Prisoners of the North (4 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

In Swiftwater, who owned a piece of No. 13 and who went on to lose more than one fortune, Boyle had a willing instructor. Each in his own way was a man of vision, but Boyle differed from the prospector. Gates, who owned the only starched shirt collar in town and went to bed rather than be seen without it, was a man who loved to watch himself lampooned on the stage of the Monte Carlo by Gussie Lamore’s sister Nellie and revelled in his new sobriquet, the Knight of the Golden Omelette. Boyle had neither the time nor the inclination for that kind of frolic. He thought in terms of gigantic nozzles ripping up the overburden from the verdant valleys, and of enormous floating machines clawing their way to bedrock.

One characteristic of the Boyle style was the speed with which he made up his mind and moved, often under appalling conditions. He threw himself into each new venture with all the enthusiasm of a small boy playing his first game of Parcheesi. Life to Boyle

was

a game. For him, it was always the race that counted, not the gold and certainly not the prestige. As a born leader, he needed to be first off the mark, ahead of the pack—determined to win.

He could not idle away the Yukon winter. He needed a hydraulic and timber concession eight miles long, from rim to rim of the Klondike Valley, before someone else could beat him to it. For that he had to go to Ottawa, so he signed the necessary documents and left Slavin to work out the application to the Gold Commissioner while he headed for the Outside before freeze-up. Less than two months after he landed in Dawson he was ready to make his move.

While thousands of men and women were struggling to reach the city of gold in the face of impossible natural obstacles, here was Boyle headed the other way. To live in Dawson in that first gold-rush winter was akin to living on the moon. For most there was no escape. Only the hardiest, the hungriest, or the craziest dared attempt the daunting journey to the Outside. But Boyle and Swiftwater Bill Gates were planning to do just that. As they set off in Boyle’s collapsible boat, clinging to the eddies along the Yukon riverbank and inching their flimsy craft forward against a current that could reach seven miles an hour, winter was already setting in and pack ice was forming all about them. When Boyle’s eccentric partner (who insisted on wearing a colourful four-in-hand tie beneath his furs) broke through the thin crust at one point, Boyle dragged him, soaking wet, to safety. The craft was just as vulnerable: the collapsible boat kept collapsing and had to be repaired three times before the pair abandoned it at Carmacks Post, 250 miles upriver from Dawson. There they came upon a huddle of men and horses about to give up and return to the Klondike, and it was then that Boyle’s qualities of leadership were tested. At his suggestion, the group agreed to pool their resources and travel together under his command. They called him Captain, a title that certainly fitted.

They set off for Haines Mission on the coast, following a trail blazed through the mountains by Jack Dalton, an earlier pioneer. In good weather this was a four-day trip; at −25 degrees Fahrenheit it took them twenty-nine days. The horses gave up and had to be shot. Some humans also succumbed and were prepared to die on the spot, but Boyle would have none of that. In the words of one of his biographers, “he drove them like a chain gang,” alternately making promises, cajoling, and insulting them as he spurred them on. They staggered into Haines on November 23 and managed to pick up a ship to Seattle. There, Boyle was presented with a gold watch by his followers who swore that without his leadership no one would have reached the coast alive.

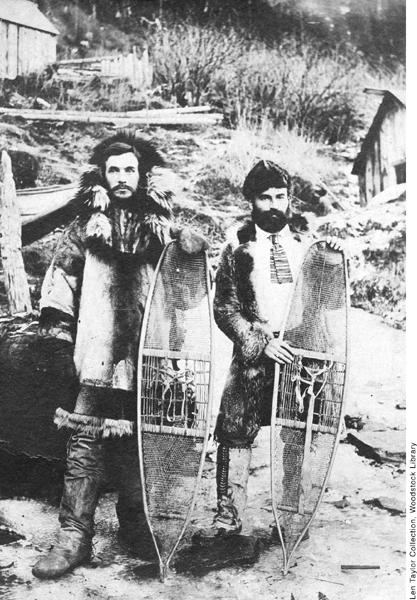

Joe Boyle and the eccentric Swiftwater Bill Gates (in dress shirt and four-in-hand tie) on their way to the Outside in the autumn of 1897 while the rush was still on

.

It had soon become obvious to Boyle that the day of the individual placer miner was over. The thousands who rushed to the Klondike talked in terms of “digging for gold” as if the ground was knee-deep in nuggets. To their dismay, they were faced with a back-breaking procedure. Seeking out the hidden paystreak by thawing the ground with fire or steam and then drilling a shaft to bedrock was always a gamble. You might drill half a dozen shafts yet miss the serpentine paystreak, and even if you found the line of the old stream bed, it could turn out to be barren of gold. Those who did not give up and who were lucky enough to come upon the elusive evidence of a prehistoric watercourse then had the tedious task of hauling up the pay dirt, bucket by bucket, and sluicing it free of its treasure. Only about 25 percent of the available gold was recovered by this procedure.

Boyle was convinced that in order to separate the gold from the bedrock the leafy valleys would have to be torn apart, ripped up by huge nozzles. The gold would then be dug up by electrically powered dredges floating on ponds of their own creation, biting into the bedrock with an endless line of moving buckets and washing the gold free in monstrous revolving sieves.

The principle was not new; small gold dredges had operated well before Boyle devised his plan, but there was a difference. Boyle proposed to build huge dredges and to haul the necessary machinery—tons and tons of it—up the White Pass trail, over the mountains, down the fast-flowing Yukon to Dawson, and out by gravel road to the gold creeks—all in the shortest possible time.

The details would have daunted a lesser man. The entire dredge system would run on electricity, which meant building a hydroelectric power plant, digging vast ditches, and using the water of the north fork of the Klondike River to achieve his ends. And all this in a land when the first snow fell early in October and the country stayed frozen until April.

Speed was essential. Swiftwater Bill was off to San Francisco’s Baldwin Hotel, where he tipped bellboys with gold dust to page him by name and continued to woo not only Gussie Lamore, who it developed was already married, but also her two sisters, Nellie and Grace. Joe Boyle headed for Ottawa.

In the capital while waiting for Parliament to sit, he encountered the diminutive Englishman who would become his rival in the Klondike. This was Arthur Christian Newton Treadgold, a direct descendant of Sir Isaac Newton, the renowned scientist. Himself an Oxford graduate and teacher, he was for the moment correspondent for the

Mining Journal

and the

Manchester Guardian

. That wasn’t much more than a cover. Treadgold had ideas as big as Boyle’s about controlling the Klondike goldfields. But Treadgold was wary of dredges. He thought instead of using giant scrapers and land-going digging machines, none of which ever worked.

This odd pair, around whose personalities so much of the Klondike’s mining history revolves, were opposites in every way. Treadgold was short and stubby with a shaggy blond moustache and a face that was all teeth when he smiled, in contrast to the robust former boxer. Treadgold was conceited, secretive, and cunning, quite prepared to flirt with the truth if it suited his purposes, an incompetent manager, possessed of an uncontrollable temper and an inability to take advice—character flaws that would eventually doom him. Boyle, on the other hand, was a big man in every way, open-minded and open-hearted, who scorned personal publicity but could be a terrier when facing setbacks to his personal plans for corralling the Klondike gold. It was significant that Treadgold to his employees and friends was always “Mr. Treadgold.” Boyle to all and sundry was simply “Joe.”

Both men had one quality in common: they were adept at raising funds for their ventures. Each had the ability to charm financiers with deep pockets. There was a certain magic in the word Klondike that conjured up visions of unlimited profits. It did not seem to occur to normally hard-headed investors that the Klondike’s main resource was a diminishing one. Gold was not grain. Two of the richest families in America—the Guggenheims and the Rothschilds—were included in dredging enterprises after the turn of the century, ventures that included both Boyle and Treadgold, each of whom was prepared, it seemed, to sell his soul in order to gain control of the Klondike’s resources.

In Ottawa Boyle pressed his case for a hydraulic lease on Clifford Sifton, Wilfrid Laurier’s Minister of the Interior. In June 1898 he got part of what he wanted: an undertaking in writing reserving eight miles of the Klondike Valley, rim to rim, exclusively for hydraulic operations. In November 1900 the government issued a lease in his favour. This was the famous Boyle Concession, which effectively barred all individual prospecting in the area and caused so much controversy in the Yukon. Boyle clung to it through a series of lawsuits and counter-suits that would have dampened the ardour of a less persistent man. His daughter Flora has testified to the passion with which he flung himself into each new legal battle. “Lawsuit,” she wrote, “was his middle name.” He loved a fight. Each time he was sued he immediately countersued. Before he achieved his aim he had lawyers in Dawson City, Vancouver, London, New York, and Detroit.

To describe his reputation in Dawson during the early days as controversial would be an understatement. Meetings were held, petitions forwarded to Ottawa, and local politicians pressured in a series of attempts to cancel the Boyle Concession. The timber rights to that chunk of the Klondike Valley were as valuable as the ground that lay beneath. Because lumber was needed for sluice boxes and cabins on the creeks, Dawson was enjoying a building boom that saw the price of logs soar from $18 a cord in December 1898 to $48 a cord the following summer. Boyle saw this coming. He and Slavin (who later left the partnership) established a sawmill near the mouth of the Klondike River that turned out more than a million feet of dressed lumber in 1899. Much of the timber came from his own property, an asset so valuable that it is said he was forced to drive poachers off at rifle point.

Meanwhile, in New York City, Treadgold sweet-talked Daniel Guggenheim into a major investment to buy up as many claims as possible in the heart of the gold country in order to consolidate water and mineral rights on the richest creeks—Hunker, Bonanza, and Eldorado. By the summer of 1901, he too had wheedled a hydraulic concession out of Ottawa, one that was arranged to free him from any of the work commitments prescribed by mining law, thus tying up the gold country for six years. It was, in the heated words of the

Klondike Nugget

, “a malignant and unpardonable outrage … the blackest act of infamy that ever blotted the history of the country.” After a storm of protest the government cancelled the Treadgold hydraulic concession. Boyle went on to form the Canadian Klondyke Company with backing from the Rothschild interests in Detroit; Treadgold would shortly become resident director of the rival Yukon Gold Corporation, a Guggenheim enterprise.

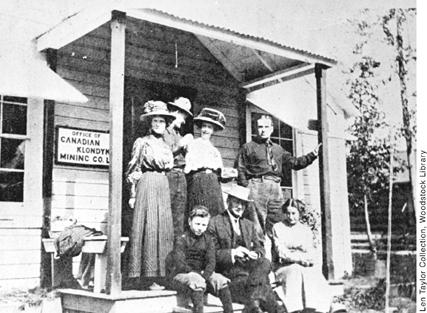

Joe Boyle (back row, right) at the Bear Creek office of his Canadian Klondyke Mining Company in the heart of the gold country

.

When I was a small boy in Dawson the name Treadgold seemed to pop up in every conversation around our dinner table. Boyle was gone by then, but Treadgold was very much alive, the central figure in a tangle of court actions that occupied him for most of his days. He left the Guggenheims, formed his own mining company, and had his eye on the Boyle interests, hoping to consolidate all corporate mining into one big enterprise. He failed, went broke, and left the Klondike, apparently forever, only to return in the mid-twenties after Boyle’s death to pursue his dream. Even then “Klondike” had a touch of magic for investors, and Treadgold, with his smooth tongue and a name that hinted at riches underfoot, was able to form the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation out of borrowed money and the remnants of earlier ventures. (I worked for it in the late thirties as a young mucker.) In the end Treadgold was eased out and lost everything. But in 1951, when he died at the age of eighty-seven, several of the original Boyle dredges were still churning up the pay dirt in the golden valleys of the Klondike.

—TWO—

Boyle spent almost two decades of his adult life in the Yukon. He liked to claim that he had arrived in Dawson with only nineteen dollars in his pocket. In his pocket, no doubt, but in the bank? In New York he had operated a lucrative feed and grain business, and though he was clearly hard-pressed for money—he depended on boxing exhibitions for his living after his New York stay—it stretches the imagination to suggest he was penniless. Clearly he was not without resources. It cost money to travel to Ottawa, and it cost more to live at the Russell House, the most luxurious hotel in the capital. Boyle certainly put whatever money he had to good use, as William Rodney has noted. He owned among other things several valuable pieces of Dawson real estate, a 20-foot-long wharf, a warehouse 100 feet long, a lumber dock, a half interest in a hydraulic grant, and 16 placer claims. His sawmill was certainly profitable, though Boyle and Slavin would have needed some sort of nest egg to launch it. But ten years after he arrived he would be a millionaire—self-made and proud of it, as his casual reference to the nineteen dollars suggests.