Real Food (12 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

No one knows how many American cattle have BSE, but many observers fear it is already common. Japan tests every market-bound

animal for BSE, and Britain tests every animal older than twenty-four months. In 2005, the United States tested thirty-seven

thousand of thirty-seven million cattle slaughtered: 1 percent.

3

mad cow disease worries you, choose grass-fed, organic, or bio-dynamic beef.

Humans have been raising pigs for at least ten thousand years and hunting wild boar for much longer. Despite being shunned

by two great religions, pork is the world's most popular meat. The pig has the distinction of being the only mammal whose

skin we eat. "Who can resist the crackling from roast pork?" asks the food writer Anne Dolamore.

4

Crackling!

The word is sure to make southerners wistful about Grandma's Sunday dinners. Perhaps more than any other animal, the pig is

associated with its fat. Irish legend tells that Saint Martin created the pig from a piece of fat, and lard is traditional

in many cuisines, from Europe to China to Indonesia. On the island of Borneo, pork, lard, and rice make up the typical dinner,

and the fat of wild boar— only its fat, not lean meat— is considered the unique source of physical, sexual, and spiritual

vitality. In nineteenth-century America, lard was the fat of choice for frying and baking. Well into the twentieth century,

"lard ruled the kitchen and the palate," says the culinary historian Bruce Kraig.

5

Unlike other animal fats, lard makes a dish on its own. A Tuscan specialty,

lardo,

is nothing more than a ribbon-thin square of lard, cured with salt and rosemary.

That people love pork is no mystery— it's delicious. Pigs are popular with farmers, too: they eat anything, fatten easily,

breed quickly, and work hard. Indeed most farms have more pig labor than pig tasks, and the working pig is happy rummaging

through forests, old orchards, and hedgerows.

Sadly, this is not the picture of pigs on factory farms. Raised indoors in crowded pens, they cannot pursue their natural

impulse to root. Concrete or slatted floors allow for easy removal of manure, but they also cause arthritis and deformed feet.

Factory pigs are deficient in vitamin E and selenium, antioxidants found in pasture.

6

Confined pigs are subject to infections, including a fatal form of gastroenteritis; to stave off illness, farmers feed them

antibiotics. A strain of salmonella found in swine is resistant to an important antibiotic, fluoroquinolone.

7

(Growth hormones may not be used in pigs.)

Under the stress of crowded conditions, pigs bite each other's tails and cause infections. To preempt tail biting, factory

farmers snip off the tails with wire cutters (without anesthetic), leaving a hypersensitive stump which pigs work to keep

away from the teeth of other pigs. This is called

avoidance behavior.

That's the theory, anyway, but a British study in 2003 found that tail docking

increases

tail biting.

8

A happy chicken is up with the dawn, lays an egg in the late morning, and when the farmer opens the little chicken house door,

she heads outside to hunt for insects in the grass. The occasional dust bath— rolling around in dry soil, fluffing the dust

under her feathers— keeps her free of pests. At dusk, the hen goes inside on her own, safe from predators, to her dinner of

grain and oyster shell. That's how our chickens live at the farm. Their contented cooing as they settle for the night is one

of my favorite sounds.

Not long ago I was in a battery chicken house. It is not a memory likely to fade quickly. Dark and dusty, the barn smelled

of ammonia— the sharp, unmistakable odor of uncomposted chicken manure. Stacked in long rows, the wire cages were shorter

than my arm and half as deep. Three hens cowered in each cage, with no room to move around. "These cages were built for

nine

hens," said the farmer, with some pride.

Because they never see the light of day, factory hens lose the natural rhythm essential to egg laying. Instead of sunlight,

artificial lights tell their bodies when to lay eggs. With no room to move, nest, or forage, a hen has nothing to do but eat,

drink, and drop an egg through the wire on a narrow tray or conveyor belt.

Chickens require complete protein, and a good source is insects, grubs, and worms. Factory chicken feed often includes protein

from less savory sources: poultry parts and feathers, rendered cats and dogs, beef fat, and cattle bone meal. In crowded battery

egg operations, pathogens thrive. Salmonella can make its way into factory eggs, usually via cracked shells, but occasionally

before being laid. If the flock is known to be infected, eggs go to the "breakers" market rather than being sold whole. Breakers

are pasteurized and made into liquid egg products for restaurants.

Chickens raised for meat— broilers— are also crammed in dark barns. A typical factory chicken barn is eighteen thousand square

feet with twenty to forty thousand birds. At the lower density of twenty thousand birds, that's less than one square foot

per bird. Crowded like this, chickens become aggressive and peck each other, so farmers cut their beaks off when they're chicks.

Birds are confined and the temperature is kept warm because exercise and generating body heat burn calories, and speedy weight

gain is the goal.

To combat rampant campylobacter, salmonella, and

E. coli,

farmers feed broilers antibiotics like fluoroquinolone, with now familiar effects on antibiotic resistance. Strains of

E. coli

and salmonella no longer respond to tetracycline, and some campylobacter bacteria are resistant to Cipro, the antibiotic of

choice for food-borne illness. In 1989, researchers showed that more antibiotic-resistant strains are found in confinement

hens than in free-range birds.

9

In 2000, the FDA proposed to ban fluoroquinolone for use on poultry, but the effort has been stalled by drug companies.

Meanwhile, two large chicken producers (Tyson and Perdue) stopped using fluoroquinolone voluntarily. If a bird does happen

to carry pathogens, the meat can be contaminated (usually from stray fecal matter) on high-speed evisceration lines. Industrial

agriculture, of course, has the answer: your chicken breast is bleached with chlorine.

FACTORY CHICKEN AND CAMPYLOBACTER

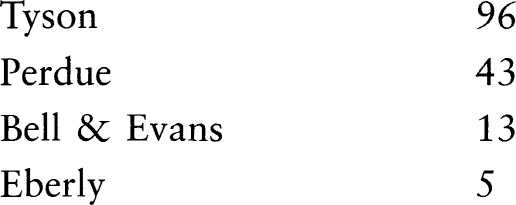

Researchers tested four chicken brands— two conventional (Tyson, Perdue) and two antibiotic-free (Bell & Evans, Eberly)— for

strains of campylobacter resistant to the antibiotic fluoroquinolone. Tyson and Perdue had stopped using fluoroquinolone a

year before the test, showing that strains persist.

% of Chickens Carrying Drug-Resistant Campylobacter

Bacteria

Source: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2005.

Apologists for industrial farming repeat one argument like a mantra: this food is cheap, and people want it that way. But

the real costs are seldom reckoned. According to

Environmental Health

Perspectives,

"Industrial agriculture depends on expensive inputs from off the farm . . . many of which generate wastes that harm the environment;

it uses large quantities of nonrenewable fossil fuels; and it tends toward concentration of production, driving out small

producers and undermining rural communities."

10

Small and independent farms are disappearing. The beef, pork, and poultry industries, once made up of thousands of family

farms, are increasingly concentrated. In Iowa, the number of hog farms dropped from 64,500 in 1980 to 10,500 in 2000, while

the number of hogs— about 15 million— stayed level. Cornell University says that New York State will lose 6,000 dairy farms

in the next fifteen years.

When counted honestly, the financial costs of industrial agriculture mount quickly. Every American foots the bill to clean

up water polluted by manure lagoons. The EPA says that waste water from farms contains nitrogen, pathogens, heavy metals,

hormones, and antibiotics. Excess nitrogen has created a "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico the size of New Jersey. Eighty

percent of the American grain crop, which requires heavy doses of nitrogen and pesticides, is fed to livestock, even though

they could be eating grass. Industrial cattle eat corn, wheat, soy, and cottonseed oil because this feed is subsidized. From

1995 to 2004, taxpayers spent ninety-one billion dollars on these four crops alone.

The dismaying fact is that industrial farming is a net loss. As Richard Manning writes in

Against the Grain,

in 1940, the average American farm used one calorie in fossil fuels to raise 2.3 calories of food. By 1974 (the most recent

figures available), the ratio was 1:1,

before

adding the cost of processing food or transportation. Today a farmer spends thirty-five calories in fossil fuels to produce

just one calorie of feedlot beef and sixty-eight calories for a calorie of pork.

No, Virginia— this food ain't cheap.

Why Grass Is Best (and I Don't Mean for Tennis)

All flesh is grass.

—Isaiah

JOEL SALATIN is AN irrepressible evangelist for traditional animal husbandry. Salatin believes the assembly-line logic of

industrial agriculture has turned farmers from independent yeomen into "serfs," slaving for food industry masters to produce

cheap food, fast. A strapping man with charisma to spare, Salatin surprises no one when he rejects the role of serf. He prefers

to raise beef, poultry, and eggs as God intended. An enthusiastic Christian, capitalist, libertarian, — Isaiah and environmentalist,

he likes to count former vegetarians among his customers. When I'm on his farm, or at a farmers' market where I can buy his

meat, I'm one of them.

A born sloganeer, Salatin calls his product

salad bar beef.

He knows the term makes you do a double take. It's the cattle, of course, who eat at the salad bar, a mix of fescue, orchard

grass, red clover, bluegrass— whatever grows in Swoope, Virginia. Salatin's definition of

salad bar beef,

however, goes well beyond grazing. Salad bar beef is never fed any grain, corn, soybeans, antibiotics, or hormones. It's lean,

tender, and tasty— never bland or gamey. It's nutritionally superior to beef fattened on grain, with more omega-3 fats, beta-carotene,

and vitamin E. It's seasonal, too. Industrial beef is bred year-round, but on Salatin's farm, calves are born in late spring,

amid the dandelions, as he likes to say— never in icy January.

Last but not least, salad bar beef is slaughtered, butchered, and sold locally. Even when food lovers in far-off cities call

the farm to order meat, having read about Salatin's farm in

Gourmet

or the

New York Times,

he refuses to ship his food. Salatin is a purist, to be sure. Fine— the world needs purists. If everyone raised salad bar

beef, Salatin says, "City folks could enjoy beef without a guilty conscience."

Farmers who raise animals on pasture (being modest types) call themselves grass farmers, because "all they do" is grow grass.

The method is ingeniously simple: instead of taking feed to animals, grass farmers let animals go to the feed. The most nutritious

pasture is fast-growing, adolescent grass. When the animals have trimmed the best of the new growth, farmers move them to

fresh pasture. It's called rotational grazing, and it works, says one farmer, because "grass doesn't like to walk around,

and cows do."

Nature is their inspiration. Wild herbivores like zebras travel in herds and move frequently for fresh forage, leaving yesterday's

manure behind— just what grass farmers do with animals. In the wild, flocks of birds follow the zebras, while grass farmers

send poultry in after livestock. As the grass recovers from being grazed by ruminants, poultry scratch at cow pats and aerate

the manure (so it decomposes) while they grow fat or lay eggs eating protein-rich fly larvae.

Grass farming is profitable. Farmers save on labor, repairs, fuel, oil, seed, fertilizer, pesticides, and vet bills. Grazing

makes use of marginal land and produces excellent yields, directly related to pasture health and how often animals move. Cattle

digestion is complex, but this general rule applies: cattle gain weight on grain; they make more milk and cream eating roughage,

that is, grass and hay. For beef farmers, then, grass means a slower return— cattle fatten much faster on grain— but the farmer

also has lower feed costs, more nutritious beef, and a higher price in the right markets. For dairy farmers, grass farming

is remarkably efficient. Cream from grass-fed cows contains more omega-3 fats and vitamin A, and spring and fall grass yields

significantly more cream. In one survey, Vermont graziers earned more per cow than even the most profitable confinement dairies.

The environment benefits from grazing, too. Industrial grain and soybeans for cattle feed are grown with fertilizer and pesticides,

but grass and hay are easily grown without chemicals. Well-grazed pastures have more diverse plants than fallow land. The

constant cutting and regrowth of grazing stimulates dense root growth, improving soil fertility and preventing erosion, and

because cows walk around, manure is spread evenly, reducing nitrogen runoff.