Pompeii (35 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The sum of 520

sesterces

for a mule sold to Marcus Pomponius Nico, previously slave of Marcus: money which Marcus Cerrinius Euphrates is said to have received according to the terms of the contract with Lucius Caecilius Felix. The aforementioned sum Marcus Cerrinius Euphrates, previously slave of Marcus, declared that he had received, paid down, from Philadelphus, slave of Caecilius Felix. (Sealed).

Transacted at Pompeii, on the fifth day before the kalends of June [28 May], in the consulship of Drusus Caesar and Gaius Norbanus Flaccus [15 CE]

The auction records of Jucundus himself do not always specify exactly what had been bought and sold. In most cases they refer simply to ‘the auction of’, with the name of the seller. But we do find him on a couple of occasions referring to the sale of slaves. In December 56 CE, a woman called Umbricia Antiochis received 6252

sesterces

after the sale of her slave Trophimus. This particular slave was obviously a valuable commodity, raising more than four times as much as another slave who was sold for just over 1500

sesterces

a couple of years earlier. To see this as roughly three times the cost of that mule is an unsettling reminder of the ‘commodification’ of human beings that lay at the heart of Roman slavery, for all the expectations of eventual freedom that a Roman slave might have. Jucundus is also known to have sold some ‘boxwood’ (a wood commonly used for writing tablets – but not these, which are of pine) for almost 2000

sesterces

, and a quantity of linen, the property of one ‘Ptolemy, son of Masyllus, of Alexandria’; this is another nice example of an import from overseas and of a foreign trader, though sadly the price raised does not survive.

In general, Jucundus is neither dealing in very large amounts of money nor operating at the very bottom of the range. The largest sum raised at any of his recorded auctions is 38,079

sesterces

. Whatever the objects of this sale were (it appears simply as ‘the auction of Marcus Lucretius Lerus’), they went for more than five times the likely annual turnover of the smallholding we looked at earlier in this chapter. Yet across the archive as a whole there were only three payments over 20,000

sesterces

, just as there were only three under 1000. The median amount is around 4500

sesterces

. Jucundus’ commission seems to have varied. In two of the tablets it is stated to be 2 per cent. In most cases we can only guess from the final figure paid over to the seller what the likely commission had been – and that is sometimes as much as 7 per cent. Whether Jucundus would have become well off on this depends entirely on how many auctions he conducted, and for what value of goods.

But the auctions were not his sole source of income. The other set of sixteen documents concerns his business contracts with the town administration itself. As was usual in the Roman world, the local taxes of the city of Pompeii were farmed out for private contractors to collect (taking a profit themselves, of course). For part of his career, at least, Jucundus was involved in collecting at least two taxes: a market tax, probably levied on stallholders; and a grazing tax, probably levied on those who made use of publicly owned pasture land. Among his documents we find several receipts for these: 2520

sesterces

per year for the market tax, 2765 for the grazing tax (sometimes paid in two instalments). He also rented, and presumably worked or sublet, properties that were in public ownership. One was a farm, at an annual rental of 6000

sesterces

. This rent seems to have been at the limit of what Jucundus could afford – at least if cashflow, rather than inefficiency, was the cause of him being in arrears from time to time. The other was a fullery (

fullonica

), for which he had to find 1652

sesterces

per year.

It is striking to see here again the economic role of the local government, not merely raising taxes but also owning property in the town and surrounding countryside, which was then rented out for profit. An ‘ancestral farm’, as the documents describe it, is perhaps not surprising. But quite how the city came to own a fullery is a mystery. So much of a mystery, in fact, that some historians have suspected that

fullonica

here does not mean ‘fullery’, but a ‘tax on fulling’. This was, in other words, another of Jucundus’ tax-collecting businesses, not evidence of his further diversification into the textile and laundry trade. Who knows? But whatever the details of these and other properties (Jucundus can hardly have been the city’s only tenant), the tablets do give us a clue about the organisation of these affairs from the city’s side. The documents show that this day-to-day management of the public assets of the town was not in the hands of an elected official from the city’s elite, but of a public slave – or as the documents sometimes officially entitle him, a ‘slave of the colonists of the

colonia Veneria Cornelia

’. Two of these are mentioned in Jucundus’ tablets: the first was called Secundus, who received the farm rental in 53 CE; he was presumably replaced by Privatus, who received all the later payments.

Together, the buyers and sellers, the servants and officials, and (most numerous of all) the witnesses listed give us the names of some 400 residents of Pompeii around the middle of the first century CE. These range from the public slaves to Cnaius Alleius Nigidius Maius, one of the leading members of the local political elite and owner of the large property for rent we explored in Chapter 3, who turns up as a witness to one of Jucundus’ auction documents. Even a quick glance at the archive shows the concern with status that underpinned social and business relations all over the Roman world. When they appear in the documents, the slaves are clearly referred to as slaves, with the name of their owners specified; likewise the ex-slaves. Not so obvious at first sight is the ordering of the lists of witnesses. But careful recent analysis has shown without much doubt that on each occasion the witnesses’ names were recorded in order of their social prestige. In the one list in which Nigidius Maius occurs, for example, he takes first place. On two occasions, those nice calibrations of order were disputed, or at least had to be revised. In two lists, the writer had taken the trouble to rub out (or more correctly scrape out) a name and change the hierarchy.

Nonetheless, for all their emphasis on rank, the tablets suggest a mixed society of buying and selling, borrowing and lending, at Pompeii. Bottom of the list though they may have been, ex-slaves were acting as witnesses to the same transactions as members of the oldest, and most elite, families in the town. Women were in evidence too. They did not act as witnesses. But out of the 115 other names preserved on the tablets, fourteen are women’s. They are all sellers at auction (one the seller of the slave, Trophimus). This is not a large proportion of course, but it still suggests that women were more ‘visible’ in the commercial life of the early Roman empire than some of the gloomier modern accounts of their role and standing would have us believe.

Of Caecilius Jucundus himself we know relatively little apart from what is in the documents. The usual assumption (and it is not much more than that) is that he was the descendant of a slave family, though freeborn himself. We do not know where his auctions took place, or whether he operated from an ‘office’ separate from his house. That house, however, can tell us a little more. It was large and richly painted, which are the clearest signs that his business was profitable. The decoration included a large wild-animal hunt on the garden wall, long faded beyond recognition; a painting of a couple making love, now in the Secret Cabinet of the Naples Museum, but once in the colonnade of the peristyle (a touching or slightly vulgar display, depending on your point of view); an implausibly benign guard dog rendered in mosaic by the front door; and those famous marble relief panels which appear to depict the earthquake of 62 (Ill. 5).

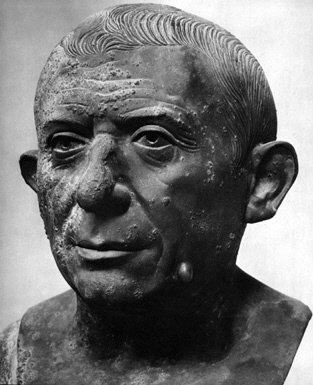

It is just possible too that we have a portrait of him. In the atrium of the house, two squared pillars (or herms) were found, of a type commonly used in the Roman world to support marble or bronze portrait heads. In the case of male portraits, genitals would be attached half way down the herm, making what is, to be honest, a rather odd ensemble. On one of these pillars genitals and bronze head survived – a highly individualised portrait of a man, with thinning hair and a prominent wart on his left cheek (Ill. 68). Both pillars carry exactly the same inscription: ‘Felix, ex-slave, set this up to the our Lucius’. What the exact relationship was between this Felix and Lucius and the Lucius Caecilius Felix and Lucius Caecilius Jucundus of the tablets we do not know. The Felix on the herm might be the banker, or he might be an ex-slave of the family with the same name. The Lucius Caecilius Jucundus of the tablets might have nothing to do with this statue at all. But, although archaeologists sometimes insist on grounds of style that the portrait must be earlier than the middle of the first century CE, it is not completely inconceivable that this down-to-earth-looking character is none other than our auctioneer, middle-man and moneylender.

The tablets of Caecilius Jucundus are not the only such written records to be found in the town. In 1959 just outside Pompeii, another large cache of documents from the first century CE were discovered. They detailed all kinds of legal and business transactions at the port of Puteoli – contracts, loans, IOUs and guarantees – involving a Puteolan family of ‘bankers’, the Sulpicii. How the tablets ended up near Pompeii, some 40 kilometres away from Puteoli across the Bay of Naples, we can only guess.

One particularly intriguing find from Pompeii itself is a couple of wax tablets discovered stashed away with some silverware in the furnace of a set of baths. These record a loan from one woman, Dicidia Margaris, to another, Poppaea Note, an ex-slave. As guarantee of her loan Poppaea Note handed over two of her own slaves, ‘Simplex and Petrinus or whatever names they go under’. If she did not repay the loan by 1 November following, then Dicidia Margaris was allowed to sell the slaves to recover the money ‘on the ides [13th] of December ... in the Forum at Pompeii in broad daylight’. Careful arrangements were stipulated in case the slaves were to raise more or less than the sum owed. Again, it is striking to see a business arrangement between two women (though in this case Dicidia Margaris is represented by her male guardian). It is striking also to see slaves parcelled up, as it were, and handed over as living surety. But more curious is the date of the document. These arrangements were dated 61 CE, but the tablets were obviously still thought important enough to be hidden away for safekeeping along with the family silver, eighteen years later. Why? Was there perhaps still some on-going dispute about the repayment of the loan, or the sale of the slaves – and one of the women thought they might still need the written agreement?

Inevitably, this raises the question of the levels and uses of literacy in Pompeii. It is very easy to get the impression that the city was a highly literate, even cultured place. More than 10,000 pieces of writing, most in Latin, but some in Greek or Oscan, and at least one in Hebrew, have been recorded there. Election posters, graffiti and all kinds of notices – price lists, advertisements for gladiatorial games, shop signs – cover the walls. Much of the graffiti is of a familiar kind, from pleas for help (‘A bronze jar has gone from this shop. Reward of 65

sesterces

for anyone returning it’) to laddish boasts (‘Here I fucked loads of girls’). But some of it conveys a more highbrow impression. We find, for example, over fifty quotations or adaptations from well-known classics of Latin literature, including lines of Virgil, Propertius, Ovid, Lucretius and Seneca, not to mention a snatch of Homer’s

Iliad

(in Greek). There are also many other snatches of poetry, either original compositions from some Pompeian versifier or part of a more popular repertoire.

68. Found in the House of Caecilius Jucundus, this bronze portrait may be the banker himself or perhaps, more likely, one of his extended family or ancestors. Either way, it is a vivid image of a middle-aged Pompeian, warts and all.

Modern students of Latin who have been puzzled by that strange genre of Roman love poetry, which imagines the lover locked outside his girlfriend’s house, addressing his words of anguish to the closed door, will be amused to find just such a poem in Pompeii, actually written up in a doorway:

Would I might hold around your neck my arms entwined

And place kisses on your lovely lips ... etc.

Critics have judged it a rather feeble poetic effort, probably a compilation of various misremembered lines of verse into a not entirely satisfactory whole. They have, moreover, found it hard to decide whether to take literally (or as further evidence of a botched job) the fact that the poem appears to be written

by

a woman

to

a woman.