Pompeii (33 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

61. In the nineteenth century, the paintings of the

macellum

were among the most admired in the whole town. This part of the decoration particularly captured the visitors’ imagination, as the woman was identified as a female painter holding a palette. In fact she was carrying an offering dish, as used in sacrifices.

Paintings and sculptures can bring these mute instruments of craft to life, or at least show them in use. We have already seen plenty of buying and selling going on (from bread to shoes) in the paintings of life in the Forum. Another celebrated series of tiny painted friezes from one of the entertainment rooms in the House of the Vettii shows some charming cupids (or kitsch, for those who would detect nouveau riche taste here) engaged in all kinds manufacturing activities. Some are busy at wine-making, others at fulling and perfumery. Some appear to be employed in the garland-making business (another commercial use for flowers). Others are producing jewellery and large bronze vessels in what seems to be a metal-working shop (Plate 20). This is an activity also vividly depicted on a marble plaque, which may once have been a shop sign, albeit a rather more elegant one than usual. It shows bronze- or coppersmiths at work – or so it would seem from the finished products on display in the background – focusing on three stages of the production process. On the left a man is weighing out the raw material on a large balance (and refusing to be distracted by junior, who is demanding attention behind). In the middle, one of the men is about to hammer the metal on an anvil, while another keeps it in place with a pair of tongs. On the right, a fourth craftsman is putting the final details on a large bowl. And you could want for no better illustration than this of the ubiquity of dogs in Pompeii. Although it looks disconcertingly like a platypus as it is rendered here, the creature crouched on a shelf above the head of the last worker can only be a guard-dog.

62. This sculpture nicely evokes the atmosphere of a metal workers’ shop. In addition to the men at work, the scene is completed by a young child and a watching dog. Behind the finished products are on display.

Plenty of written material, whether in graffiti or more formal notices and memorials, adds to the picture, or reminds us of occupations that have not left behind such distinctive traces. If you count up all those mentioned in this way (not including such well-known trades as potter or metal-worker not explicitly mentioned in writing), you get to more than fifty ways of making a living in Pompeii: from weaver to gem-cutter, from architect to pastry cook, from a barber to an ex-slave woman called Nigella, who is described on her tomb as a ‘public pig-keeper’ (

porcaria publica

). Apart from her, women are not mentioned in very great numbers, though they are found in sometimes unexpected contexts. One, named Faustilla, was what we would call a small-time pawnbroker. Three graffiti survive where her clients have written down what they borrowed, the interest they paid (running roughly at the rate of 3 per cent per month), and in two cases what they left as surety – a couple of cloaks and a pair of ear-rings.

It is much trickier to match up these trades to the remains on the site. It is only in a very few types of activity, such as baking or fulling, that permanent installations often allow us to locate a business with certainty. For most of the small commercial units lining the streets, without their furniture, fittings and equipment, there is only occasionally enough that is distinctive remaining to help us work out what was once made or sold inside. A graffito (‘Tannery of Xulmus’) has helped us identify a tannery, and reasonable guesswork has pinpointed the mat-weaver and cobbler. In any case, all kinds of trades would have been plied from what look like ordinary houses. Faustilla would hardly have needed an office. The home base of the painters can be identified only from the cupboard full of paints. And it would have taken only the addition of a couple more looms and slave girls to an atrium to turn weaving for domestic consumption into a commercial enterprise.

That said, there are even more curious gaps in our knowledge. To judge from the profusion of metal implements found all over the town, and the images on the marble plaque and in the paintings at the House of the Vettii, metal-working must have been big business in ancient Pompeii. But all kinds of puzzles remain. We have little idea how they got hold of the raw materials. And so far, apart from a handful of tentatively identified, small-scale workshops and retail outlets (one of which turned up the only known surviving example of a surveyor’s

groma

from the ancient world), only one substantial forge has been discovered, outside the Vesuvius Gate. Perhaps, given the fire risks, this was largely an out-of-town trade. The same must be true of the pottery industry. For only two small potters’ premises have been found within the walls, and one of those was a specialist lamp-maker.

For the rest of this chapter, we shall turn to explore just three examples of the commercial life of Pompeii where it is possible to match up the trade with the place – and, almost, with the face of the person concerned: a baker, a banker and a

garum

maker.

A baker

Between the House of the Painters at Work and the main thoroughfare of the Via dell’Abbondanza stood a large bakery that has only recently been completely uncovered. Bakers were a common sight on the streets of Pompeii. More than thirty baking establishments are known in the city. Some undertook the whole process of production: they milled the grain, baked the bread and sold it. Others, to judge from the absence of milling equipment, produced loaves from ready-prepared flour. Though there are some curious clusters (in one road just to the north-east of the Forum there were seven bakeries in just over 100 metres), they were found all over the city, so that no Pompeian was ever far from a bread supply. Besides, bread could also be sold in temporary street stalls and, no doubt, by home delivery on a donkey or mule (Ill. 25, 64).

This bakery on the Via dell’Abbondanza combined milling and baking – and, maybe, other entertainment functions (Fig. 15). It was a two-storey property, with a balcony across part of the frontage above the street. Unusually for Pompeii, considerable parts of the flooring of the upper level have been found and preserved just as it had collapsed into the rooms below – a triumph of archaeological conservation it is true, but a feature that makes it harder for any casual observer to work out the layout and appearance of the place as a whole. At the corner of the property was one of the many street or crossroads shrines we find in the city: a rough-and-ready altar perched on the pavement, with a painting of a religious sacrifice plastered on its outside wall above.

One door from the main street led into the bakery itself, the other (next to the altar) into a reasonably sized two-roomed shop. On the ground floor these appear to be entirely separate units, but the placing of the stairways to the upper floor suggests that the whole property interconnected above. It was all presumably under a single proprietor, even if we must imagine something other than bread being on sale in the shop (for, in that case, they would surely have made a direct connection between the retail unit and the place next door where the bread was made). There was also a side entrance leading into a stable from the alleyway that ran up from the Via dell’Abbondanza, between this complex and the large House of Caius Julius Polybius. This was the alleyway where, as we saw in Chapter 2, the cesspits collecting the latrine waste had been dug up and cleaned out just before the eruption, the piles of refuse still on the ground beside them.

Entering the bakery by the main door, you went into a large vestibule, from which one of several wooden staircases climbed to the upstairs rooms. To judge from the graffiti on the left-hand wall, consisting mostly of numerals, it was here that some of the trade was carried out – checking out consignments of bread, or perhaps even selling it to customers. Any caller would certainly have been able to see and hear the baking at work, for the main oven – rather like a big wood-burning pizza oven in modern Italy – stood just a few metres further in (Ill. 63). On the left was the large room where the dough was prepared. A window had been inserted to bring some light from the outside onto the mixers and kneaders who mixed up the dough in large stone bowls or worked it into shape at a wooden table (the wood does not survive, but the masonry supports which carried it do). It must have been hot work, in a dingy environment. But there had been some attempt to brighten it up: on one wall there was a painting of a naked Venus, admiring herself in a mirror. It is hard not to think of a pin-up in a modern factory.

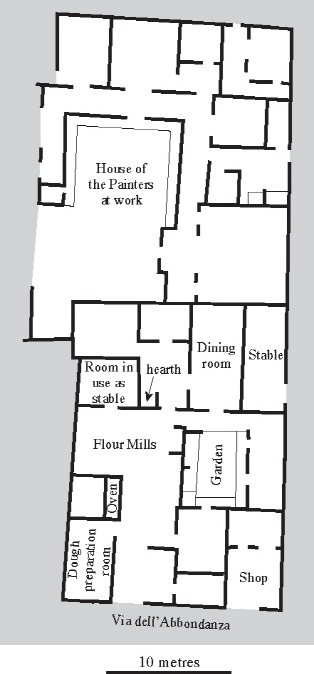

Figure 15

. The Bakery of the Chaste Lovers. A commercial bakery doubling as a catering business. At least the dining room (

triclinium

) here is so large that it almost certainly was used by people other than the baker and his family. At the time of the eruption two rooms on the premises were in use as stables.

63. The large bread oven from the Bakery of the Chaste Lovers. Somewhat dilapidated, it still shows the cracks caused by the earthquake of 62 and the tremors that no doubt preceded the eruption.

When the dough was ready and shaped into loaves, they passed it through a little hatch at the end of the room directly to the area in front of the oven. Occasionally, the individual maker might even have stamped his work. Several carbonised loaves have been found in Herculaneum, for example, imprinted with the words ‘Made by Celer, the slave of Quintus Granius Verus’ – and very likely some or most of the workers in our bakery would have been slaves too. From the other side of the hatch, the bread would have been loaded onto trays, baked, then removed for storage or sale.

This particular oven had seen better days. One large crack in its structure had been patched up and plastered over some time before the eruption – no doubt after the big earthquake of 62 CE. But further cracks had since appeared, probably thanks to the quakes and tremors in the days and weeks running up to the eruption, and repair work was underway throughout the property. The oven was probably still operating, though on a reduced scale. Sadly, there was no dramatic discovery here like the one made at another bakery in the mid nineteenth century. Eighty-one loaves were discovered still firmly shut in the oven, almost 2000 years overcooked. These are round in shape, and divided into eight sections, just as we sometimes see them in paintings (Ill. 64).