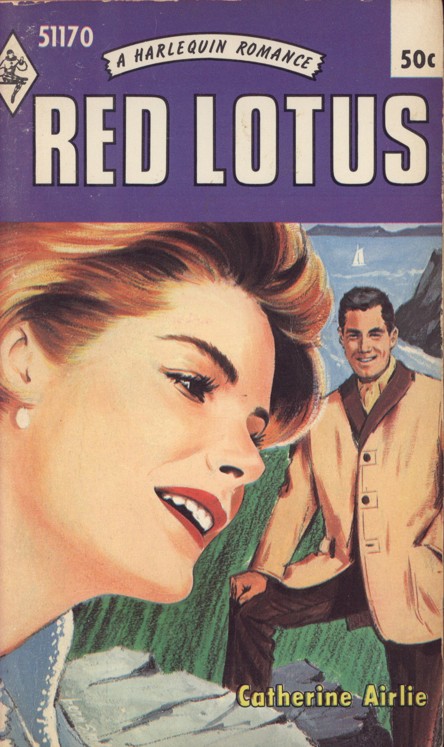

Red Lotus

RED LOTU

S

by CATHERINE AIRLIE

When Felicity landed on the Canary Islands she knew very little about the relations with whom she was going to live. It was something of a shock to her to find that a stranger, Philip Arnold, played an important part on the plantation and in her new life. At first they resented each other; then she grew to admire and love him, but what use was that when his heart was set on someone else?

Printed in the U.S.A.

First published in 1958 by Mills & Boon Limited, 50 Grafton Way, Fitzroy Square, London, England.

Harlequin edition published January, 1968

All the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination of the Author, and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing the same name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the Author, and all the incidents are pure invention.

The Harlequin trade mark, consisting of the word HARLEQUIN® and the portrayal of a Harlequin, is registered in the United States Patent Office and in the Canada Trade Marks Office.

Copyright, ©, 1958, by Catherine Airlie. All rights reserved.

SAN LOZARO VALLEY

THE plane circled the islands and dropped low. From where she sat on the port side, Felicity Stanmore looked down on them, her breath held, her grey-green eyes alight with eager interest. This was the moment for which she had been waiting ever since they had left Madrid: the moment of contact; the moment when she could allow herself to believe that she was really here, at last.

They were a compact group; seven main islands riding an incredibly blue sea, with their smaller satellites clinging to their rugged coastlines like attendant stars. Felicity had always felt attracted by the Canary Islands, where her mother's only brother had lived for most of his adventurous life, but she had not expected the abrupt summons which had reached her in England three months ago on her mother's death and was the reason for her present journey.

"We are your only relatives," Robert Hallam had written. "I shall arrange for your passage out here and you will come as soon as possible. It isn't a matter of charity," he had added in a forthright way which had made her smile at the time, aware that it had given her at least some insight into her uncle's character. "There is a job here that you can do for me."

Several letters had passed to and fro in the interval, but even now, as she approached the islands, Felicity realized that she knew very little about her future and the work she was expected to do.

Sitting forward in her seat, her lips parted in a smile, she had forgotten about the man by her side, the tall, distinguished-looking Spaniard who had boarded the plane at Madrid and taken the only available seat for the journey to Las Palmas.

They had spoken, of course; the desultory conversation

of strangers thrown into close proximity on a long journey, yet she had been instantly aware of the reticence of the well-bred Spaniard, the courtesy which drew up short of curiosity. He had not asked her about herself or why she was on her way to a remote part of Tenerife, which she did not seem to know.

"You are being met," he asked now, "at Las Palmas?" Felicity shook her head.

"No. I understood that I only had to change planes there," she said. "My uncle pointed out that it was quite a simple matter and that I would be met at Santa Cruz."

He looked surprised, as if he considered that she should have been met as soon as the plane touched down on the islands. A gesture of courtesy, perhaps, which a Spaniard would have considered necessary.

"My uncle is a very old man," she explained almost hastily, "and he has not been too well lately. I could not expect him to take a long journey to meet me unless it was really necessary."

He nodded in what she supposed was agreement, although there was still a certain amount of reservation in the dark eyes which met her own. From the moment he had come aboard and taken the vacant seat beside her, Felicity realized, she had been vitally aware of this man His commanding presence, the quick, arrogant turn of the head and the finely-chiselled profile would remain stamped on her memory for a very long time. It was a face not to be easily forgotten, darkly attractive and aristocratically remote, yet in some subtle way she had become aware of his growing interest as the journey had progressed.

She looked down at his fine, beautifully-manicured hands, wondering what he did for a living, if he did anything at all. There was a suggestion of ease about him, of unlimited time to go about the business of gracious living which she was to encounter, again and again, in the weeks ahead as she came to understand the Spanish character and delight in it.

"If you will allow me," he suggested with the utmost courtesy, "when we reach Las Palmas I shall escort you to your plane for Tenerife. I, also, am going there," he added after the briefest hesitation. "It is my home."

"Oh?"

Suddenly she longed to ask him more about his back-

ground, about Tenerife itself, of which she knew so little. His own curiosity had been so pointedly curbed, however, that she hesitated. He had left the decision entirely in her hands whether or not they should probe into each other's past or look forward to the future. Then, just as suddenly, she found herself taking the initiative, aware of time running out and nothing definitely established between them.

"I'm rather nervous about all this," she confessed, looking down on the compact little island beneath them, lying green and placid in the brilliant sunshine. "I've never been abroad before and I have more or less decided to spend the next few years of my life here—or, at least, on Tenerife."

He looked surprised.

"Your uncle is established on the island?" he asked.

"Oh, yes. He has lived there for a very long time. Almost forty years." She hesitated. Did he really want to know this, or was he completely indifferent whether she identified herself or not? The question irked her, because if she were really sensible, she should realize that they were ships that pass in the night, chance acquaintances of a voyage above the clouds which did not hold any permanency or give even a reasonable length of time to foster friendships. "His name is Robert Hallam," she added briefly. "He has banana plantations on the west side of the island, I think."

"In the San Lozaro Valley, in fact." His tone was guarded, his eyes suddenly watchful. "We are practically acquainted," he added after a moment, with the slow smile which was faintly cynical yet only seemed to add to the attraction of the lean, dark face. "I know your uncle quite well. We are—neighbours, shall we say?"

"How—strange!" Felicity exclaimed.

Yet she did not think that it was altogether strange. It all seemed far too inevitable, following a pattern which neither of them could have changed, even if they had wished to do so.

"Perhaps it is not surprising when you consider how small the islands really are," he mused. "We are an isolated group, not quite in mid-Atlantic, but almost so for every practical purpose, clinging to the skirts of Africa, but not African; fiercely proud of our Spanish forebears and looking always towards the mother country of Spain."

"Yet—my uncle is English," Felicity pointed out. "He has never forgotten that."

"He married a Spanish girl."

"Yes. His second wife was Spanish." A small, inexplicable fear crept into Felicity's heart. "Does that make a great deal of difference?"

"Not in your uncle's case, I should say," he assured her lightly. "The Spanish and the English live most amicably on the island. Knowing your uncle, however, I can well see why he sent for you."

She glanced up at him, surprised by the personal nature of the observation.

"Why do you say that?" she asked. "He told me that he had a job waiting for me, but his main reason for asking me to come out here was because my mother has just died." Her voice trembled a little at the memory of that swift and unexpected passing which had left her so utterly alone in England. "We lived rather remotely in Devonshire, in a small village where my father had been vicar for seventeen years," she added, "and my uncle is my only close relative."

"It would be most natural for him to send for you then," her companion acknowledged, "but the job he wanted you to do would be important also. You see," he 'added slowly, "your uncle does not want his family to grow up entirely Spanish. He is, before anything else, an Englishman."

"It's understandable, isn't it?" Felicity said. "He did write and say that he wanted me to come for that reason." He smiled a little.

"The leavening influence!" he mused. "You may find your task difficult at first, Señorita

"My name is Felicity Stanmore," Felicity supplied when he paused expectantly. "My mother and Robert Hallam were brother and sister."

He looked at her for a full minute before he said: "In a good many ways you are like Señor Hallam." Felicity turned eagerly towards him.

"Do you know him very well?" she asked.

"Not very well."

There had been the slightest hesitation before he had made reply, the initial reserve raised like an abrupt bar-

rier between them, but already they had come a long way. He had admitted that they were to be neighbours.

"It's rather nice and very helpful meeting someone who knows all about my destination," she said, turning again to the window to look out. "You will know my cousins, I expect?" Her expression softened in a happy smile. "I am looking forward tremendously to meeting them, although it's sad that I shall never meet Maria now. She was killed in an accident, wasn't she, just over a year ago?"

For a moment there was silence; a moment which gradually took on the essence of time suspended over some dark abyss of indecision and secrecy. Turning in her seat, she looked at her companion, but his expression was already guarded, the dark eyes telling her nothing.

"That is so," he admitted stiltedly. "It remains a tragedy of which no one wishes to speak."

She was quite sure that he could have told her more of the way in which her cousin had died, but she could not press him for the information. She knew that Maria's death had been a shattering blow to her uncle, and when they had received the news in England her mother had wept for the small baby she had once held in her arms, the only child of Robert's that she had ever seen. He had come with his second wife on that one brief visit to his homeland, when Felicity had been too young to remember him, and then he had gone back to his "Enchanted Islands" to settle down to the life he knew best and loved most.

"It must have been a terrible blow to my uncle," she said unsteadily. "Maria was his eldest child and he was passionately fond of her. In his letters to my mother, he wrote of Maria more than of any of the others. She was spirited, I believe, and very beautiful."

"That is true," he acknowledged slowly, almost reluctantly. "She was the most beautiful creature I have ever seen. All Spanish. There was nothing English about Maria."

"You say 'nothing English' as if that were an advantage!" Felicity objected. "Perhaps you do not like the English?"

"On the contrary!" he protested. "I go often to London on business and I like your countrymen very much. If they have not the spontaneous gaiety of the average Spaniard, that is not to their discredit. Perhaps," he added