Reading Rilke

Authors: William H. Gass

Also by William H. Gass

FICTION

Omensetter’s Luck

In the Heart of the Heart of the Country

Willie Master’s Lonesome Wife

The Tunnel

Cartesian Sonata

NONFICTION

Fiction and the Figures of Life

On Being Blue

The World Within the Word

The Habitations of the Word

Finding a Form

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright © 1999 by William H. Gass

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Gass, William H., [date]

Reading Rilke : reflections on the problems of translation / by William H. Gass.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-8041-5092-7

1. Rilke, Rainer Maria, 1875–1926—Translating. 2. Rilke, Rainer Maria, 1875–1926. Duineser Elegien. 3. Translating and interpreting. 4. Rilke, Rainer Maria, 1875–1926. 5. Authors, German—20th century—Biography. I. Title.

PT2635. I65Z

831′.912—dc21

98-50291

v3.1

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO HEIDE ZIEGLER WITH LOVE AND GRATITUDE

.

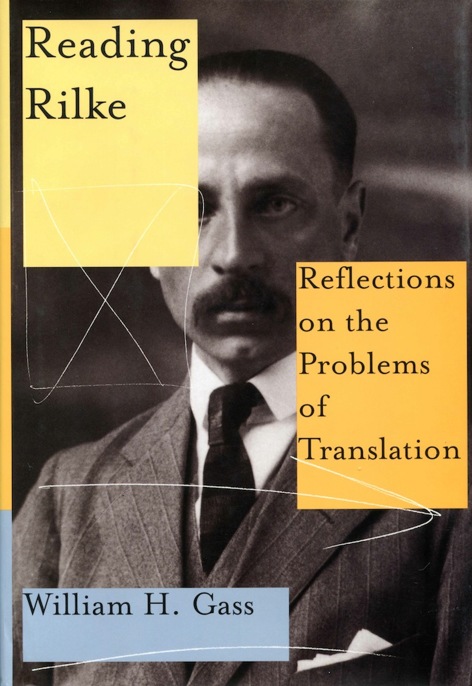

Self-Portrait from the Year 1906

The distinction of an old, long-noble race

in the heavy arches of the eyebrows.

In the blue eyes, childhood’s anxious

shy look still, not a waiter’s servility

yet feminine, as one who endures.

The mouth made as a mouth is, wide and straight,

not persuasive, yet not unwilling to speak out

if required. A not inferior forehead,

still most comfortable when bent, shading the self.

This, as a countenance, scarcely configured;

never, in either suffering or elation,

brought together for a real achievement;

yet as if, from far away, out of scattered things,

a serious and enduring work were being planned.

“Selbstbildnis aus dem Jahre 1906,” Paris, Spring 1906

CONTENTS

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Poems Translated in the Text

Other Than the

Duino Elegies

Acknowledgments

Lifeleading

Transreading

Ein Gott Vermags

Inhalation in a God

Schade

The Grace of Great Things

Erect No Memorial Stone

The

Duino Elegies

of Rainer Maria Rilke

Notes

Bibliography

POEMS TRANSLATED IN THE TEXT

OTHER THAN THE

DUINO ELEGIES

Self-Portrait from the Year 1906

Selbstbildnis aus dem Jahre 1906

Rilke’s epitaph

Rose, oh reiner Widerspruch

The Bowl of Roses

Die Rosenschale

from

In Celebration of Myself

Mir zu Feier

A Youthful Portrait of My Father

Jugend-Bildnis meines Vaters

Parting

Abschied

III. 6–7 of

The Book of Hours

Das Stundenbach

Autumn

Herbst

Autumn Day

Herbstag

To Music

An die Musik

The Lace, 11

Die Spitze

, 11

Buddha

Buddha

The Panther

Der Panther

Rilke’s last poem, untitled

The Swan

Der Schwan

Put My Eyes Out, 11.7 of

The Book of Hours

Lösch mir die Augen

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 1, 3

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 1, 1

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 1, 2

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 11, 13

Torso of an Archaic Apollo

Archaïscher Torso Apollos

Lament

Klage

The Spanish Trilogy, 1

Die spanische Trilogie

The Great Night

Die grosse Nacht

Requiem for a Friend

Requiem für eine Freundin

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 11, 1

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 11, 29

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 11, 12

Blue Hydrangea

Blaue Hortensie

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 1, 13

Turning-Point

Wendung

Death

Der Tod

Tell Us, Poet, What Do You Do?

Oh sage, Dichter, was du tust?

“Man Must Die Because He Has Known Them”

“

Man muss sterben weil man sie kennt

”

Puppet Theater

Marionettentheater

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 1, 5

Sonnets to Orpheus

, 1, 15

The Death of the Poet

Der Tod des Dichters

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Heide Ziegler, to whom this book is lovingly dedicated, spent much of her valuable time and energy discussing with me the meanings of the

Duino Elegies

, giving me valuable background information, advising me on strategies, correcting many of my mistakes (impossible to catch them all), and patiently reading and rereading my revisions. This book is half hers. No doubt the better half.

I am also indebted to all those who, before me, have tried to find their way through these difficult poems, and beaten a better path … a path from which, so often, I fear I have strayed.

Early versions of a few of these poems were published in

The American Poetry Review

,

Conjunctions

, and

River Styx

. The first three

Sonnets to Orpheus

, Part 1, were published in

The Chelsea Review

. I have also cannibalized from texts published in

The Nation

and in

The Philosophy of Erotic Love

, a collection from the University of Kansas Press edited by Robert Solomon and Kathleen Higgens.

The poet himself is as close to me as any human being has ever been; not because he has allowed himself—now a shade—at last to be loved; and not because I have been able to obey the stern command from his archaic torso of Apollo to change my life, nor because his person was always so admirable it had to be imitated; but because his work has taught me what real art

ought to be; how it can matter to a life through its lifetime; how commitment can course like blood through the body of your words until the writing stirs, rises, opens its eyes; and, finally, because his work allows me to measure what we call achievement: how tall his is, how small mine.

LIFELEADING

Open-eyed, Rainer Maria Rilke died in the arms of his doctor on December 29, 1926. The leukemia which killed him had been almost reluctantly diagnosed, and had struck like a storm, after a period of gathering clouds. Ulcerous sores appeared in his mouth, pain troubled his stomach and intestines, he slept a lot when his body let him, his spirit was weighed down by depression, while physically he became as thin and fluttery as a leaf. Since, according to the gloom that naturally descended on him, Rilke’s creative life was over, he undertook translations during his last months: of Valéry in particular—“Eupalinos,” “The Cemetery by the Sea”—and composed his epitaph, too, invoking the flower he so devotedly tended.

ROSE

,

O PURE CONTRADICTION

,

DESIRE

TO BE NO ONE’S SLEEP BENEATH SO MANY LIDS

.

The myth concerning the onset of his illness was, even among his myths, the most remarkable. To honor a visitor, the Egyptian beauty Nimet Eloui, Rilke gathered some roses from his garden. While doing so, he pricked his hand on a thorn. This small wound failed to heal, grew rapidly worse, soon his entire arm was swollen, and his other arm became affected as well. According to the preferred story, this was the way Rilke’s disease

announced itself, although Ralph Freedman, his judicious and most recent biographer, puts that melancholy event more than a year earlier.

Roses climb his life as if he were their trellis. Turn the clock back twenty-four years to 1900. Rilke is a guest at Worpswede, an artists’ colony near Bremen, and it is there he has made the acquaintance of the painter Paula Becker and his future wife, Clara Westhoff. One bright Sunday morning, in a romantic mood, Rilke brings his new friends a few flowers, and writes about the gesture in his diary:

I invented a new form of caress: placing a rose gently on a closed eye until its coolness can no longer be felt; only the gentle petal will continue to rest on the eyelid like sleep just before dawn.

1

The poet never forgets a metaphor. Nor do his friends forget the poet’s passions. Move on to 1907 now, when, in Capri, Rilke composes “The Bowl of Roses,” beginning this poem with an abrupt jumble of violent images:

You’ve seen their anger flare, seen two boys

bunch themselves into a ball of animosity

and roll across the ground

like some dumb animal set upon by bees;

you’ve seen those carny barkers, mile-high liars,

the careening tangle of bolting horses,

their upturned eyes and flashing teeth,

as if the skull were peeled back from the mouth.

Bullyboys, actors, tellers of tall tales, runaway horses—fright, force, and falsification—losing composure, pretending, revealing

pain and terror: these are compared to the bowl of roses. Rilke has come from Berlin, where his new publisher, Insel Verlag, has been distressed to discover that Rilke’s former publisher plans to bring out

The Book of Hours

as well as a revised

Cornet

. This does not get the new alliance off to a smooth and trusting start. Moreover, Rilke is broke again. During 1906, the poet had been bankrolled by his friend Karl von der Heydt, who twice generously deposited funds in Rilke’s Paris bank, but Rilke’s habit of staying in deluxe hotels and eating (modestly) in expensive restaurants, his dependence upon porters and maids and trains, had left him holding nothing more than his ticket to Alice Faehndrich’s Villa Discopoli on Capri. Von der Heydt sent him some supplementary funds eventually, but not before making a face. Perhaps these unpleasantries account for the poem’s oddly violent and discordant opening.

But now you know how to forget such things,

for now before you stands the bowl of roses,

unforgettable and wholly filled

with unattainable being and promise,