Prayers of Agnes Sparrow

Read Prayers of Agnes Sparrow Online

Authors: Joyce Magnin

Agnes Sparrow

The Prayers of Agnes Sparrow

Copyright © 2009 by Joyce Magnin

ISBN-13: 978 -1- 4267-0164-1

Published by Abingdon Press, P.O. Box 801, Nashville, TN 37202

www.abingdonpress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form,

stored in any retrieval system, posted on any website, or

transmitted in any form or by any means—digital, electronic,

scanning, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written

permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in

printed reviews and articles.

The persons and events portrayed in this work of fiction are the

creations of the author, and any resemblance to persons living or

dead is purely coincidental.

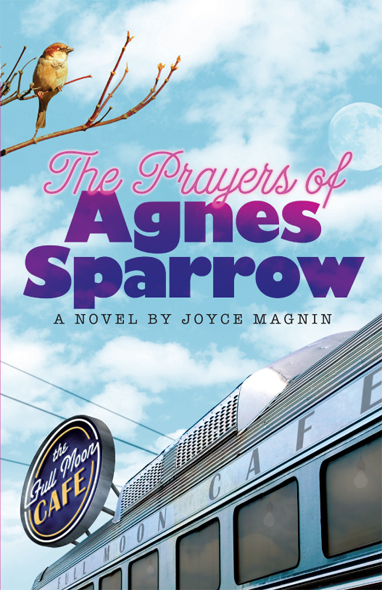

Cover design by Anderson Design Group, Nashville, TN

Author photo by Emily Moccero

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moccero, Joyce Magnin.

The prayers of Agnes Sparrow / Joyce Magnin.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4267-0164-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

I. Title.

PS3601.L447P73 2009

813’.6—dc22

2009014854

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 / 14 13 12 11 10 09

For my sister, Barbara

Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written without the love and support of:

Pam Halter, my dear friend who kept listening and reading from the very first word.

The Writeen Crue: Pam, Tim, Dawn, Candy, Dale, Rosemarie, Winnie, Floss, Brenda, and especially Nancy Rue, who got it where it needed to be.

Lisa Samson who helped me find the heart of the story.

Marlene Bagnull. She never let me quit.

Thank you also to my family for understanding when “Mommy is working!”

Thank you to my wonderful editor, Barbara Scott, who taught me much along the way.

A special thank you to Jean Shanahan and Phoebe Wagner who came through when I really needed them.

And last, but never least, thank you to my mom, Flossie, who showed me that life does not always have to be taken so seriously and that perfect pie is possible.

Even a blind squirrel finds a nut once in a while.

—Ruth Knickerbocker

I

f you get off the Pennsylvania Turnpike at the Jack Frost Ski Resort exit, turn left, and travel twenty-two and one quarter miles, you’ll see a sign that reads: Bright's Pond, Home of the World's Largest Blueberry Pie.

While it is true that in 1961 Mabel Sewicky and the Society of Angelic Philanthropy, which did secret charitable acts, baked the biggest blueberry pie ever in Pennsylvania, most folks will tell you that the sign should read: Bright's Pond, Home of Agnes Sparrow.

October 12, 1965. That was the day my sister, Agnes Sparrow, made an incredible decision that changed history in our otherwise sleepy little mountain town and made her sign-worthy.

“I just can’t do it anymore, Griselda. I just can’t.”

That's what Agnes said to me right before she flopped down on our red, velvet sofa. “It ain’t worth it to go outside anymore. It's just too much trouble for you—” she took a deep breath and sighed it out “—and heartache for me.”

Agnes's weight had tipped a half pound over six hundred, and she decided that getting around was too painful

and too much of a town spectacle. After all, it generally took two strong men to help me get Agnes from our porch to my truck and then about fifteen minutes to get her as comfy as possible in the back with pillows and blankets. People often gathered to watch like the circus had come to town, including children who snickered and called her names like “pig” or “lard butt.” Some taunted that if Agnes fell into the Grand Canyon she’d get stuck. It was devastating, although when I look back on it, I think the insults bothered me more than they did Agnes.

Her hips, which were wider than a refrigerator, spread out over the sofa leaving only enough room for Arthur, our marmalade cat, to snuggle next to her. “I think I’ll stay right here inside for the remainder of the days God has set aside for me.” She slumped back, closed her eyes, and then took a hard breath. It wiggled like Jell-O through her body. I held my breath for a second, afraid that Agnes's heart had given out since she looked so pale and sweaty.

But it didn’t.

Agnes was always fat and always the subject of ridicule. But I never saw her get angry over it and I only saw her cry once—in church during Holy Communion.

She was fourteen. I was eleven. We always sat together, not because I wanted to sit with her, but because our father made us. He was usually somewhere else in the church fulfilling his elder's responsibilities while our mother helped in the nursery. She always volunteered for nursery duty. I think it was because my mother never really had a deep conviction about Jesus one way or the other. Sitting in the pews made her nervous and she hated the way Pastor Spahr would yell at us about our sins, which, if you asked me, my mother never committed and so she felt unduly criticized.

Getting saddled with “fat Agnes” every Sunday wasn’t easy because it made me as much a target of ridicule as her. Ridicule by proximity. Agnes had to sit on a folding lawn chair in the aisle because she was too big to slip into the pew. And since she blocked the aisle we had to sit in the last row.

Our father served Communion, a duty he took much too seriously. The poor man looked like a walking cadaver in his dark suit, white shirt, and striped tie as he moved stiffly down the aisle passing the trays back and forth with the other serious men. But the look fit him, what with Daddy being the town's only funeral director and owner of the Sparrow Funeral Home where we lived.

On that day, the day Agnes cried, Daddy passed us the tray with his customary deadpan look. I took my piece of cracker and held it in my palm. Agnes took hers and we waited for the signal to eat, supposedly mulling over the joy of our salvation and our absolute unworthiness. Once the entire congregation, which wasn’t large, had been served, Pastor Spahr took an unbroken cracker, held it out toward the congregation, and said, “Take. Eat, for this is my body broken for you.” Then he snapped the cracker. I always winced at that part because it made me think about broken Jesus bones getting passed around on a silver platter.

I swallowed and glanced at Agnes. She was crying as she chewed the cracker—her fat, round face with the tiny mouth chewing and chewing while tears streamed down her heavy, pink cheeks, her eyes squinted shut as though she was trying to swallow a Ping-Pong ball. Even while the elders served the juice, she couldn’t swallow the cracker for the tears. It was such an overwhelmingly sad sight that I couldn’t finish the ritual myself and left my tiny cup of purple juice, full, on the pew. I ran out of the church and crouched behind a large boulder at the edge of the parking lot, jammed my

finger down my throat and threw up the cracker I had just swallowed. I swore to Jesus right then and there that I would never let him or anyone hurt my sister again.

Which is probably why I took the whole Agnes Sparrow sign issue to heart. I knew if the town went through with their plan it would bring nothing but embarrassment to Agnes. I imagined multitudes pulling off the turnpike aimed for Jack Frost and winding up in Bright's Pond looking for her. They’d surely think it was her tremendous girth that made her a tourist attraction.

But it wasn’t. It was the miracles.

At least that's what folks called them. All manner of amazements happened when Agnes took to her bed and started praying. It made everyone think Agnes had somehow opened a pipeline to heaven and because of that she deserved a sign— a sign that would only give people the wrong idea.

You see, when my sister prayed, things happened; but Agnes never counted any answer to prayer, yes or no, a miracle. “I just do what I do,” she said, “and then it's up to the Almighty's discretion.”

The so-called Bright's Pond miracles included three healings—an ulcer and two incidents of cancer—four incidents of lost objects being located miles from where they should have been, an occurrence of glass shattering, and one exorcism, although no one called it that because no one really believed Jack Cooper was possessed—simply crazy. Agnes prayed and he stopped running around town all naked and chasing dogs. Pastor Spahr hired him the next day as the church janitor. He did a good job keeping the church clean, except every once in a while someone reported seeing him howling at the moon. When questioned about it, Pastor Spahr said, “Yeah, but the toilets are clean.”

Pastor Rankin Spahr was a solid preacher man. Strong, firm. He never wavered from his beliefs no matter how rotten he made you feel. He retired on August 1, 1968, at the ripe old age of eighty-eight and young Milton Speedwell took his place.

Milton and his wife, Darcy, were fresh from the big city, if you can call Scranton a big city. I suppose he was all of twenty-nine when he came to us. Darcy was a mite younger. She claimed to be twenty-five but if you saw her back then, you’d agree she was barely eighteen.

Milton eventually became enamored with Agnes just like the rest of the town and often sent people to her for prayer and counsel.

But it wasn’t until 1972 when Studebaker Kowalski, the recipient of miracle number two—the cancer healing—that Agnes's notoriety took front seat to practically everything in town. Studebaker had a petition drawn up, citing all the miracles along with a dozen or more miscellaneous wonders that had occurred throughout the years.

“Heck, the Vatican only requires three miracles to make a saint,” he said. “Agnes did seven. Count ’em, seven.”

Just about everyone in town—except Agnes, Milton Speedwell, a cranky old curmudgeon named Eugene Shrapnel, and me—added their signatures to the petition making it the most-signed document ever in Bright's Pond. Studebaker planned to present it to Boris Lender, First Selectman, at the January town meeting.

Town meetings started at around 7:15 once Dot Handy arrived with her steno pad. She took the minutes in shorthand, typed them up at home on her IBM Selectric, punched three holes in the sheet of paper, and secured it in a large blue binder that she kept under lock and key like she was safekeeping the secret formula for Pepsi Cola.

That evening I settled Agnes in for the night and made sure she had her TV remote, prayer book, and pens. You see, Agnes began writing down all of the town's requests when it became so overwhelming she started mixing up the prayers.

“It's all become prayer stew,” she said. “I can’t keep nothing straight. I was praying for Stella Hughes's gallbladder when all the time it was Nate Kincaid's gallbladder I should have asked a favor for.”