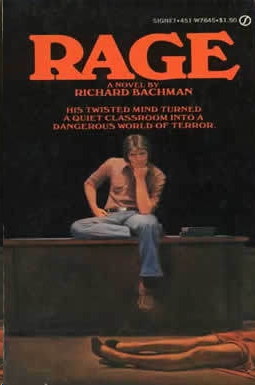

Rage

Stephen King

Richard Bachman

RAGE

Publisher: New English Library Ltd

(February 1, 1983)

ISBN-10: 0450053792

ISBN-13: 978-0450053795

A high school Show-and-Tell session explodes into a nightmare of evil

So you understand that when we increase the number of variables, the axioms themselves never change.

- Mrs. Jean Underwood

Teacher, teacher, ring the bell, My lessons all to you I'll tell, And when my day at school is through, I'll know more than aught I knew.

- Children's rhyme, c. 1880

Chapter 1

The morning I got it on was nice; a nice May morning. What made it nice was that I'd kept my breakfast down, and the squirrel I spotted in Algebra II.

I sat in the row farthest from the door, which is next to the windows, and I spotted the squirrel on the lawn. The lawn of Placerville High School is a very good one. It does not fuck around. It comes right up to the building and says howdy. No one, at least in my four years at PHS, has tried to push it away from the building with a bunch of flowerbeds or baby pine trees or any of that happy horseshit. It comes right up to the concrete foundation, and there it grows, like it or not. It is true that two years ago at a town meeting some bag proposed that the town build a pavilion in front of the school, complete with a memorial to honor the guys who went to Placerville High and then got bumped off in one war or another. My friend Joe McKennedy was there, and he said they gave her nothing but a hard way to go. I wish I had been there. The way Joe told it, it sounded like a real good time. Two years ago. To the best of my recollection, that was about the time I started to lose my mind.

Chapter 2

So there was the squirrel, running through the grass at 9:05 in the morning, not ten feet from where I was listening to Mrs. Underwood taking us back to the basics of algebra in the wake of a horrible exam that apparently no one had passed except me and Ted Jones. I was keeping an eye on him, I can tell you. The squirrel, not Ted.

On the board, Mrs. Underwood wrote this: a = 16. "Miss Cross," she said, turning back. "Tell us what that equation means, if you please."

"It means that a is sixteen," Sandra said. Meanwhile the squirrel ran back and forth in the grass, tail bushed out, black eyes shining bright as buckshot. A nice fat one. Mr. Squirrel had been keeping down more breakfasts than I lately, but this morning's was riding as light and easy as you please. I had no shakes, no acid stomach. I was riding cool.

"All right," Mrs. Underwood said. "Not bad. But it's not the end, is it? No. Would anyone care to elaborate on this fascinating equation?"

I raised my hand, but she called on Billy Sawyer. "Eight plus eight," he blurted.

"Explain. "

"I mean it can be

" Billy fidgeted. He ran his fingers over the graffiti etched into the surface of his desk; SM L DK, HOT SHIT, TOMMY '73. "See, if you add eight and eight, it means

"

"Shall I lend you my thesaurus?" Mrs. Underwood asked, smiling alertly. My stomach began to hurt a little, my breakfast started to move around a little, so I looked back at the squirrel for a while. Mrs. Underwood's smile reminded me of the shark in Jaws.

Carol Granger raised her hand. Mrs. Underwood nodded. "Doesn't he mean that eight plus eight also fulfills the equation's need for truth?"

"I don't know what he means," Mrs. Underwood said.

A general laugh. "Can you fulfill the equation's truth in any other ways, Miss Granger?"

Carol began, and that was when the intercom said: "Charles Decker to the office, please. Charles Decker. Thank you."

I looked at Mrs. Underwood, and she nodded. My stomach had begun to feel shriveled and old. I got up and left the room. When I left, the squirrel was still scampering.

I was halfway down the hall when I thought I heard Mrs. Underwood coming after me, her hands raised into twisted claws, smiling her big shark smile. We don't need boys of your type around here

boys of your type belong in Greenmantle

or the reformatory

or the state hospital for the criminally insane

so get out! Get out! Get out!

I turned around, groping in my back pocket for the pipe wrench that was no longer there, and now my breakfast was a hard hot ball inside my guts. But I wasn't afraid, not even when she wasn't there. I've read too many books.

Chapter 3

I stopped in the bathroom to take a whiz and eat some Ritz crackers. I always carry some Ritz crackers in a Baggie. When your stomach's bad, a few crackers can do wonders. One hundred thousand pregnant women can't be wrong. I was thinking about Sandra Cross, whose response in class a few minutes ago had been not bad, but also not the end. I was thinking about how she lost her buttons. She was always losing them-off blouses, off skirts, and the one time I had taken her to a school dance, she had lost the button off the top of her Wranglers and they had almost fallen down. Before she figured out what was happening, the zipper on the front of her jeans had come halfway unzipped, showing a V of flat white panties that was blackly exciting. Those panties were tight, white, and spotless. They were immaculate. They lay against her lower belly with sweet snugness and made little ripples while she moved her body to the beat

until she realized what was going on and dashed for the girls' room. Leaving me with a memory of the Perfect Pair of Panties. Sandra was a Nice Girl, and if I had never known it before, I sure-God knew it then, because we all know that the Nice Girls wear the white panties. None of that New York shit is going down in Placerville, Maine.

But Mr. Denver kept creeping in, pushing away Sandra and her pristine panties. You can't stop your mind; the damn thing just keeps right on going. All the same, I felt a great deal of sympathy for Sandy, even though she was never going to figure out just what the quadratic equation was all about. If Mr. Denver and Mr. Grace decided to send me to Greenmantle, I might never see Sandy again. And that would be too bad.

I got up from the hopper, dusted the cracker crumbs down into the bowl, and flushed it. High-school toilets are all the same; they sound like 747s taking off. I've always hated pushing that handle. It makes you sure that the sound is clearly audible in the adjacent classroom and that everybody is thinking: Well, there goes another load. I've always thought a man should be alone with what my mother insisted I call lemonade and chocolate when I was a little kid. The bathroom should be a confessional sort of place. But they foil you. They always foil you. You can't even blow your nose and keep it a secret. Someone's always got to know, someone's always got to peek. People like Mr. Denver and Mr. Grace even get paid for it.

But by then the bathroom door was wheezing shut behind me and I was in the hall again. I paused, looking around. The only sound was the sleepy hive drone that means it's Wednesday again, Wednesday morning, ten past nine, everyone caught for another day in the splendid sticky web of Mother Education.

I went back into the bathroom and took out my Flair. I was going to write something witty on the wall like SANDRA CROSS WEARS WHITE UNDERPANTS, and then I caught sight of my face in the mirror. There were bruised half-moons under my eyes, which looked wide and white and stary. The nostrils were half-flared and ugly. The mouth was a white, twisted line.

I Wrote EAT SHIT On the wall until the pen suddenly snapped in my straining fingers. It dropped on the floor and I kicked it.

There was a sound behind me. I didn't turn around. I closed my eyes and breathed slowly and deeply until I had myself under control. Then I went upstairs.

Chapter 4

The administration offices of Placerville High are on the third floor, along with the study hall, the library, and Room 300, which is the typing room. When you push through the door from the stairs, the first thing you hear is that steady clickety-clack. The only time it lets up is when the bell changes the classes or when Mrs. Green has something to say. I guess she usually doesn't say much, because the typewriters hardly ever stop. There are thirty of them in there, a battle-scarred platoon of gray Underwoods. They have them marked with numbers so you know which one is yours. The sound never stops, clickety-clack, clickety-clack, from September to June. I'll always associate that sound with waiting in the outer office of the admin offices for Mr. Denver or Mr. Grace, the original dipso-duo. It got to be a lot like those jungle movies where the hero and his safari are pushing deep into darkest Africa, and the hero says: "Why don't they stop those blasted drums?" And when the blasted drums stop he regards the shadowy, rustling foliage and says: "I don't like it. It's too quiet."

I had gotten to the office late just so Mr. Denver would be ready to see me, but the receptionist, Miss Marble, only smiled and said, "Sit down, Charlie. Mr. Denver will be right with you. "

So I sat down outside the slatted railing, folded my hands, and waited for Mr. Denver to be right with me. And who should be in the other chair but one of my father's good friends, AI Lathrop. He was giving me the old slick-eye, too, I can tell you. He had a briefcase on his lap and a bunch of sample textbooks beside him. I had never seen him in a suit before. He and my father were a couple of mighty hunters. Slayers of the fearsome sharp-toothed deer and the killer partridge. I had been on a hunting trip once with my father and Al and a couple of my father's other friends. Part of Dad's never-ending campaign to Make a Man Out of My Son.

"Hi, there!" I said, and gave him a big shiteating grin. And I could tell from the way he jumped that he knew all about me.

"Uh, hi, uh, Charlie. " He glanced quickly at Miss Marble, but she was going over attendance lists with Mrs. Venson from next door. No help there. He was all alone with Carl Decker's psychotic son, the fellow who had nearly killed the chemistry-physics teacher.

"Sales trip, huh?" I asked him.

"Yeah, that's right. " He grinned as best he could. "Just out there selling the old books."

"Really crushing the competition, huh?"

He jumped again. "Well, you win some, you lose some, you know, Charlie."

Yeah, I knew that. All at once I didn't want to put the needle in him anymore. He was forty and getting bald and there were crocodile purses under his eyes. He went from school to school in a Buick station wagon loaded with textbooks and he went hunting for a week in November every year with my father and my father's friends, up in the Allagash. And one year I had gone with them. I had been nine, and I woke up and they had been drunk and they had scared me. That was all. But this man was no ogre. He was just forty-baldish and trying to make a buck. And if I had heard him saying he would murder his wife, that was just talk. After all, I was the one with blood on my hands.

But I didn't like the way his eyes were darting around, and for a moment just a moment-I could have grabbed his windpipe between my hands and yanked his face up to mine and screamed into it: You and my father and all your friends, you should all have to go in there with me, you should all have to go to Greenmantle with me, because you're all in it, you're all in it, you're all a part of this!

Instead I sat and watched him sweat and thought about old times.

Chapter 5

I came awake with a jerk out of a nightmare I hadn't had for a long time; a dream where I was in some dark blind alley and something was coming for me, some dark hunched monster that creaked and dragged itself along

a monster that would drive me insane if I saw it. Bad dream. I hadn't had it since I was a little kid, and I was a big kid now. Nine years old.

At first I didn't know where I was, except it sure wasn't my bedroom at home. It seemed too close, and it smelled different. I was cold and cramped, and I had to take a whiz something awful.

There was a harsh burst of laughter that made me jerk in my bed-except it wasn't a bed, it was a bag.

"So she's some kind of fucking bag," Al Lathrop said from beyond the canvas wall, "but fucking's the operant word there."

Camping, I was camping with my dad and his friends. I hadn't wanted to come.

"Yeah, but how do you git it up, Al? That's what I want to know. " That was Scotty Norwiss, another one of Dad's friends. His voice was slurred and furry, and I started to feel afraid again. They were drunk.

"I just turn off the lights and pretend I'm with Carl Decker's wife," Al said, and there was another bellow of laughter that made me cringe and jerk in my sleeping bag. Oh, God, I needed to whiz piss make lemonade whatever you wanted to call it. But I didn't want to go out there while they were drinking and talking.

I turned to the tent wall and discovered I could see them. They were between the tent and the campfire, and their shadows, tall and alien-looking, were cast on the canvas. It was like watching a magic lantern show. I watched the shadow-bottle go from one shadow-hand to the next.

"You know what I'd do if I caught you with my wife?" My dad asked Al.

"Probably ask if I needed any help," Al said, and there was another burst of laughter. The elongated shadow-heads on the tent wall bobbed up and down, back and forth, with insectile glee. They didn't look like people at all. They looked like a bunch of talking praying mantises, and I was afraid.

"No, seriously," my dad said. "Seriously. You know what I'd do if I caught somebody with my wife?"

"What, Carl?" That was Randy Earl.

"You see this?"

A new shadow on the canvas. My father's hunting knife, the one he carried out in the woods, the one I later saw him gut a deer with, slamming it into the deer's guts to the hilt and then ripping upward, the muscles in his forearm bulging, spilling out green and steaming intestines onto a carpet of needles and moss. The firelight and the angle of the canvas turned the hunting knife into a spear.

"You see this son of a bitch? I catch some guy with my wife, I'd whip him over on his back and cut off his accessories."

"He'd pee sitting down to the end of his days, right, Carl?" That was Hubie Levesque, the guide. I pulled my knees up to my chest and hugged them. I've never had to go to the bathroom so bad in my life, before or since.

"You're goddamn right," Carl Decker, my sterling Dad, said.

"Wha' about the woman in the case, Carl?" Al Lathrop asked. He was very drunk. I could even tell which shadow was his. He was rocking back and forth as if he was sitting in a rowboat instead of on a log by the campfire. "Thass what I wanna know. What do you do about a woman who less-lets-someone in the back door? Huh?"

The hunting knife that had turned into a spear moved slowly back and forth. My father said, "The Cherokees used to slit their noses. The idea was to put a cunt right up on their faces so everyone in the tribe could see what part of them got them in trouble."

My hands left my knees and slipped down to my crotch. I cupped my testicles and looked at the shadow of my father's hunting knife moving slowly back and forth. There were terrible cramps in my belly. I was going to whiz in my sleeping bag if I didn't hurry up and go.

"Slit their noses, huh?" Randy said. "That's pretty goddamn good. If they still did that, half the women in Placerville would have a snatch at both ends. "

"Not my wife," my father said very quietly, and now the slur in his voice was gone, and the laughter at Randy's joke stopped in mid-roar.

"No, 'course not, Carl," Randy said uncomfortably. "Hey, shit. Have a drink. "

My father's shadow tipped the bottle back.

"I wun't slit her nose," A1 Lathrop said. "I'd blow her goddamn cheatin' head off. "

"There you go," Hubie said. "I'll drink to it."

I couldn't hold it anymore. I squirmed out of the sleeping bag and felt the cold October air bite into my body, which was naked except for a pair of shorts. It seemed like my cock wanted to shrivel right back into my body. And the one thing that kept going around and around in my mind-I was still partly asleep, I guess, and the whole conversation had seemed like a dream, maybe a continuation of the creaking monster in the alley-was that when I was smaller, I used to get into my mom's bed after Dad had put on his uniform and gone off to work in Portland, I used to sleep beside her for an hour before breakfast.

Dark, fear, firelight, shadows like praying mantises. I didn't want to be out in these woods seventy miles from the nearest town with these drunk men. I wanted my mother.

I came out through the tent flap, and my father turned toward me. The hunting knife was still in his hand. He looked at me, and I looked at him. I've never forgotten that my dad with a reddish beard stubble on his face and a hunting cap cocked on his head and that hunting knife in his hand. All the conversation stopped. Maybe they were wondering how much I had heard. Maybe they were even ashamed.

"What the hell do you want?" my dad asked, sheathing the knife.

"Give him a drink, Carl," Randy said, and there was a roar of laughter. Al laughed so hard he fell over. He was pretty drunk.

"I gotta whiz," I said.

"Then go do it, for Christ's sake," my dad said.

I went over in the grove and tried to whiz. For a long time it wouldn't come out. It was like a hot soft ball of lead in my lower belly. I had nothing but a fingernail's length of penis-the cold had really shriveled it. At last it did come, in a great steaming flood, and when it was all out of me, I went back into the tent and got in my sleeping bag. None of them looked at me. They were talking about the war. They had all been in the war.

My dad got his deer three days later, on the last day of the trip. I was with him. He got it perfectly, in the bunch of muscle between neck and shoulder, and the buck went down in a heap, all grace gone.

We went over to it. My father was smiling, happy. He had unsheathed his knife. I knew what was going to happen, and I knew I was going to be sick, and I couldn't help any of it. He planted a foot on either side of the buck and pulled one of its legs back and shoved the knife in. One quick upward rip, and its guts spilled out on the forest floor, and I turned around and heaved up my breakfast.

When I turned back to him, he was looking at me. He never said anything, but I could read the contempt and disappointment in his eyes. I had seen it there often enough. I didn't say anything either. But if I had been able to, I would have said: It isn't what you think.

That was the first and last time I ever went hunting with my dad.