Read My Pins (5 page)

Authors: Madeleine Albright

Castle, LJ.

Indian elephant, DeNicola.

From early times, the rulers of India were encouraged to accumulate stockpiles of jewels to enhance their reputations and to outpace potential rivals. They did so not only through taxation but also through wars of conquest, supported by plunder. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the word “loot” is derived from a Hindi verb (

lūt

). When, in 1293, a Venetian traveler visited the king of Malabar in southern India, he found a man so wealthy that even his loincloth (set with emeralds, sapphires, and rubies) was worth a fortune. During the Mogul Empire, the men in a maharaja’s court wore ornate necklaces, bracelets, and rings; the court’s horses and elephants were outfitted with golden tassels and helmets, jewel-laden saddles and anklets, and—in the case of elephants—gold bands around their tusks.

Such wealth did not go unnoticed by foreign visitors. The capitals of Renaissance Europe possessed dazzling assets but lacked one vital ingredient: an indigenous source of gems. The desire to establish a reliable supply line was a major contributor to the Age of Exploration. Christopher Columbus sailed west in search of the mysterious East, inspired by his heavily annotated copy of Marco Polo’s journal, which promised mighty palaces “all roofed with the finest gold.” Though he discovered no golden roofs, Columbus nevertheless thought he had reached Asia; sailors less eager for a shortcut actually did. Guiding their fleets around the Cape of Good Hope, these merchant adventurers established their presence along India’s coast.

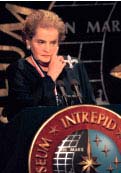

Giving an important speech on Bosnia at the Intrepid Sea, Air, and Space Museum in New York, 1997. I wore a fleur-de-lis, then a part of Bosnia’s state flag. As is evident from the Queen Mother’s crown (

below

), the fleur-de-lis was also popular among European royalty.

ADAM NADEL/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Rhinestone fleur-de-lis, designer unknown; gold fleur-de-lis, Sofie.

COURTESY OF THE ROYAL COLLECTION © 2009 HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II

State crown featuring the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond.

Courtesy of the Royal Collection, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

For several centuries, European traders competed for the favor of the subcontinent’s leading families. The difficulty was how to bribe rulers who were already so rich. For a time, Portuguese merchants had the advantage because their offerings were novel: Colombian emeralds and Mozambican gold, amber, and ivory. Frustrated suitors eventually realized, however, that gift-giving is not the only means of persuasion.

By the start of the nineteenth century, the power of the Mogul dynasty was waning just as Great Britain’s might was waxing. The ambition of Queen Victoria, the increased strength of Her Majesty’s navy, and the skill and aggression of English traders forced India into a role it never wanted: the jewel in the British Empire’s crown. The decisive blow came when, in 1849, the East India Trading Company gained control of Lahore, capital of Punjab. Most prominent among the riches claimed by the company and forwarded as

a tribute to the Queen was an enormous diamond, the incomparable Koh-i-Noor, or “mountain of light.”

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

The Hope diamond.

Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History

.

In the British capital, crowds rushed to see the Koh-i-Noor, but many Londoners were disappointed at its seeming lack of brilliance. Similarly unimpressed, the Queen’s consort, Prince Albert, ordered the piece recut. In little more than a month, the craftsmen produced a beautiful shallow oval. Victoria subsequently wore the polished diamond in a brooch, in a tiara, and as the center of a diadem fashioned by Garrard, the crown jeweler. The gem was later placed in a Maltese cross at the front of the crown of Queen Elizabeth—known to my generation as the Queen Mum—and displayed at her state funeral in the spring of 2002.

The British crown jewels exemplify the connection between perceptions of national glory and the appreciation of valuable stones. This linkage transcends the borders of time, religion, geography, and culture. A traveler today, with sufficient time and the right access, could view everything from the large Manchurian pearls of China’s Qing dynasty to the treasures of the pharaohs, from the crown jewels of Ethiopia to the imperial possessions of the Holy Roman and Austro-Hungarian empires.

In my own travels, I have visited the Tower of London, the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo, the National History Museum of Romania, and the Louvre, where what little remains of the French crown jewels is on display. The majority of the French pieces were either lost in the Revolution or sold later to discourage attempts at restoring the Bourbon dynasty. As one radical parliamentarian exclaimed, “Without a crown, no need for a king.”

The United States, of course, has never desired a crowned head and thus has no crown jewels—though the Smithsonian Institution has the Hope diamond and other extraordinary gems. Early Americans provided proof that jewelry is not the province solely of

royalty. American Indians were skilled at fashioning white, purple, and black beads out of the shells of periwinkles and clams. The beads, known as wampum, were used to record treaties and for other purposes both spiritual and practical. Like a royal crown, beaded headpieces, necklaces, and belts were employed by American tribes to connote leadership status; as with other jewels, wampum might be exchanged to acquire goods, express friendship, pay reparations, or facilitate peace.

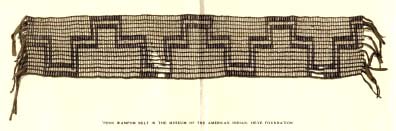

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

This wampum belt, sometimes referred to as the “Freedom” belt, is presumed to have been given to William Penn by the Lenape, or Delaware, Nation, as early as 1682.

Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian

.

For the New World’s European settlers, wampum served as legal tender alongside the coins brought from their homelands. Ever alert for ways to push the natives aside, the settlers learned quickly that the more wampum they accumulated, the easier it would be to buy local land. In the most famous transaction, Peter Minuit, an employee of the Dutch West India Company, purchased Manhattan and later Staten Island for a modest amount of wampum, fabric, and farming implements. The Norwalk Indians accepted a comparable bargain in Connecticut, selling much of what is now Fairfield County.

As these examples suggest, jewelry has played a colorful part in the evolution of world affairs. Because precious stones tend to inspire both admiration and greed, leaders have found convenient excuses for seeking them and have used them to impress crowds, reward friends, deprive foes, forge alliances, and justify war. Jewels may find their highest expression in the decorative arts, but they have also earned a place in the art of the possible.