Read My Pins (3 page)

Authors: Madeleine Albright

opal butterfly, Tiny Jewel Box

pearl butterfly, Kenneth Jay Lane

gold butterfly and wreath, Miriam Haskell

amber butterfly, designer unknown

green and violet butterfly, Modital Bijoux

rhinestone butterfly, José & María Barrera

silver and blue butterfly, designer unknown

gray rhinestone butterfly, Ciner.

The pin that began it all.

Serpent, designer unknown.

The

idea of using pins as a diplomatic tool is not found in any State Department manual or in any text chronicling American foreign policy. The truth is that it would never have happened if not for Saddam Hussein.

During President Bill Clinton’s first term (1993–1997), I served as America’s ambassador to the United Nations. This was the period following the first Persian Gulf War, when a U.S.-led coalition rolled back Iraq’s invasion of neighboring Kuwait. As part of the settlement, Iraq was required to accept UN inspections and to provide full disclosure about its nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons programs.

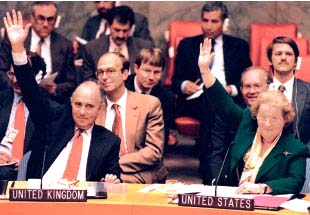

TIMOTHY CLARY/GETTY IMAGES

Voting in the UN Security Council. That is the serpent pin on my jacket.

When Saddam Hussein refused to comply, I had the temerity to criticize him. The government-controlled Iraqi press responded by publishing a poem entitled “To Madeleine Albright, Without Greetings.” The author, in the opening verse, establishes the mood: “Albright, Albright, all right, all right, you are the worst in this night.” He then conjures up an arresting visual image: “Albright, no one can block the road to Jerusalem with a frigate, a ghost, or an elephant.” Now thoroughly warmed up, the poet refers to me as an “unmatched clamor-maker” and an “unparalleled serpent.”

In October 1994, soon after the poem was published, I was scheduled to meet with Iraqi officials. What to wear?

Years earlier, I had purchased a pin in the image of a serpent. I’m not sure why, because I loathe snakes. I shudder when I see one slithering through the grass on my farm in Virginia. Still, when I came across the serpent pin in a favorite shop in Washington, D.C., I couldn’t resist. It’s a small piece, showing the reptile coiled around a branch, a tiny diamond hanging from its mouth.

While preparing to meet the Iraqis, I remembered the pin and decided to wear it. I didn’t consider the gesture a big deal and doubted that the Iraqis even made the connection. However, upon leaving the meeting, I encountered a member of the UN press corps who was familiar with the poem; she asked why I had chosen to wear that particular pin. As the television cameras zoomed in on the brooch, I smiled and said that it was just my way of sending a message.

A second pin, this of a blue bird, reinforced my approach. As with the snake pin, I had purchased it because of its intrinsic appeal, without any extraordinary use in mind. Until the twenty-fourth of February 1996, I wore the pin with the bird’s head soaring upward. On the afternoon of that tragic day, Cuban fighter pilots shot down two unarmed civilian aircraft over international waters between

Cuba and Florida. Three American citizens and one legal resident were killed. The Cubans knew they were attacking civilian planes yet gave no warning, and in the official transcripts they boasted about destroying the

cojones

of their victims.

RICHARD DREW/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Blue bird, Anton Lachmann.

RICHARD DREW/ASSOCIATED PRESS

I used blunt words to express anger and sadness when, in 1996, airplanes carrying four Cuban-American fliers were shot down off the coast of Florida. My blue bird pin reflected my mood.

At a press conference, I denounced both the crime and the perpetrators. I was especially angered by the macho celebration at the time of the killings. “This is not

cojones

,” I said, “it is cowardice.” To illustrate my feelings, I wore the bird pin with its head pointing down, in mourning for the free-spirited Cuban-American fliers. Because my comment departed from the niceties of normal diplomatic discourse, it caused an uproar in New York and Washington; for the same reason, it was welcomed in Miami. As a rule, I prefer polite talk, but there are moments when only plain speaking will do.

COURTESY OF PRESIDENT GEORGE H.W. BUSH

My first trip as secretary of state was to Texas, where I was greeted warmly by former President George H.W. Bush and Barbara Bush at their Houston home. In the background is Millie, their pet springer spaniel, author of

Millie’s Book: As Dictated to Barbara Bush

, a 1991 best-seller. My pin, hard to see, is an eagle with a pearl.

Before long, and without intending it, I found that jewelry had become part of my personal diplomatic arsenal. Former President George H.W. Bush had been known for saying, “Read my lips.” I began urging colleagues and reporters to “Read my pins.”

While teaching at Georgetown University, I tell my students that the purpose of foreign policy is to persuade others to do what we want or, better yet, to want what we want. To accomplish this, a president or secretary of state has a range of tools that includes military force at one end of the spectrum and words of reason at the other. In between are such instruments as diplomacy, economic sanctions, foreign aid, and trade. Compared to these, the brooch or pin may seem trivial.

COURTESY OF PRESIDENT GEORGE H.W. BUSH

Sun, Steinmetz Diamonds.

I do not claim too much, but I do believe the right symbol at the correct time can add warmth or needed edge to a relationship. A foreign dignitary standing alongside me at a press conference would be happier to see a bright, shining sun attached to my

jacket than a menacing wasp. I felt it worthwhile, moreover, to inject an element of humor and spice into the diplomatic routine. The world has had its share of power ties; the time seemed right for the mute eloquence of pins with attitude.

Crystal fly, Christian Dior;

green and blue rhinestone bees, Ciner;

turquoise bee, Walter Lampl;