Real Food (15 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Grain-finished

beef was raised on grass and fattened with grain. I can live with a little silage or grain in my beef— even a wild steer would

have eaten a few seed heads— but if you're a purist, look for the label

100 percent grass-fed.

Pastured

applies to pork, poultry, and eggs when animals are raised on pasture. "Grass-fed" bacon and eggs is not correct, because

a diet of grass isn't enough for these omnivores. Like humans, pigs and chicken need complete protein. Pastured chickens eat

corn, insects, and sour milk as well as grass. On eggs or poultry, the label

vegetarian feed

is misleading. It means chickens were not fed other ground-up chickens— and that's good. But chickens are not natural vegetarians.

What it

does

mean is the birds never went outside; if they had, they might have eaten a grub or two.

Free-range

poultry and eggs says nothing about grass. It means the birds aren't in cages, but they may be in barns or on bare dirt. Grass

is the key source of beta-carotene, CLA, and omega-3 fats in pastured poultry and eggs.

As I've mentioned, there is no single diet for the not-picky, omnivorous pig. Swine will eat different foods on every farm:

acorns and apples here, coconut and corn there. Whey-fed pork is popular on dairies because farmers have plenty of protein-rich

whey to spare after cheese making. Pigs are sometimes raised in barns on deep straw; this is better than industrial pork,

but ideally pigs root outside in meadows or woodland, usually with huts for shelter. Good fencing is the key; it is not easy

to keep pigs from running riot. If a local farmer raises pastured pork, count yourself lucky and eat up.

LETTING PIGS GO HOG WILD

Beverley Eggleston of EcoFriendly Foods in Moneta, Virginia, explains how pigs like to live: "Wild hogs are foragers with

a great sense of smell; they root with strong snouts. Pig and plow come from the same root word. You will never find a happier

pig than one up to his shoulders in dirt, chewing on wild potatoes or other roots. I've seen pigs flip big rocks over with

their noses, just for fun. Our farmers raise hogs in a setting that allows them to run around and dig. Because pigs literally

tear up the landscape, it's important to use that to the advantage of the farm, not the destruction. The industry's solution

is to put the pigs on concrete; this makes a boring and hard life for the pig. On the other hand, you can't really put them

on pasture and expect the grass to last. The obvious solution is to put the pigs in a place that you want to dig up anyway."

Organic

is legally defined. It means the food was produced without synthetic fertilizer, antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, genetically

engineered ingredients, and irradiation. Organic does

not

mean animals were grass-fed or pastured. Organic beef, pork, and poultry eat organic grain, but most commercial versions are

not raised on grass, or their access to pasture is minimal.

Conversely,

grass-fed

and

pastured

don't mean animals were raised to organic standards, but the grass farmer who uses antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, or genetically

engineered foods is rare. The label

natural

says nothing about the animal's diet. It means the product contains no artificial flavor or color, chemical preservative,

or any other artificial ingredient. This weasley term is widely used. According to the USD A, "all fresh meat" qualifies as

"natural."

In the 1950s, when corn-fed beef became trendy, good cooks adjusted their recipes— or so I imagine. Similarly, you may need

to tweak things a bit for lean grass-fed beef. Many people believe that lean meat is bound to be tough, but the grass-farming

expert Jo Robinson says that fat marbling accounts for only 10 percent of variation in tenderness. Other factors are breed,

cut, age, and sex of the animal, calcium levels in the soil (and thus the meat) whether it was stressed before slaughter,

how it was chilled (too cold and it toughens), how long it was hung, and, of course, how you cook it.

"We would no sooner cook salad bar beef like fat beef than we would cook venison like fish," says Mr. Grass himself, Joel

Salatin. The chief risk with grass-fed beef and bison is overcooking. At high temperatures, the proteins in meat contract

and toughen. Grass-fed steaks cook in half the time of a grain-fed steak. Other things being equal, the lower the final temperature

of the meat, the more tender it will be.

That said, there are two approaches: cook it very quickly and keep it rare; or cook it slowly, with moisture. For steak, the

food writer Betty Fussell, an expert on beef, favors quick cooking over high heat. "Rare should be really rare," she says.

"If you like a buttery texture, add a pat of herbed butter to the cooked steak, French-style." Some cooks marinate steak first.

With other cuts, cook it low and slow, with moisture. As with any meat, the less tender cuts, such as chuck steak, benefit

from braising.

You may need to make other minor adjustments with grass-fed meat. When you calculate how many people a roast will feed, you

don't need to allow for shrinkage— grass-fed tenderloin, for example, is so lean that very little fat is lost— but the temperature

should be lower and the cooking time shorter. When browning grass-fed ground beef for chili or spaghetti sauce, I find it

helpful to use a fair bit of olive oil.

Industrial beef is fattier than traditional beef, but with pork, the opposite is true. Commercial pork has been bred very

lean— that's why kitchen tricks to prevent dry meat are often called for— and traditional pork is richer. The industrial pig

is typically 56 percent lean, while Bill Niman, founder of Niman Ranch, favors 48 to 51 percent lean pork. A fatter and moderately

muscled pig has more flavor.

Many small farmers raise a standard commercial breed like the Large White. A Yorkshire native, the Large White has been a

registered breed in England since 1884, and it has proved adaptable on modern farms. It does well in confinement and produces

a great deal of bacon and other cuts from its straight back and large loin. Other farmers favor rare traditional breeds like

Gloucester Old Spot, Large Blacks, and Tamworths, which are often richer than conventional breeds. A loin of pastured Gloucester

Old Spot requires very little doctoring. A little olive oil, salt, rosemary, and a very hot oven will do nicely.

Pastured chicken has a rich flavor and firm texture compared with flabby and insipid factory chicken. Stock made from pastured

chicken is superior, too. I suspect that's because a chicken that gets exercise on well-managed pasture and grows slowly has

more gelatin in its joints, more amino acids (protein) in its meat, and more minerals in its bones. In other words, a pastured

chicken is a more complex and dense creature, and that makes for richer, tastier, and more nutritious stock.

Recently, poultry breeds have won more attention from farmers and chefs. The typical commercial chicken is a large-breasted

Cornish cross, and many small farmers raise it on pasture. Other farmers raise traditional, slow-growing breeds such as Redbro,

Mastergris, or GrisBarre, which tend to be leaner, with darker meat and rich flavor. Traditional turkey breeds, once endangered,

are also making a comeback. Look for Standard Bronze, Narragansett, Royal Palm, Bourbon Red, and Black Slate.

Cooking pastured poultry is simple: just watch the leaner breeds to avoid dry meat. They benefit from shorter roasting times

and the sort of tricks used on wild fowl, such as wrapping with bacon. I'm a fan of traditional turkey breeds, but for roast

chicken, I find some of the older breeds a bit too skinny, so I tend to buy a commercial breed, like a Cornish cross. When

raised on pasture, they seem to have the right combination of meat, juice, flavor, and tenderness.

How Our Brains Grew Fat on Fish

WHAT WOULD YOU SAY to a six-year-old who asked you: where do farmers come from? Perhaps you would tell a bedtime story like

this: Back in the Stone Age, our ancestors were skillful hunter-gatherers. They gnawed on marrow bones, dug tubers, gathered

seeds, cracked nuts, and speared fish. Life was good. Over time, however, the smarter ones perceived that a little planning

and organization would yield a more reliable food supply, one that could be more easily stored for a rainy day and shared

with others. These innovative deer hunters and berry pickers began to tame smaller wild cows and plant larger seeds of wild

grass. Eventually, the tribes who were best at these new tricks put aside their restless ways and settled down in villages

to harvest grain and herd animals for milk and meat. They became farmers.

Richard Manning has a subtly different take on what he calls the "just so" story of the rise of agriculture. He believes fishing

was the second-oldest profession, not farming. In

Against the

Grain,

Manning imagines early humans were keen to be near a steady supply of eels, salmon, and other migrating fish. They looked

for neighborhoods with good water and rested there to wait for hordes of fat seasonal fish; only

then

did they start to tend, guide, herd, and harvest wildlife in the backyard. While REAL FISH 123 waiting for the river mouth

to disgorge fish, the Cro-Magnon had time to paint the mighty salmon on cave walls, a sure sign of its importance.

Fishing man— call him

Homo

piscator

— fills in part of the story Fishing of the transition from swinging in the trees (like our fruit-loving primate cousins)

to becoming hunter-gatherers and, eventually, farmers. Paleoanthropologists have long puzzled over the "missing link"— the

ancestor we share with chimpanzees and gorillas, whose bones (mysteriously) are not found in the fossil record. Where did

they live, how did they move about, what did they eat? No one knows.

In 1960, the marine biologist Alister Hardy offered a novel theory about the era after we came down from the trees and before

we settled on the plains. Suppose we spent a few million years living in the shallow waters of the sea, like aquatic mammals

including the dolphin, hippo, and sea cow? According to Elaine Morgan in

The Descent of Woman,

the quasi-aquatic ape hypothesis could explain a number of downright peculiar human features: nude skin, subcutaneous fat,

always plump breasts, how newborns love to swim, why we have sex face-to-face . . . I could go on about the ways we are unusual

among primates. But for our purposes, the most compelling thing about the idea that our ancestors once lived in the water

is our dramatic and indisputable dependence on fish.

If you've glanced at a biology text recently, you'll know that the river ape idea is not widely accepted. However, the experts

do agree our taste for fish is ancient. Many fossils tell us that some two million years ago, at least three hominid species

lived near the huge freshwater lakes of the East African Rift Valley. Each had its niche. The ones with broad, flat molars

apparently ate a plant-based, high-fiber diet; another group, with smaller teeth, ate mostly small fruit, berries, and the

occasional egg or rodent. The third species, of course, was our very own

Homo habilis.

Dubbed "handy man" for the tools he used, including fishing gear like spears and nets, he was an omnivore— and loved fish.

Whether we lived in it or near it, water offered easy access to DHA and EPA, omega-3 fats essential to visual, mental, metabolic,

and hormonal function found only in fish. The body can make its own DHA and EPA from another omega-3 fat found in plants,

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), but the conversion of ALA to DHA and EPA is inefficient. Making DHA and EPA requires vitamin B

6

, magnesium, calcium, and zinc; it is hindered by trans fats, cortisol, alcohol, and sugar.

1

Moreover, the plant sources of ALA— walnut, flaxseed, and canola oil, and a weed called purslane— were not abundant in the

Stone Age. Then, as now, the best source of these vital fats is fish. This is a dilemma for vegetarians; in the future, DHA

and EPA supplements made from algae may solve it.

DHA and EPA are vital to the brain. Like bone marrow, which helped our brains grow much bigger and faster than the brains

of leaf eaters, fish was brain food. Recall that the brain is 60 percent fat;

half

the fat is DHA.

2

Dr. Andrew Stoll puts it bluntly in

The

Omega-3 Connection,

"Without large amounts of DHA . . . we might not have evolved at all." No wonder the search for fish and seafood is universal.

The overwhelming bulk of the human family has settled near sea shores and river mouths. The exceptions— landlocked and mountain

people— go to great lengths to trade with fishing groups for seafood.

3

Like the bonobo— our closest relative, a playful creature that likes to catch shrimp with its hands—

Homo

sapiens

is a water-loving ape.

Life After Salmon: Obesity, Diabetes, and Heart Disease

THE KLAMATH RIVER RUNS through the mountains of northwest California, passing through the town of Happy Camp, home of REAL

FISH 125 the Karuk tribe. Once the Klamath River ran thick with salmon, which the Karuks devoured at every meal, each one

putting away more than one pound of fish daily. Then, in the 1960s and '70s, hydroelectric dams stopped the water, the salmon

disappeared, and the Karuks turned to industrial foods.

4

When wild salmon were plentiful, diabetes and heart disease were rare. Not now. The percentage of tribe members with diabetes

has risen from near zero to 12 percent, almost twice the national average. Forty percent of the tribe has heart disease— three

times the national rate. "You name them, I got them all," Harold Tripp, a Karuk fisherman, told the

Washington Post.

"I got heart problems. I got the diabetes. I got high cholesterol. I need to lose weight."

That's what can happen when people lose access, almost overnight, to traditional foods and then resort to poor-quality foods.

Like the Karuks, many indigenous Americans have swapped a wholesome diet for cheap, ubiquitous industrial foods. Health takes

a double hit; the new industrial diet causes the very health problems traditional foods can ward off. In this case, the nutritional

mechanisms are well understood. Omega-3 fats in wild salmon prevent the trio of modern diseases— obesity, diabetes, and heart

disease— in multiple ways.

Let's look first at the effects on metabolism, because metabolic disturbances are in many ways the root of all three conditions.

Omega-3 fats regulate blood sugar levels and fat burning. DHA and EPA in particular are directly involved in activating the

expression of genes controlling fat metabolism. For example, mice fed the same number of calories from fish oil are leaner

than those fed corn oil, which is rich in omega-6 fats. People whose muscles are low in omega-3 fats are more likely to be

obese.

Obesity, in turn, leads to diabetes. In the United States today, diabetes and metabolic syndrome— or prediabetes— are epidemic.

"In medical school, I was taught that if you can understand diabetes, you will understand all of medicine," says Dr. Andrew

Stoll, author of

The Omega-3 Connection,

"because those with diabetes fall prey to many other disorders, from cardiac disease to kidney failure to stroke."

What is diabetes? When blood sugar rises, the pancreas secretes the hormone insulin, which signals the muscles to take sugar

from the blood to muscles. Once in the muscle, the sugar has two uses: as immediate energy or as short-term, stored energy,

in the form of glycogen, which marathon runners draw on. In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce insulin at all.

In type 2 diabetes, which accounts for 90 to 95 percent of cases, the pancreas does produce insulin, but the muscles don't

respond; they are "insulin resistant." When the muscles are deaf to insulin, sugar, which is toxic at high levels, gathers

in the blood. Until recently, type 2 diabetes was viewed as an adult disease, and it is still most common in overweight people

over fifty-five, but the rising number of cases in children is a distressing trend. Diabetes, it seems, is not a disease of

age, but of diet. Fish is important, because omega-3 fats decrease insulin resistance.

EAT FISH TO BEAT INFLAMMATION

In type 1 diabetes, the body attacks its own pancreatic cells. Other autoimmune diseases include arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn's,

lupus, colitis, and asthma. A common symptom is chronic excessive inflammation. Omega-3 fats prevent inflammation, and omega-6

fats promote it. Dr. Artemis Simopoulos

(The Omega Diet)

says the protective effect of omega-3 fats on autoimmune kidney disease is "one of the most dramatic effects of omega-3 fats

on any pathology."

5

Diabetes, in turn, leads to heart disease. According to the cardiologist Dr. Arthur Agatston, author of

The South Beach Diet,

half of heart disease patients have metabolic syndrome first. The evidence that omega-3 fats prevent heart disease is robust

and growing. Omega-3 fats reduce the risk of a first heart attack and reduce the risk of sudden death during a heart attack

by 20 to 40 percent.

6

The Physician's Health Study, which followed twenty thousand doctors, found those eating fish as little as once a week were

half as likely to have a fatal heart attack as those who ate fish less than once a month.

7

If you've survived one heart attack, eating fish can prevent another. The

Lancet

reported a study of more than two thousand men who had recovered from a heart attack and were given various instructions on

diet. Advice to reduce fat made no difference in mortality, but men told to eat fatty fish two or three times a week had 29

percent fewer deaths from all causes— the most important measure in epidemiology. Researchers called the effect " significant,"

even after adjusting for ten potentially confounding factors.

8

,

Such studies always cheer me up. All too often, nutritional research is ambiguous, the results are modest, and the advice

is . . . well,

confounding.

Happily, the news on fish is good and getting better. If you're lucky enough— as the Karuks once were— to live near a source

of wild salmon, take advantage of it. Not so lucky? See "Where to Find Real Food".

HOW OMEGA-3 FATS PREVENT HEART DISEASE

• Raise HDL

• Reduce LDL and VLDL (very low density lipoprotein)

9

• Reduce blood pressure by dilating the blood vessels

• Reduce clotting, inflammation, and triglycerides

• Reduce lipoprotein (a),(Lp(a)) which promotes atherosclerosis and blood clots

10

• Reduce risk of death during and after heart attack by reducing irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) through the actions of sodium,

calcium, and potassium ions in heart muscle Are

You Depressed? Try Eating More Fish

MUSCLE AND BONE ARE made of protein and minerals, but the brain is the house that fat built. Our brain is particularly hungry

for the omega-3 fats found in fish. While other organs can manage (if not ideally) on a ratio of four parts omega-6 to one

part omega-3 fats, the brain appears to require equal amounts of each.

11

Why? Unlike other body tissues, the brain can't make DHA and EPA from plant oils like walnuts and flaxseed. In nutrition

jargon, the brain has an "absolute need"— as opposed to a conditional one— for DHA and EPA, which, as we've seen, are found

only in fish. Without adequate DHA and EPA, brain cell membranes don't function properly. Abundant research, much of it recent,

confirms that fish is food for thinking. In 2005, for example, the

Archives of Neurology

reported that older men and women who eat more fish have sharper minds and better memory.

Mental health is one of the most exciting therapeutic applications of fish oil. Omega-3 fats may be as powerful as the drugs

a psychiatrist prescribes, even for serious depression. Population studies, lab work, and clinical experience with depressed

patients all suggest that fish oil can prevent and treat depression. The omega-3 expert Dr. Joseph Hibbeln has found that

differences in depression rates across countries can be predicted by the quantity of fish in the diet. Lab analysis shows

that the brains of depressed people have less omega-3 and more omega-6 fats. Finally, clinical evidence is mounting: doctors

have prescribed omega-3 fats for major depression, postnatal depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, with impressive

results.

The risk to mental health of omega-3 deficiency starts in the womb and continues throughout life. The baby has massive needs

for DHA and EPA, especially in the second half of pregnancy, when growth is mostly due to fat.

12

,

Formula-fed babies and those nursed by omega3-deficient mothers fail to develop proper visual and mental function. Premature

babies are particularly vulnerable because they are poor converters of ALA to DHA and EPA. In one study, premature babies

fed corn oil had underdeveloped eyes and poor vision, while premature babies fed fish oil were virtually identical to full-term,

breast-fed infants. Thus, even when the situation is not ideal— preterm infants are at greater risk in many ways— fish oil

can make a difference.

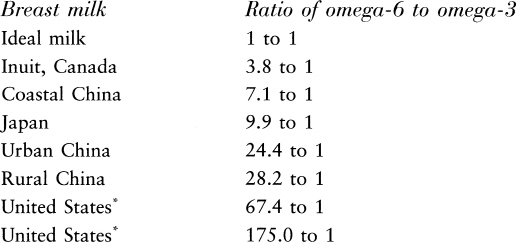

QUALITY OF BREAST MILK IN SAMPLE POPULATIONS

In addition to mental and visual problems in the baby, lack of omega3 fats causes preeclampsia, eclampsia, premature birth,

low birth weight, difficult labor, and postnatal depression. Note how much the quality of breast milk varies, presumably with

fish consumption.