Reinventing Emma (11 page)

Authors: Emma Gee

Chapter 18

At the Mercy of Staff

The nurse enters, her vicious bright red mouth sighs loudly before she crouches down out of my sight at the end of my bed.

Where has she gone?

A waft of urine wacks me before I can hold my breath â she's emptying my catheter or âhandbag' that accompanies me to my twice-daily physiotherapy sessions. “You must drink more fluid if you want us to take this out, Dear,” she warns, holding up the full catheter bag at a great height. Without waiting for a response, she swivels on her heels and exits my room saying, “Just taking a break for a ciggy.”

As I became more awake and aware of my surroundings I found my life depended on and was dominated by hospital staff. In my former life nurses and other health professionals were just part of the team, but now as a patient my relationship with them was quite different. I was helpless, a child, so reliant on their good grace to get through each day. And, as in all cases, there were wonderful staff members and those who were not so kind. Some, without realising it, made me feel quite humiliated in my new role.

In those first weeks I was unable to look after my most basic personal needs, like washing my hair. The long blonde strands I had left on one side were greasy and streaked with dried red blood. The nurses would tie this remaining hair on the top of my head like a fountain. I couldn't wash it till the Frankenstein staples in the other side of my head were removed.

“OK, let's get these staples out,” says the nurse, after parting my remaining hair as if looking for nits.

Was she sure?

These metal clips clamped my head together and, although I hated them, I could wait. Besides I've already endured ten days of not washing what's left of my hair. But she is ready, even if I'm not. She slips on a pair of rubber gloves, grabs a green kidney dish full of instruments and fiercely clamps a pair of giant tweezers.

“Now just sit still and let me get these buggers out,” she instructs, through clenched teeth.

Sit still? Even if I wanted to squirm free, I couldn't!

I try to close my eyes.

“Gawd I've had an awful morning today. I woke with a horrendous headache and haven't felt right all morning â think I need another coffee,” she says, plucking the metal clips from my skull.

Am I hearing right? She's complaining of a coffee-deprived headache while plucking these things one by one from my head. Plus she is carrying out this procedure when she's tired. Great!

Although I was feeling so traumatised being in this new body, I felt forced by the hospital environment to keep up. For me each event I faced was enough to deal with in a lifetime, but to others it was just part of the daily hospital checklist of tasks. I didn't have time to recover from one activity before being thrown into the next. The staff seemed to think that if I was given time to contemplate the difficulty of what was happening, I would never move forward. So in just one day I had a shower, a physio session, a âfeed' and the staples removed from my head. Visitors were yet to swarm.

To help me swallow, the speech therapist taught my feeders to stroke my neck to encourage the food âdownwards'. Although having someone's finger running down your neck isn't that pleasant, it did reduce the pooling of the awful tasting blobs of mush in my mouth. They had warned me before the op that my taste buds could be damaged. But when I first tried pureed cabbage I knew that they were OK.

Who purees cabbage?

It was just as disgusting as I expected it to be. At least the stroking strategy seemed to minimise the coughing fits and spluttering from choking on the mush. But not all strategies used by my carers were helpful. One nurse thought it would be a novelty to play the âaeroplane game' with my food. Trying to track the flying puree was demeaning. I longed to return to eating normal, solid food again.

Often being young, mute and mentally alert made me the perfect sounding board for nurses' concerns. I'd lie there unable to sleep while their caffeine-loaded bodies dumped their personal sagas into my vulnerable ears. One nurse interpreted my night âbuzzing' for a drink as boredom. She danced my toy lion around my bed, putting on a deep voice. “My name's Simba the lion, I will protect you.” She seemed to think she was entertaining a kid. I lay there thirsty and humiliated.

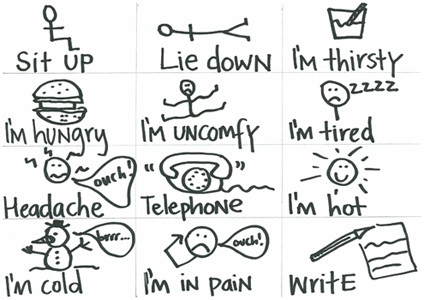

I longed for a means to convey my needs. The images on the communication board given to me by my speech therapist were so tiny I had difficulty seeing them. Also, my ataxia meant that my shaky indecisive fingers would inevitably point to the wrong picture. I'd be bombarded with piles of white hospital blankets when the truth was I was hungry! Eager to lessen my frustration and understand my needs, Bec drew a picture board with large icons. A later version was a letter board, a keyboard printed on paper. I managed to shakily spell out âCAT' and âMUM' but in my mind I needed to spell out something to prove to my therapist that I was all there. I decided on the words ENERGY CONSERVATION. With hindsight I don't know what medication I was on, but it was a health term that I thought would connect us as health professionals. It might prove to her that I still had a sense of humour.

Em's personalised âcommunication board' devised by her sister to ensure she was able to point out her needs with her ataxic fingers and not miss!

(Dalcross Hospital, 2005).

The speech therapist enters and my sister Kate, also an OT, sits on the side of my bed. “Afternoon, Emma. How's your board going?” she asks.

On cue, I start spelling out my chosen words. As I hover over a letter, Kate says it out loud for me, pre-empting the possible word to save me unnecessary pointing. “It's âE' for âEMMA' and âN' for âNellie', it's umm âENER” for ahhhh âENERGY'!” I try to smile.

She's saved me two letters.

Then I continue and Kate looks confused, “There's more, Em?”

I nod. I can't afford to stop. I'm tired but determined. C. O. N. and so on ⦠I get to V and I'm so exhausted I give up.

Suddenly Kate perks up and proudly says, “Conservation ⦠it's Energy Conservation!”

We look at each other in relief. At last, a breakthrough in our communication. I had finally proved that beneath all this physical impairment, I was still here. Kate chuckles at my attempt to show a bit of humour. But the therapist doesn't seem to share Kate's enthusiasm. The 30-minute session is over, and I'm exhausted. Ironically in spelling out that word, I had done the opposite to what I'd intended â all my energy had been exhausted rather than conserved.

I close my eyes and sleep until dinner. I'll prepare for a three-word phrase next, but now I'll rest.

After the stitches were taken out came another milestone â the day they removed the catheter.

What a relief!

But then my continence was tested. If I sensed I needed to do a wee I'd call the nurses and they would assist me to the toilet. Often I'd try so hard but there'd be no action, even when they tried the running water technique. One nurse saw my inability to go as a huge time waster and, with a long, loud huff and a look at her watch, stood about one metre from me, expecting me to go. How could I when she was hovering over me? I was toilet training again.

My greatest toilet humiliation, though, was with using my bowels. I hadn't had a bowel action since waking from my coma. Those advertisements on tellie, marketing laxatives like Nulax, saying that being constipated made you feel “sluggish and irregular” were true. I felt gross, my bloated belly unable to store any more puree. Action was taken. I don't know what they put in my mushy food, but the result was dramaticâ¦

I wake lying in a wet mound of my own faeces. The Coloxyl has worked. I buzzed for help, but am left in this volcanic eruption of my own bodily fluids for what seems like hours. My belly gurgles violently, like the sound of an InSinkErator eating hungrily the remaining kitchen waste. The nurse had shovelled the bitter white substance into my mouth assuring me that it would help “my tummy begin to work more normally”. This explosion has not restored normality.

Finally footsteps come my way and my light goes on. “Oh gosh,” the nurse gasps. She shouts loudly, “The Coloxyl has definitely worked in Bed 21! Can someone help me?” Her voice is now muffled through clenched teeth. “BYO gloves!”