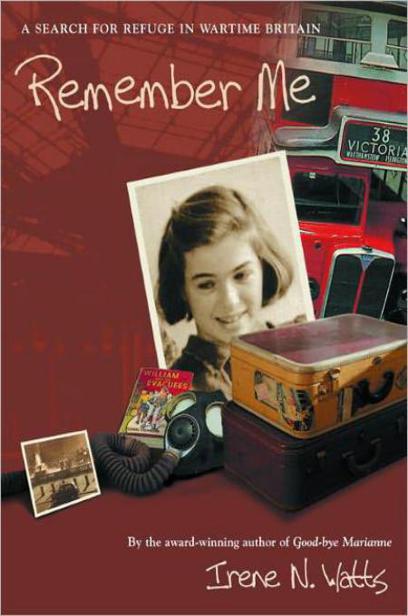

Remember Me

Authors: Irene N. Watts

Also by Irene N. Watts

Good-bye Marianne

As autumn turns into winter in 1938 Berlin, Marianne Kohn’s life begins to crumble. First there was the burning of the neighborhood shops. Then her father, a mild-mannered bookseller, must leave the family and go into hiding. No longer allowed to go to school or even sit in a café, Marianne’s only comfort is her beloved mother. Things are bad, but could they get even worse? Based on true events, this fictional account of hatred and racism speaks volumes about both history and human nature.

Winner of

THE GEOFFREY BILSON AWARD FOR HISTORICAL FICTION FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

and

THE ISAAC FRISCHWASSER MEMORIAL AWARD FOR

YOUNG ADULT FICTION.

Copyright © 2000 by Irene N. Watts

Published in Canada by Tundra Books,

75 Sherbourne Street, Toronto, Ontario

M

5

A

2

P

9

Published in the United States by Tundra Books of Northern New York,

P.O. Box 1030, Plattsburgh, New York 12901

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 00-131205

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher – or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency – is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Watts, Irene N., 1931-

Remember me / by Irene N. Watts.

eISBN: 978-1-77049-051-2

I. Title.

PS

8595.

A

873

R

46 2000 jc813′.54 coo-930415-0

Irene N. Watts gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts in helping her to complete this project.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (

BPIDP

) and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation’s Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

v3.1

For my children and grandchildren

I am grateful to Kathy Lowinger for her encouragement, insight, and in-depth editing; and to Sue Tate, for her meticulous copyediting in “three” languages.

Many thanks to Stephen Walton, Archivist, the Department of Documents, The Imperial War Museum of London, England; to Dorothy Sheridan and Joy Eldridge, Archivists, the Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex Library, Brighton, England, for their invaluable assistance in my research; to Julia Everett, Geoff Shaw, and to the staff of the White Rock Library, White Rock, British Columbia.

Particular thanks to the following individuals who have shared their stories and remembrances of the time: Hilda Farr, Inge Gard, Margot Howell, Judith Keshet, Joseph and Renate Selo, and A.J. Watts.

Thank you to Noel Gay Music Company Ltd. for permission to quote the lines of the chorus of “The Lambeth

Walk”; to Random House UK Limited for permission to quote the text of the telegram from

Swallows and Amazons

by Arthur Ransome (Jonathan Cape, publisher); and to the Literary Trustees of Walter de la Mare, and the Society of Authors as their representative, for permission to quote from the poem “Five Eyes.”

Prologue

“Open up. Gestapo.”

Marianne and her mother collided in the entrance hall. Mrs. Kohn whispered, “Ruth’s letter.” Marianne disappeared.

“Open up.”

The sound of a rifle butt against the door.

“I’m coming.”

Marianne heard her mother open the door. The slap of leather on skin. A stifled gasp. Marianne stood in the doorway of her room. She watched the Gestapo officers, their uniforms as black as the night sky, invade their rooms.

Mrs. Kohn put her finger on her lips. Her face was very white. She waited. Marianne stood without moving, watching her mother. Cupboard doors slammed. Drawers crashed. They heard glass shatter.

Something ripped. Gleaming black boots walked toward Marianne. She edged back into her room, picked up her teddy bear, held him tightly.

The officer patted Marianne’s head. Turned away.

“Let’s go.”

They left. Their boots rang out through the building. A car door shut, the roaring engine disturbing the dawn.

Marianne and her mother did not stir until the only sound they could hear was their own breathing. Mrs. Kohn closed the front door, fastened the chain. She and Marianne held each other for a long time.

“My hair – he touched my hair. I feel sick.”

“We’ll wash it. It’s all over now.”

“What did they want? Were they looking for Vati?”

“Who knows …”

“I hid Ruth’s letter.”

“Where?”

Marianne kicked off her slipper. The folded letter clung to the sole of her foot.

“You were very brave, Marianne. Now we’ll burn it. Come.”

Hand in hand, Marianne and her mother walked into the living room. The room looked as if a tornado had hit. Every single book had been dragged off the shelves, and lay on the floor. All her father’s beautiful

books were scattered, bent, facedown, the pages ripped. His desk was gashed, his chair snapped in two.

Nothing had prepared Marianne for this – not the taunts in the street, nor the smashed Jewish shops, not her mother’s anxious warnings not to draw attention to herself, nor her father’s disappearance – nothing. And yet, why was she surprised? Why hadn’t she expected this? This was what it was like being a Jew in Germany. You couldn’t even close your front door against the Gestapo.… Marianne watched as her mother packed her suitcase.…

“This transport is a rescue operation just for children. A

Kindertransport.

The grown-ups must wait their turn. There are bound to be other opportunities for us to leave.”

“You mean, I have to go by myself? No! Absolutely no. I’d have to be crazy to agree to something like that. I won’t leave you all.”

Mrs. Kohn said, “Marianne, I think you have to. You see, I can’t keep you safe anymore. I don’t know how. Not here in Berlin, not in Düsseldorf, or anyplace else the Nazis are.… One day it may be safe to live here again. For now, we must take this chance for you to escape to a free country.”

“Like animals at the zoo”

T

he guard pushed his way through the corridor. “Next stop – Liverpool Street Station. All change,” he called.

The train slowed to a shuddering halt, expelling two hundred apprehensive, weary children. Steam from the engine misted behind them like morning fog. The children climbed down onto the platform. Not knowing what to do next, they formed an untidy line. Eleven-year-old Marianne took Sophie’s hand. “Come on, we have to wait with the others. Stay close beside me,” she said.

Passersby stared at them curiously. Porters pushing trolleys shouted: “Mind your backs.” A few photographers began taking pictures – “Smile,” they said. A light flashed, or was it winter sunshine coming through the glass domed roof of the station?

“Like animals at the zoo,” Marianne said to the boy standing next to her.

“We’d better smile all the same, make a good impression,” he said.

“Wipe your face, Sophie; it’s got smuts on it from the train,” Marianne told her.

“Are we going to our new families now?” Sophie asked, spitting on her grubby handkerchief and handing it to Marianne, who scrubbed at Sophie’s cheeks.

“Soon.”

Marianne wasn’t ready to think that far ahead. It was only twenty-four hours ago that she’d said good-bye to her mother in Berlin. Today was December 2, 1938, and she was in London – the whole English Channel between her and her parents. The station overwhelmed her with its incomprehensible words and signs.

“A friend of my father’s supposed to be meeting me. I don’t even know what he looks like. Do you know who’s taking you in?” the boy next to her said.

“I don’t know anything. I can’t even remember how I got here. Don’t you feel like we’ve been traveling for a thousand years?” said Marianne.

“A thousand years, the thousand-year Reich, what’s the difference? We’re here, away from all that,” the boy said. “They can’t get us now.”

An identification label spiraled down onto the tracks. A woman wearing a red hat climbed onto a luggage trolley facing them. She tucked a strand of hair behind her ear, and spoke to the children in English, slowly, and in a loud voice, adding to the confusion of

sounds around them. “I am Miss Baxter. I am here to help you. Welcome to London. Follow me, please.”

She climbed down. Nobody moved. Miss Baxter walked slowly along the length of the line, smiling and shaking hands with some of the children. Then she headed up the platform to the front of the line, took a child’s hand, and began to walk. She stopped every few moments, turned and beckoned, to make sure the others were following.

“Come on, Sophie, keep up,” said Marianne. She could hear some women talking about them and shaking their heads, the way mothers do when you’ve been out in the rain without a coat.

“See them poor little refugees.”

“What a shame.”

“Look at that little one. Sweet, isn’t she?”

“More German refugees, I suppose. Surely they could go somewhere else?”

Marianne understood the tone, if not the words. Except for “refugee.”

“We’ll have to try to speak English all the time,” Marianne told Sophie.

“But I don’t know how. I want to go home,” Sophie said.

Marianne was too tired to answer.

A girl dragging her suitcase along the platform said, “This is the worst part, isn’t it? Do hurry up, Bernard, we’ll be last. Vati said, ‘Stay together.’ ” She called to the small boy trailing behind them, then turned to Marianne and said, “That’s my little brother.

Why do boys always dawdle?” They waited for the small boy to catch up.

“Look! A man gave me a penny.” Bernard held out a large round copper coin. “He said, ‘Here you are, son.’ ”

“How do you

know

what he said? You don’t speak English. You’re not supposed to speak to strangers,” his sister scolded.

“I suppose they’re all strangers here and we are too,” said Marianne. “I mean, we don’t know anyone, do we?”