Roaring Boys (9 page)

Authors: Judith Cook

He particularly warns against ‘cross-biting’, a ploy still used centuries later and more recently known as ‘the badger game’. ‘Some unruly mates’, he writes, ‘that place their content in lust, let slip the liberty of their eyes on some painted beauty, let their eyes stray to their unchaste bosoms til their hearts be set on fire.’ They then set about courting the fair one and are almost immediately successful, ‘their love need not wait’, and the young woman either leads the way to the tavern ‘to seal up the match with a bottle of Hippocras, or straight way she takes him to some bad place’. But once the couple have got into bed and are ‘set to it’, there enters ‘a terrible fellow, with side hair and a fearful beard, as though he were one of Polyphemus cut, and he comes frowning in and says “What hast thou to do, base knave, to carry my sister, or my wife?” Or some such . . .’ The accomplice then turns on the woman saying she is no better than a whore, and threatens to call a constable immediately and haul them both before the nearest Justice. ‘The whore that has tears at command, immediately falls a-weeping and cries him mercy.’ The luckless lover, caught in the act, and terrified that his being brought publicly before the Justices will get back to his wife and family, or his lord or his employer, has no option then but to pay up whatever it takes to persuade the ‘husband’ or ‘brother’ to keep quiet. At least in Elizabethan London there was no photographer party to the set-up and at hand to take blackmail pictures.

Greene also gives advice against card-sharpers and how they operate, how cards are marked, games fixed, though swiftly adding ‘yet, gentlemen, when you shall read this book, written faithfully to discover these cozening practices, think I go not about to disprove or disallow the most ancient and honest pastime or recreation of Card Play . . .’, which he could hardly avoid adding for he was a compulsive gambler, another reason why he was always in debt. Overall what his pamphlet shows is how little has changed. It is no surprise to learn, for instance, that the Three Card Trick, or Find the Lady, was as popular a way to part a fool and his money as it is now. He finishes on a warning note, pointing out that his stories of whores, gamesters, picklocks, highway robbers and forgers have been told merely to show how such behaviour leads only to the gallows. Heaven forfend that it might be thought he was writing his pamphlets only to make money.

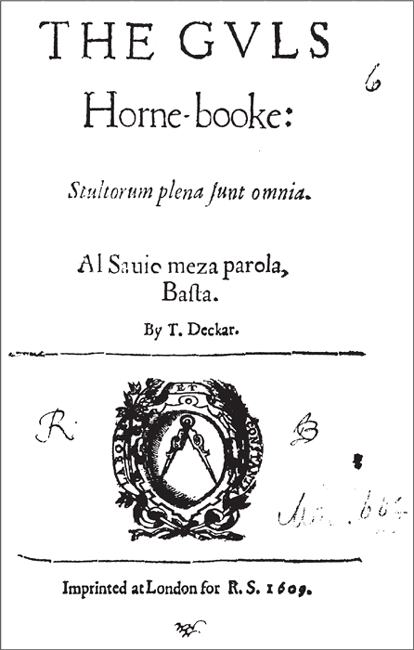

Dekker assumes the role of both narrator and instructor to his young visitor, one inference being that the young man in question is a would-be writer who has just arrived in town. As narrator he addresses both him and us as ‘you’ as we follow them through the day from getting up in the morning to falling into bed at night. We take it that his protégé has arranged to meet Dekker at his lodgings, arriving bright and early and eager for instruction. He is therefore somewhat surprised to find his guide and mentor still in bed. Quick as a flash, Dekker extols the virtues of sleeping in:

Do but consider what an excellent thing is sleep. It is an estimable jewel, a tyrant would give his crown for an hour’s slumber. It cannot be bought. Of so beautiful a shape is it that even when a man lies with an Empress, he cannot be quiet until he leaves her embracements to rest with sleep. So indebted are we to this kinsman of death, that we owe the better tribute of half our lives to him. He is the golden chain that ties health and our bodies together. [However insomniacs must avoid doctors and their noxious potions for even] Derrick the Hangman of Tyburn cannot turn a man off his perch as fast as one of these breeders of purgation.

After chatting on for some time, he finally gets out of bed and, as he reaches for his clothes and gets dressed, gives his advice on what to wear in order to make an impression.

For it is well to try and dress in the fashion. For instance, one’s boots should always be as wide as a wallet and so fringed as to hang down to the ankles. One’s doublet of the showiest stuff you can afford. Never cut your hair or suffer a comb to fasten his teeth there. Let it grow thick and bushy, like a forest or some wilderness. Let not those four-footed creatures that breed in it and are tenants to that crown land, be put to death . . . Long hair will make you dreadful to your enemies, manly to your friends; it blunts the edge of the sword and deadens the thump of the bullet; in winter a warm nightcap, in summer a fan of feathers.

Belatedly they leave Dekker’s lodgings bound for the first tourist attraction and it is clear the young man is amazed at what he sees, the side aisles of the great church being full of stalls, while the middle one is used by those parading up and down to see and be seen, prompting Dekker to remark: ‘Is it not more like a market place than a great house of God?’ He leads his protégé to the stalls of those selling fine cloth, loudly insisting that they are looking for velvet or taffeta for a new doublet. If he is worried about wasting their time, then a good ploy is to ask if there is not something even finer to be had than that they have been shown and, after the stallholder has obliged, ordering several yards of the chosen stuff to be paid for and collected later. Failure to collect it is no problem because the stallholder will soon sell it on. He next turns his attention to those walking in the centre aisle, ‘the Mediterranean’, calling out to all and sundry in a familiar fashion. On someone of note, he advises, ‘you should address him familiarly even though he has never seen you before in his life, shouting out loud that he will know where to find you at two o’clock’.

No visit to St Paul’s is complete without a trip up the Great Tower which costs tuppence:

As you go up you must count all the stairs to the top and, when you reach it, carve your name on the leads, for how else will it be known that you have been here? For there are more names carved there than in Stowe’s Chronicle. [He should take care, though, because the] rails are as rotten as your greatgrandfather [and only recently one, Kit Woodroffe, tried to vault over them] and so fell to his death.

By now, of course, it is time for lunch and the two make for an ordinary without further delay. But even entering such a place should be undertaken in a manner designed to draw attention:

Always give the notion you have arrived by horse. Then push through the press, maintaining a swift but ambling pace, your doublet neat, your rapier and poniard in place and, if you have a friend to whom you might fling your cloak for him to carry, all the better. Let him, if possible, be shabbier than yourself and so be a foil to publish you and your clothes the better. Discourse as loud as you can – no matter to what purpose – if you but make a noise and laugh in fashion, and promise for a while, and avoid quarrelling and maiming any, you shall be much observed.

Remind your friend loudly, for instance, of how often you have been under fire from the enemy, of the

hazardous voyages you took with the great Portuguese Navigator, besides your eight or nine small engagements in Ireland and the Low Countries. Talk often of ‘his Grace’ and how well he regards you and how frequently you dine with the Count of this and that . . . and by all means offer assistance to all and sundry, ask them if they require your good offices at Court? [Or] are there those bowed down and troubled with holding two offices? A vicar with two church livings? You would be only too happy to purchase one.

At this point Dekker suggests his protégé pull a handkerchief out of his pocket, bringing with it a paper which falls to the floor. When it is picked up and handed back to him the response should be:

‘Please, I beg you, do not read it!’ Try, without success to snatch it back. If all press you as to if it is indeed yours, say, ‘faith it is the work of a most learned gentleman and great poet’. This seeming to lay it on another man will be counted either modesty in you, or a sign that you are not ambitious and dare not claim it for fear of its brilliance. If they still wish to hear something, take care you learn by heart some verses of another man’s great work and so repeat them. Though this be against all honesty and conscience, it may very well get you the price of a good dinner.

After lunch then where else but to the playhouse? Not to mention advice on how to ruin the performance of an actor, or the reputation of a dramatist, from one who must have suffered the latter at first hand. It must all be planned beforehand. First, the would-be wrecker must not stand with

the common groundlings and gallery commoners, who buy their sport by the penny. . . . Whether you visit a private or public theatre, arrive late. Do not enter until the trumpet has sounded twice. Announce to all that you will sit on the stage, and then haggle loftily over the cost of your stool. Let no man offer to hinder you from obtaining the title of insolent, overweening, coxcomb. Then push with noise, through the crowds to the stage.

So having reached the stage, you clamber on to it, stand in the middle and:

ask loudly whose play it is. If you know not the author rail against him and so behave yourself as to enforce the author to know you. By sitting on the stage, if a knight you may haply get a mistress; if a mere Fleet Street gentleman, a wife; but assure yourself by your continual residence, the first and principal man in election to begin ‘we three’. By spreading your body on the stage and being a Justice in the examining of plays, you shall put yourself in such authority that the Poet [dramatist] shall not dare present his piece without your approval.

Before the play actually begins it is a good idea to set up a card game with the others who are seated on the stage:

As you play, shout insults at the gaping ragamuffins and then throw the cards down in the middle of the stage, just as the last sound of trumpet rings out, as though you had lost. [Then, as the] quaking Prologue rubs his cheeks for colour and gives the trumpets their cue for him to enter, point out to your acquaintances a lady in a black-and-yellow striped hat, or some such, shouting to us all that you had ordered the very same design for your mistress and that you had it from your tailor but two weeks since and had been assured there was no other like it . . . then, as the Prologue begins his piece again, pick up your stool and creep across the stage to the other side.

After some more chat and fidgeting, as soon as the actors appear:

take from your pocket tobacco, and your pipe and all the stuff belonging to it and make much of filling and lighting it. [Then, as the leading actor strides on to begin his great opening speech] comment loudly on his little legs, or his new hat, or his red beard. Take no notice of those who cry out ‘Away with the fool!’ It shall crown you with the richest commendation to laugh aloud in the midst of the most serious and saddest scenes of the terriblest tragedy and to let that clapper, your tongue, be tossed so high the whole house may ring with it. Lastly you shall disgrace the author of this piece worst, whether it is a comedy, pastoral or tragedy, if you rise with a screwed and discontented face and be gone. No matter whether the play be good or not, the better it is the more you should dislike it. Do not sneak away like a coward, but salute all your gentle acquaintance that are spread out either on the rushes or on the stools behind you, and draw what troop you can from the stage after you. The Poet may well cry out ‘and a pox go with you!’ but care not you for that; there’s no music without frets.

So, with the feeling of a job well done, it is time for the evening meal. There is, however, one problem. By now there is no money to pay for it:

So you will need to find, to pay your reckoning for you, some young man lately come into his inheritance who is in London for the first time; a country gentleman who has brought his wife up to learn the fashions, see the tombs in Westminster, the lions in the Tower or to take physic; or else some farmer who has told his wife back home he has a suit at law and is come to town to pursue his lechery – for all these will have money in their purses and good conscience to spend it.

On entering the tavern, the young hopeful should call all the drawers (the bar staff) by their given names, Jack, Will or Tom, and ask them if they still attend the fencing or dancing school to which he recommended them. ‘Then clip mine hostess firmly around the waist and kiss her heartily, so calling to the Boy “to fetch me my money from the bar”, as if you had left some there, rather than that you owed it. Pretend the reckoning they give you is but an account of your funds. Aim to have the gulls tell each other “here is some grave gallant!”’

Having made his entrance, he should then make a show of visiting the kitchen to see what is being prepared, returning after a little while to recommend this or that dish before joining one of the innocent countrymen at his table and dining in:

as great a state as a churchwarden among his parishioners at Pentecost or Christmas. For your drink, let not your physician confine you to one particular liquor; for as it is required that a gentleman should not always be plodding away at one art, but rather be a general scholar (that is, to have a lick of all sorts of learning, then away), so it is not fitting a man should trouble his head with sucking at one grape, but that he may be able to drink

any

strange drink. . . . [At this stage, Dekker recommends] you should enquire which great gallants are supping in a private room then, whether or not you know them, send them up a bottle of wine saying that it is at your expense. Round off your meal by announcing to the whole room what a gallant fellow you are, how much you spend yearly in the taverns, what a gamester, what custom you bring to the house, in what witty discourse you maintain a table, what gentlewomen or citizens wives you can, at the crook of your finger, have at any time to sup with you – and such like.