Pompeii (7 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Given the tricky evidence, there is an unusual amount of agreement about the main lines of the history it reveals. Most people accept that, as the city’s plan suggests, the original nucleus of the settlement was in the south-west corner, where the irregular pattern of streets points to something that archaeologists have rather grandly called the ‘Old Town’. But, beyond that, the number of early finds, both pottery and the evidence of buildings, from all over the town has made it increasingly clear that Pompeii was already a relatively widespread community within the walls in the sixth century BCE. In fact there is hardly anywhere in the city where deep digging under the existing structures has not produced some traces of sixth-century material, albeit in tiny fragments and sometimes the product of especially keen searching (one story being that Amadeo Maiuri, the ‘Great Survivor’, who directed the excavations on the site from 1924, through fascism and the Second World War, up until 1961, used to give his workmen a bonus if they found early pottery where he hoped – an archaeological tactic that usually produces results). It is also clear that there is a dramatic falling off in finds through the fifth century, a gradual build-up again through the fourth, until the third century marks the start of the recognisable urban development as we now see it.

There is much less agreement about exactly how old the original nucleus is, and whether the occasional finds of material on and near the site from the seventh, eighth or even ninth centuries BCE represent a settled community as such. And there are sharp differences of opinion about how the area within the walls was used in the sixth century BCE. One view holds that it was mostly enclosed farmland, and that our finds come from isolated agricultural buildings or cottages or rural sanctuaries. This is not implausible, except for the unconvincingly large number of ‘sanctuaries’ that this view seems to produce – some of them much less obviously religious sites than the ‘Etruscan column’.

A more recent and rival position sees a much more developed urban framework, even at this early date. The main argument for this is that, so far as we can tell from the now scanty traces, all the early structures outside the ‘Old Town’ were built following the later, developed alignment of the streets. This does not mean that sixth-century Pompeii was a densely occupied town in our sense. In fact, even in 79 CE there was plenty of open, cultivated land within the circuit of the walls. But it does imply that the street grid was already established, at least in some rudimentary form. On this interpretation Pompeii was at that point a city already ‘waiting to happen’ – even if there was an uncomfortably long three centuries before that ‘happening’ was to come about

Equally debated is the question of who these early Pompeians were. It is not only the town’s latest phases that have a decidedly multicultural tinge, with their Greek art, Jewish dietary rules, Indian bric-a-brac, Egyptian religion and so forth. Even in the sixth century BCE Pompeii stood at the heart of a region – known, then and now, as Campania – where, long before the Romans came to dominate, indigenous peoples speaking the native Oscan language rubbed shoulders with Greek settlers. There had, for example, been a substantial Greek town at Cumae, fifty kilometres away across the Bay of Naples, since the eighth century BCE. Etruscans too were a significant presence. They had settled in the region from the middle of the seventh century, and for 150 years or so rivalled the Greek communities for control of the area. Which of these groups was the driving force behind the early development of Pompeii is frankly anyone’s guess, and archaeology does not provide the answer: a fragment of an Etruscan pot, for example, almost certainly shows contact between the inhabitants of the town and the Etruscan communities of the area, but it does not demonstrate (despite some confident assertions to the contrary) that Pompeii was an Etruscan town.

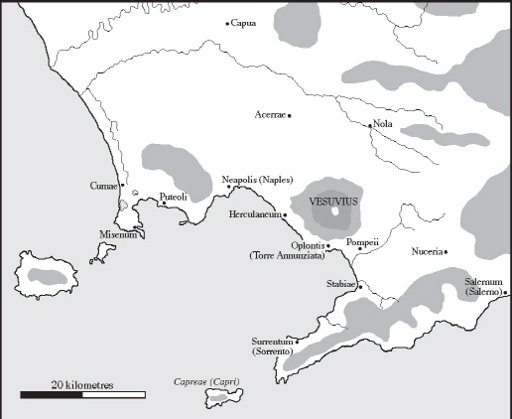

Figure 4.

Map of area surrounding Pompeii

What is more, ancient writers seem to have been no more certain than we are about how to disentangle the city’s earliest history. Some relied on marvellously inventive etymologies, deriving the name ‘Pompeii’ from the ‘triumphal procession’ (

pompa

) of Hercules, who was supposed to have passed this way after his victory over the monster Geryon in Spain, or from the Oscan word for ‘five’ (

pumpe

), so inferring that the town had been formed out of five villages. More soberly, the Greek writer Strabo, first-century-BCE author of a multi-volume treatise on

Geography

, offered a list of the town’s inhabitants. At first sight this matches up reassuringly with some of our own theories: ‘Oscans used to occupy Pompeii, then Etruscans and Pelasgians [i.e. Greeks]’. But whether Strabo had access to good chronological information, as more optimistic modern scholars have hoped, or whether he was just hedging his bets in the face of uncertainty, as I tend to feel, we simply cannot be sure.

Strabo did not, however, stop with the Pelasgians. ‘After that,’ he wrote, ‘it was the turn of the Samnites. But they too were ejected.’ Here he was referring to the period between the fifth and third centuries BCE, when Pompeii began to take its familiar form. These Samnites were another group of Oscan-speakers, tribes from the heartlands of Italy, who feature in later Roman stereotypes – not entirely unfairly – as a tough race of mountain warriors, hard-nosed and frugal. In the shifting geopolitics of pre-Roman Italy, they moved into Campania and managed to establish control of the region, decisively defeating the Greeks at Cumae in 420 BCE, only fifty years after the Greeks themselves had managed to get rid of the Etruscans.

It is perhaps this series of conflicts that accounts for the apparent change in Pompeii’s fortunes in the fifth century. In fact some archaeologists have concluded from the more or less complete absence of finds on the site at that point that the town was abandoned for a time. But only for a time. By the fourth century BCE, Pompeii was probably – though firm evidence for this, beyond Strabo himself, is virtually nil – part of what is now grandly known as a ‘Samnite Confederacy’. At least, in a key position on the coast and at the mouth of the river Sarno (whose precise ancient course is hardly better known to us than the shoreline), it acted as the port for the settlements upstream. As Strabo noted, hinting at yet another derivation of the town’s name, it was located near a river which served to ‘take cargoes in and

send them out

(Greek:

ekpempein

)’.

‘But the Samnites too were ejected’? Strabo had no need to explain who was behind the ejection. For this was the period of Rome’s expansion through Italy, and of its transformation from a small central Italian town with control over its immediate neighbours to the dominant power in the entire peninsula and increasingly in the Mediterranean as a whole. In the second half of the fourth century BCE Campania was just one of the fields of operation in a series of Roman wars against the Samnites. Pompeii had its own cameo role in these, when in 310 BCE a Roman fleet landed there and disembarked its troops, who proceeded to ravage and plunder the countryside up the Sarno valley.

These wars involved many of the old power bases of Italy: not just Rome and various tribes of Samnites, but Greeks now concentrated in Naples (Neapolis) and, to the north, Etruscans and Gauls. And they were not a walkover for Rome. It was at the hands of the Samnites, in 321 BCE, that the Roman army sustained one of its most humiliating defeats ever, holed up in a mountain pass known as the ‘Caudine Forks’. Even the Pompeians put up a good fight against the plunderers from the Roman fleet. According to the Roman historian Livy, as the soldiers laden with their loot had almost made it back to the ships, the locals fell upon them, grabbed the plunder and killed a few. One small victory for Pompeii against Rome.

But the Romans – as was always the way – won in the end. By the early third century BCE, Pompeii and its neighbours in Campania had been turned, like it or not, into allies of Rome. These allies retained more or less complete independence in their own local government. There was no concerted attempt to impose on them Roman-style institutions, nor to demand the use of Latin rather than their native Italic language. The main language of Pompeii continued to be Oscan, as it had been under the Samnites. But they were obliged to provide manpower for the Roman armies and to toe the Roman line in matters of war, peace, alliances and the rest of what we might anachronistically call ‘foreign policy’.

In many ways Pompeii did very well out of this dependent status. From the end of the third century, the population of the town increased dramatically, or so we conclude from the tremendous expansion of housing. In the second, an array of new public buildings were erected (baths, gymnasium, temples, theatre, law courts), while the House of the Faun is only the largest of a number of grand private mansions that made their permanent mark on the urban scene at this period. It was now that Pompeii, for the first time, began to look like what we would call ‘a town’. Why?

One answer may be Hannibal’s invasion of Italy at the end of the third century. As the Carthaginians pressed south from their famous crossing of the Alps, Campania became once again a major arena of fighting – some communities remaining loyal to Rome, others defecting to the enemy. Capua to the north was one of those which defected, and it was in turn besieged by the Romans and dreadfully punished. Nuceria, on the other hand, just a few kilometres from Pompeii, remained loyal and was destroyed by Hannibal. Even if it can hardly have remained entirely unscathed in the middle of this war zone, Pompeii was not directly hit and must have been a likely refuge for many of those displaced and dispossessed in the conflict. This may well account for some of the striking growth in housing at this period, and the spurt in urban development. The town, in other words, was an unexpected beneficiary of one of Rome’s darkest hours.

Another answer is the onward expansion of Roman imperialism in the east and the wealth that came with it. Even if the allies were not free agents in Rome’s wars of conquest, they certainly took some share in the profits. These came partly from the spoils and booty of the battlefield, but also from the trading links increasingly opened up with the eastern Mediterranean and the new avenues of contact with the skills and artistic and literary traditions of the Greek world (beyond those offered by the Greek communities that still remained in the local area).

At least one plundered showpiece, captured when the Romans and their allies sacked the fabulously rich Greek city of Corinth in 146 BCE, seems to have been on display outside the temple of Apollo in Pompeii. What exactly it was we do not know (a statue, perhaps, or luxury metalwork), but the inscription in Oscan recording its gift by the Roman commander, Mummius, on that occasion still survives. Further afield, family names found at Pompeii are recorded also in the great Greek trading centres, such as the island of Delos. It is impossible to be absolutely certain that any of the individuals concerned were actually native Pompeians. Nonetheless, the impact of trading contacts like these is clear to see – right down to the daily bread and butter of (at least) the Pompeian elite. Carefully collecting seeds and the microscopic traces of spices and other foodstuffs, archaeologists exploring a group of houses near the Herculaneum Gate have suggested that, from the second century on, the inhabitants were enjoying a more varied diet, drawn from further afield, including a good sprinkling of pepper and cumin. And even if the House of the Faun was hardly a typical Pompeian residence, its array of mosaics – especially the

tour de force

that was the Alexander mosaic – attest to the high level of Greek artistic culture that could be found in the city.

In short, second-century BCE Pompeii was an expanding and thriving community, doing very nicely out of its relations with Rome. But, though allies, the Pompeians were not Roman citizens. For the privileges of that status, and to become a truly Roman town, they had to resort to war.

Becoming Roman

The so-called ‘Social War’ broke out in 91 BCE, when a group of Italian allies (or

socii

, hence the name) went to war with Rome. Pompeii was one of them. It now seems a peculiar kind of rebellion. For, although the allied motives have been endlessly debated, it is most likely that they resorted to violence, not because they wished to turn their back on the Roman world and escape its domination, but because they resented not being full members of Rome’s club. They wanted, in other words, Roman citizenship, and the protection, power, influence and the right to vote at Rome itself which went with it. It was a conflict notorious for its savagery, and in effect – given that Romans and allies had become used to fighting side by side – a civil war. Predictably enough, the vastly superior force of Romans was victorious in one sense, but the allies were in another: for they got what they wanted. Some of the rebel communities were bought off instantly by the offer of citizenship. But even those who held out were enfranchised once they had been defeated in battle. From then on, for the first time, more or less the whole of the peninsula of Italy became Roman in the strict sense of the word.