Rasputin (5 page)

Authors: Frances Welch

There was the odd scandal, including a woman who claimed he had raped her in his cellar. But the doughty Praskovia took it all in her stride. Indeed, she convinced herself that sex was a burden for her Grishka. She was learning well: altruistic sin was one of her husband's favourite notions. He maintained that he generously took upon himself the sin of each of his sexual encounters and, further, that these sins reduced the overall amount in the world. Presumably he nodded his whiskery head

sagely as Praskovia lamented: âEach man must bear his cross and this is his.'

After more pressure from the irascible Father Peter, an inquiry into Rasputin's activities was launched in Pokrovskoye in 1903 by Bishop Anthony of Tobolsk. Rasputin never had any official role within the Church, but some of the Church leaders clearly felt that his spiritual activities fell under their jurisdiction. A policeman snuck into his services dressed as a peasant. Unfortunately for Father Peter, the inquiry foundered, as the policeman not only failed to find anything irregular, but succumbed to a full-blown attack of what would become known as â

Rasputinschina

'.

R

asputin was aged 33 when he decided he had had enough of rustic life and set out on a near-600-mile walk to the nearest city, Kazan. Or at least that is how it would appear. It is hard to tell how purposeful Rasputin actually was in many of the things he did in his life â to what extent he directed himself and to what extent his actions were dictated by random moods and circumstances.

It was in Kazan that he had his first taste of fine living, sitting in lavishly carpeted rooms, watching gentlefolk sip tea rather than suck it through sugar. His subsequent passion for gadgets was inspired by this first sight of radios, electric lights and, most importantly, telephones.

The telephone was to become a staple of Rasputin's life. In later years he would use the phone to vet women callers, asking how old they were and what they looked like, before making appointments. He and his daughter Maria became notorious for making nuisance calls. Maria would make suggestive overtures to men listed in the phone directory, while Rasputin enjoyed exposing bashful supporters when he knew they had company, waiting on the line with grim satisfaction, as the manservant delivered the unwelcome news: âI have Grishka Rasputin on the phone.' His happiest moments on the telephone, however, were spent dancing: a singer friend would run through a medley of songs while he clutched the receiver and danced in squats, twirls and stamps.

Shortly after his arrival in Kazan, Rasputin managed to gain the confidence of one particular cleric after warning him of a knife attack. But other clerics were not so impressed by his burgeoning love of the

bath-house

. They heard that he was inviting women to wash his genitals: âTake off your clothes and wash the

muzhik

' [peasant]. The women would watch as he, at least in theory, controlled himself; they would then thrash him with twigs. At one point he took two sisters, aged 15 and 20, for a thorough session of washing and thrashing. When he was accosted by their outraged mother, he pronounced grandly: âNow you may feel at peace. The Day of Salvation has dawned for your daughters.' An accusation levelled at Rasputin by the Tobolsk Theological Consistory concerning his âodd behaviour towards women' did nothing to dampen his ardour. Indeed, the joys of urban life took such a hold that he was soon gravitating from Kazan towards the larger city of Kiev.

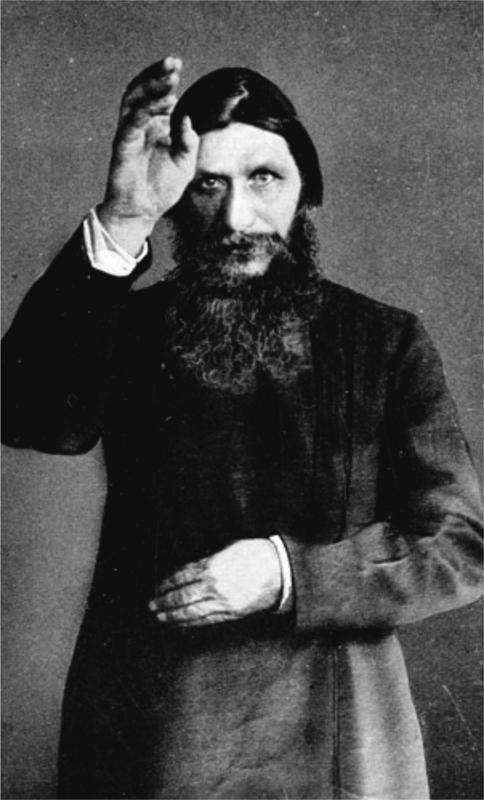

It was widely acknowledged that the Man of God's eyes were mesmeric and that he could expand and contract the pupils at will

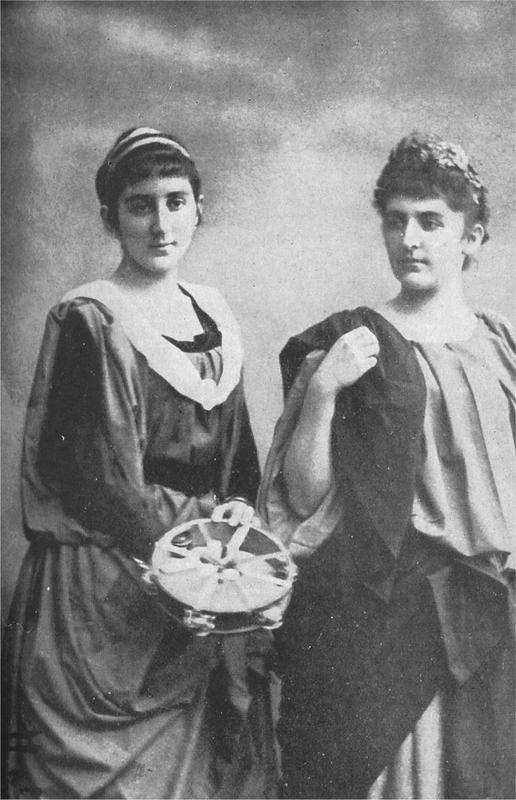

In Kiev he had his first encounter with Russia's Imperial family. Grand Duchess Militza was married to the Tsar's cousin, Grand Duke Peter, and was the elder of two Montenegrin princesses, known as the âBlack Sisters' or âBlack Peril'. She considered herself a religious expert and in the early 1900s was the proud author of âSelected Passages from the Holy Fathers'.

Intrigued by tales of Rasputin's powers, Militza, then visiting Kiev, tracked him down to an obscure shed, where she found him sawing wood. She and her younger sister, Princess Anastasia, had once been considered great beauties at Court. Militza retained a soulful face, with large, dark, sorrowful eyes and a delicate mouth, but by this time she was well into her thirties and evidently held no interest for Rasputin. Though aware of her presence, he carried on sawing noisily. She told him to sit down but he refused; when she asked how long he would remain in Kiev, he replied curtly that God would tell him when he should leave. His abrasiveness and her conciliatory responses would become characteristic of Rasputin's exchanges with members of the aristocracy, who were prone to welcome his rudeness as a mark of integrity.

Their second meeting was altogether happier. Rasputin had arrived in the Russian capital, St Petersburg, in 1903. His unlikely claim was that he had come to raise money for the church at Pokrovskoye. Whatever was behind his motivations, he seems to have decided, at this point, that it might be worth being civil to grand duchesses after all. He paid a visit to Militza and her younger âblack sister', Anastasia. Completing a formidable party would be the Tsar's so-called âdread uncle', Grand Duke Nicholas.

The Montenegrin Princesses Anastasia and Militza, with a tambourine, circa 1890. The Black Peril, as they became known, were considered great beauties.

Â

It emerged, during the visit, that Anastasia was consumed with worry about her dog: vets had given him barely two months to live and he was breathing heavily. Tea was postponed while Rasputin put his hand on the dog's head, shut his eyes and prayed for a good half-hour. When the dog's breathing improved, the Grand Duke stepped forward jubilantly, but was brazenly waved away. By the end of the prayer, the dog was restored to health and keen to lick his healer's well-seasoned hand. Rasputin issued a bald pronouncement, which would, in fact, prove accurate: âHe will live for some years.'

Years later, when Rasputin's wife, Praskovia, needed a hysterectomy, the grateful Grand Duke Nicholas paid for the best surgeons in St Petersburg. Praskovia had woken in the night, screaming with pain, thinking that she was suffering from cramps. She had then collapsed while working in the fields. Her husband, by that time fully immersed in the comforts of Court life, may have felt twinges of guilt as he made the six-day journey back to Pokrovskoye to pick her up.

After the operation, Rasputin treated her to a

drozhky

ride around the sights, including the Peter and Paul Fortress and the Winter Palace. But Praskovia was not impressed: âI don't want to live here,' she proclaimed, before taking the first train available back to Tyumen. Rasputin's father, Efim, had been equally underwhelmed by St Petersburg: upon his arrival, he made the sign of the

cross, and left the city within a week.

It was during these early days in the capital that Rasputin met the man who would become one of his most unhinged followers, the monk Iliodor. A celebrated anti-semite, Iliodor led processions carrying giant dolls dressed in Jewish kaftans. At the end of rumbustious ceremonies, the dolls would be burnt. Iliodor was 11 years Rasputin's junior, but, when they met, it was Rasputin who acted like an awe-struck child, putting the grimy fingers of one hand in his mouth and stamping his feet on the spot, as if about to gallop away.