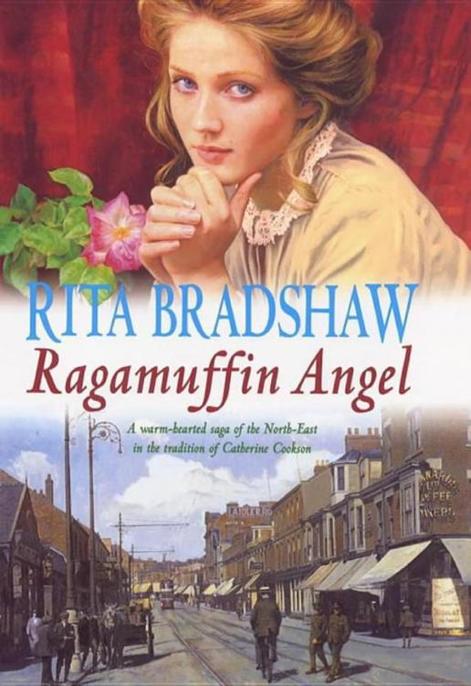

Ragamuffin Angel

Ragamuffin Angel

RITA BRADSHAW

headline

Copyright © 2000 Rita Bradshaw

The right of Rita Bradshaw to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2010

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This Ebook produced by Jouve Digitalisation des Informations

eISBN : 978 0 7553 7585 1

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Table of Contents

Rita Bradshaw was born in Northampton, where she still lives today with her husband (whom she met when she was sixteen) and their family.

When she was approaching forty she decided to fulfil two long-cherished ambitions – to write a novel and learn to drive. She says, ‘the former was pure joy and the latter pure misery,’ but the novel was accepted for publication and she passed her driving test. She has gone on to write many successful novels under a pseudonym.

As a committed Christian and fervent animal lover, Rita has a full and busy life, but she relishes her writing – a job that is all pleasure – and loves to read, walk her dogs, eat out and visit the cinema in any precious spare moments.

In memory of Hannah Eley, a very special little girl who had the face of an angel and a spirit to match Connie’s any day! In spite of all the pain borne so bravely in her eleven years on this earth, she was sunshine and laughter and everything that is good in the world, and we all miss her more than words can say.

Part One

1900

The House In The Wood

Chapter One

The January night was raw and cold, the sort of mind-numbing cold that only the biting winters of the north produce, and the thin splinters of ice in the driving wind caused the man emerging from the dark cobbled street to tuck his muffler more securely into the neck of his thick cloth coat.

He glanced back the way he had come as he paused, pulling his cap further down on to his forehead, but there were no running footsteps, shrieks or cries disturbing the frozen streets, in spite of the scene he had just endured. And he knew who had been behind that, by, he did. He’d known immediately he’d stepped through the front door that her mam had been round to see her the day.

He began to walk swiftly now and with intent, not, as one might have expected, past Mowbray Park and towards the hub of the town centre of the rapidly growing Bishopwearmouth, where the countless pubs and working men’s clubs provided a brief haven from the daily grind for hundreds of Sunderland’s working men. He turned in the opposite direction, entering Mowbray Road, towards Tunstall Vale, and when he was hailed by two other men as they emerged from a side road he merely raised an abrupt hand in response, his walk checked in no way.

‘By, Jacob’s in a tear the night.’

It was said laughingly, even mockingly, and the second man answered in the same tone, shaking his head the while. ‘It’s fair amazin’ what some women’ll put up with. Now, my Bertha’d break me legs afore she’d consent to what his missus allows.’

‘Aye, well likely Jacob’s lass don’t have too much say in the matter, eh?’

‘Aye, man, you could be right there. Damn shame though, I call it. They’ve not bin wed six year an’ she’s a bonny lass when all’s said an’ done. Aye, it’s a shame right enough.’

The men didn’t elaborate on what was a shame, but now there was no laughter softening the rough Sunderland idiom as the two of them stared after the big figure, which had long since been swallowed by the freezing darkness.

‘Makes you wonder though, don’t it, what goes on behind locked doors? Aye, it makes you wonder . . .’

The lone form of Jacob Owen was walking even faster now, in spite of the glassy pavements and the banks of frozen snow either side of the footpath, and before long he had left the last of the houses bordering Tunstall Road far behind, passing Strawberry Cottage and then, a few hundred yards further on, Red House. The sky was low and laden with the next load of snow, and with no lights piercing the thick blackness the darkness was complete, but it would have been obvious even to a blind man that Jacob had trod the path many times before as he strode swiftly on, his head down and his shoulders hunched against the bitter wind.

Just past Tunstall Hills Farm Jacob turned off the road, climbing over a dry stone wall and into the fields beyond, where the mud and grass were frozen hard. The going was more difficult now; the ridges of mud interspersed with snow and puddles of black ice were treacherous, and the blizzard forecast earlier that day was sending its first whirling flakes into the wind, obliterating even the faintest glow from the moon, but Jacob’s advance was faster if anything.

When he turned into a thickly wooded area some minutes later, he emerged almost immediately into a large clearing in which a tiny ramshackle thatched cottage stood, a small lean-to attached to the side of it enclosing a large supply of neatly sawn logs piled high against the wall of the dwelling place.

Now, for the first time since leaving the sprawling outskirts of the town of Bishopwearmouth, Jacob stopped dead, drawing in a deep hard breath as he ran his hand over his face, which in spite of the rawness of the night was warm with sweat. His eyes took in the thin spiral of smoke coming from the cottage chimney, and, as though it was a welcome in itself, he smiled and exhaled.

He was across the clearing and its freshly dug vegetable patch in a few strides, the thickly falling snow just beginning to patch the spiky winter grass at the edge of the plot of land with ethereal beauty, and he opened the cottage door without knocking or waiting.

For a moment he stood outlined in the glow and warmth of the cosily lit room beyond, and then the sound of voices drew the dark silhouette inwards, the door was shut and all was quiet again.

It was some two hours later that the lone hoot of an owl was disturbed by a band of men-five in all-moving stealthily into the clearing from the exact spot Jacob had emerged from earlier. The snow was now a thick blanket muffling any sound they might have made, and the whirling curtain of white provided extra cover as they approached the cottage, their big hobnailed boots marking the virgin purity with deep indentations.

The first man, who was small and stocky, paused at the side of the curtained window, gathering the others around him in the manner of a general marshalling his troops. ‘We’re all agreed with what needs to be done then?’

‘I don’t like this, John.’

‘For crying out loud, Art!’ The first man rounded on the much taller man who had spoken, his voice a low hiss. ‘He’s making our name a byword and you know it. Mam said Mavis was beside herself again this morning when she called in. You know what folk are saying as well as me; why, when Mavis Owen has got five brothers, does her man think he can get away with keeping a fancy woman in the house in the wood? And they’re right, damn it. We should have stepped in months ago when Mam first found out what was what.’

‘I know Mam would have it that’s what people are saying. I’m not so sure myself.’

‘Don’t talk daft, man.’

‘Aye, well supposing you’re right, how does tonight solve anything? If Sadie Bell has already given him one bairn he’s not likely to walk away just because we tell him to, now is he? And there’s talk she’s expecting another.’

‘I don’t care how many bastards his whore drops, he’ll do what we tell him and finish it. And who says this third one is Jacob’s anyway? Her stomach was already full when she came snivelling back from Newcastle years ago, so that’s two bastards to two different men as we know of. She’s likely got blokes visiting here every night of the week.’ The smaller man’s tone was pugnacious, his voice a low growl.

‘I don’t think she’s like that.’

‘I’ve heard it all now.’ The smaller man turned his head as though in appeal to the other three, who all shifted uncomfortably. ‘She’s a trollop, the sort who’d open her legs for anyone, and what really sticks in my craw is that she hooked Jacob when she was working at the firm. You think she doesn’t laugh up her sleeve at us all? Oh aye, I know her sort all right.’

He didn’t doubt it. Art Stewart looked at his oldest brother – whom he had never liked – and he had a job to keep his thoughts to himself. He had shared a bedroom with this brother once the twins, Gilbert and Matthew, who were four years younger than him, had been weaned, and he knew John had had women from puberty onwards and that he had paid for them most of the time.

‘What are you going to say to him, John?’

This last was spoken by Dan who, at fourteen, was the baby of the Stewart family, but although his face had the look of a young boy, his physique was already that of a man, and he towered over his oldest brother by a good three or four inches. He was a good-looking lad – all the Stewart boys were, and their sister, Mavis, who at twenty-five was the second born, was also far from plain – and like Art and the twins he was tall and lean; it had been left to the eldest two, John and Mavis, to inherit their mother’s small, chunky stature.

‘I’ll tell him all this is finished.’ John’s hand made a wide sweeping motion towards the cottage.

‘And . . . and if Art’s right and Jacob won’t listen?’

John brushed the snow from his shoulders, taking off his cap and shaking it before pulling it back over his thick springy hair, his actions slow and deliberate. It was a full thirty seconds before he responded to the question, and then his voice carried a grating sound when he said, ‘Then we’ll have to make him listen, lad, won’t we. We’re here tonight so’s his whore can see we mean business and her meal ticket’s finished, all right? Mam said it’s the only way and she’s right. Gilbert, Matt, you with me on this?’

Other books

Committed (Book 2) (30 Days) by Larsen, K

Redeeming Kyle: 69 Bottles #3 by Zoey Derrick

A Mind of Winter by Shira Nayman

Mourning Becomes Cassandra by Christina Dudley

Zombie Town by Stine, R.L.

Through Glass: Episode Four by Rebecca Ethington

Trying the Knot by Todd Erickson

The Heartbreakers by Ali Novak

Call Me Grim by Elizabeth Holloway