman society (and especially to the relations between men of the elite and their various dependants), archaeologists have re-imagined how one characteristic Roman social ritual might have taken place in this Pompeian setting. That ritual is the early morning

salutatio

, at which ‘clients’ of all sorts would call on their rich patrons, to receive favours or cash in return for their votes, or for providing more symbolic services (escort duty, or simply applause) to enhance the patron’s prestige. From Rome itself, we have plenty of complaints about this from the client’s point of view in the poetry of Juvenal and Martial, who – as relatively well-heeled dependants – predictably enough made the most noise about the indignities they had to suffer in return for a modest handout. ‘You promise me three

denarii,

’ moans Martial at one point, ‘and tell me to be on duty in your atria, dressed up in my toga. Then I’m supposed to stick by your side, walk in front of your chair, while you go visiting ten widows, plus or minus ...’ In Pompeii, it is easy to imagine how such a social ritual might have taken place within the

domus

: the clients lined up outside on those stone benches, then – when the house doors were opened first thing in the morning – they made their way through the narrow entrance passage, into the atrium, to wait their turn to speak to their patron proudly sitting in his

tablinum

, dispensing favours, or not, as the mood took him.