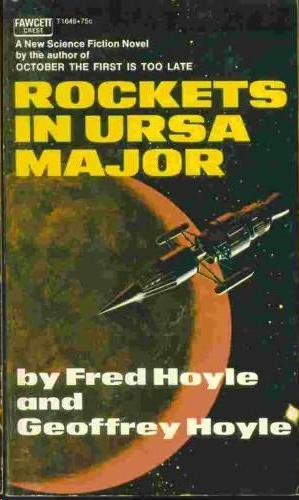

Rockets in Ursa Major

Fred Hoyle and Geoffrey Hoyle

To BARBARA, BERNARD and JOSEPHINE

THE SUN beat mercilessly down on the concrete launching pads at Mildenhall. The DSP 15 stood alone, glinting in the light of high noon. The apron around the ship was a hive of activity as the countdown drew to a close.

Best of luck, Fanshawe,' said John Fielding, the scientific leader of the project. 'When you return I shall have aged much more than you.'

'If your bally refrigerator works properly, Fielding,' replied the ship's Commander. can't quite see myself doing a recce in Ursa Major with a crew of Abominable Snowmen: He turned to his crew. `Right-ho, chaps, off we go. I'll tuck you up in the ice-box when we're on course.'

He held out his hand to Fielding. 'Don't look so worried. We really have absolute faith in the whole machine, so you'd better start looking to that jolly old beacon of yours, and make lots of toddy when you get our re-entry signals. We shall need it: John Fielding smiled and they shook hands.

Tubby Fanshawe moved towards the lift. Suddenly he stopped, and looked hard at a young blushing red-haired - space cadet. 'Ganges! 'Pon my soul, what's the Space Corps coming to? You must have concealed your batting averages.'

`Good luck, Fanshawe. I'm not supposed to be here, but couldn't resist seeing you off.' The young man beamed with pleasure at being recognized in the crowd.

`All the best to you, laddie,' said Fanshawe. 'Don't let the Generals grind you down.' With a last wave to the small crowd that had gathered, he climbed into the lift and was whisked to the crew's cabin at the nose of the ship.

Fifteen minutes later the rocket rose in a cloud of oxygen gas, exhaust flames and concrete dust, slowly tilting on its course for Ursa Major, and a page in history.

I'M not a great one for scientific conferences. This one had been particularly time-wasting, but as the plane left the - ground the boredom of the last few days vanished. I settled back thankfully to think of more important problems. `Hello, Dick,' came an American voice. I turned round to see Dave Swan Vespa, one of the top news reporters for N.B.C. International Television Company.

`How's your research project going?' he inquired. `Too slowly,' I replied grumpily.

`Haven't you fellows got it working yet?' Dave grinned broadly. I grinned back and said nothing.

`See you soon, then.'

He moved off down the gangway. Dave's remark stirred up my irritation at the slow progress on the International radio transmitter. The idea was a good one. Started two years ago by the International Space Exploration Committee, it came after thirty years of almost total inactivity. Loss of exploratory ships in the early 1980s had led to a halt in deep space probes. The only work with space ships nowadays was in the defense of our planet and its environment. Now new life had been injected into space research with the building of this gigantic radio transmitter. Messages would be sent deep into space in the hope that someone somewhere would pick up our signals and transmit an answer back. My part in all this research was to develop a new form of radar valve. The whole program was being almost defeated by insufficient money from disinterested governments. Despite this handicap the scientists kept their research work going as best they could.

When we landed, the usual English weather prevailed, which gave the airport an almost forlorn look in comparison with the bright sunlight of Los Angeles. I went by tube to the Hempstead Heliport, where I was just in time to catch the helicopter taxi to Cambridge.

I climbed in beside the driver. He picked up his punch cards, and selecting the Cambridge one pushed it into the reader. This meant information was fed to the central transport computer which would work out the best possible route, height and speed for the journey. All this information would then be passed to our destination so that, once we were in the air, automatic homing devices would take over and whisk us to our destination without traffic jams or accidents. The police have their own link-up with this computer. It greatly helps in crime detection, but I feel it is an infringement of individual liberty.

A few seconds later a green light appeared on the control panel. The driver fired up the small rocket motors and we lifted into the air, rising vertically until picked up by the homing frequency. The great advantage of the jet against the conventional motor is the smoothness it offers as well as a slight increase in reliability.

It was a clear night, with the stars getting brighter the higher we went. With a light jolt the helicopter stopped rising and moved off in a forward direction.

All was quiet at the Cambridge terminal. My watch showed eleven in the morning. I turned it back eight hours, the time difference between California and London. It was now 3 a.m.

Dawn was starting to come up as I reached the rear gates of St John's College and inserted the old-fashioned key in the lock. The college authorities still hadn't turned over to the new computerized key systems. The metal tumblers clicked away, and I pushed the heavy wrought iron gates open. Locking them behind me, I made my way to my rooms.

When I opened the door, a strong smell of polish and fresh air hit me; my bed maker had obviously had a spring clean while I'd been away. I walked to my desk, just to make sure that my papers were still there, and not in the waste basket, but they were safe. My traveling had made me hungry, so I descended to the kitchenette.

Taking a packet of dehydrated eggs and bacon, I made myself a delicious pan of food. Back m the living-room, I flicked through the television channels until I found a good old film about the Wild West of America in the eighteen-thirties, and settled down before the screen, but the covered wagons and Indians suddenly vanished and the newscaster's face appeared on the screen:

`We interrupt our program with an important announcement from World Space Headquarters. The spaceship DSP 15 has been picked up on its way back to Earth. Older viewers will recall that, almost thirty years ago to the day, this ship was sent out on a mission to the stars of the Ursa Major stream. . . . We have more important news about the DSP 15: it's going to land here in Britain! Stand by for further announcements, and now back to our film.

The film continued, but I was no longer interested. For a moment the news stunned me. Then the phone went. I rushed over to the desk and flicked the switch. A small TV screen on the wall flickered and the picture and sound came.

It was Ganges, a high-ranking officer at the space drome at Mildenhall, a few miles to the east of Cambridge.

`Thank God you're back,' he said, before I could speak. `Have you heard the news?'

`Yes, just. What on earth do you make of it?'

`I daren't think. . . . It's going to land here . . . and soon. . . .' Then Ganges' urgency turned to irony. 'That damned military computer can't find the coding instructions for opening it up.'

`You mean they're mislaid?' I said in disbelief.

`That's about it,' Ganges said candidly. His harassed voice continued, 'Can't get through to Sir John. It's imperative we contact him. He may have the files and we need him here.'

`All right. I'll go now. How long before you expect it?'

`An hour or so . . .' Ganges was about to add to this, but I just nodded as I switched him off.

I hurried out of my rooms and quickly descended the old stone staircase and out into the court. It wasn't far to where Sir John Fielding lived in a lovely old mill-house on the river. He'd resisted all persuasion from the local housing authorities and Senate House committee of the University to move. They wanted the house as a museum.

A sharp walk along the river bank brought me to Sir John's. I trod firmly on the door -mat. A bell rang somewhere inside. Nothing happened, so I pressed urgently again. After a few minutes of standing with mounting impatience in the early morning half-light, I heard the latch click and the door swung in. With immense relief I saw it was Sir John.

`I'm sorry to get you out of bed, Sir John,' I began rather stupidly.

'Why do it?' he" said sleepily.

`The DSP 15 is coming into Mildenhall. . . .

The sleepy eyes opened wide. He was instantly alert. `Come in.' He led me quickly into his study.

`This is quite fantastic, quite fantastic,' said Sir John, looking shaken. 'Coming in!'

`Yes, in about an hour. Ganges rang me up. They're in great trouble. They have no landing instructions. I think Ganges was wondering . .

`What, Dick, what? That I might remember the code? Good God. What sort of memory do they think I've got -- an elephant's? I don't even know where to start looking,' Sir John exploded, getting up and going over to his old filing cabinets. 'Let's get on with it.'

`Try that cabinet there,' he said briskly. 'I'll take this one. Red and green files all marked DSP 15/UM.'

It was nerve-racking trying not to panic. The papers were endless and not in order. Time was so short but I dared not think about it. Sir John was calmly, methodically thumbing through filing drawers, but his face was a grey mask of anxiety. Then unbelievably I found files marked DSP 15/UM. I gave them to Sir John.

`Are these the ones?'

He took them quietly. 'Good, good,' he said, quickly shuffling through them. 'Yes, these are they; not that one; that's injector system, this one's reactor details. Hmm. Interesting. All! here we are, carrier frequencies-pulse lengths 39.37 megacycles. This is it. We'll have the ship down safely and the crew out in a trice.' Sir John beamed happily.

`Come and talk to me while I quickly put some clothes on.'

While he was hurriedly dressing I asked him: 'Why 39.37 megacycles?'

`Number of inches in a meter,' he replied. 'Sort of technical joke, forgotten the point of it now.'

I let it pass. 'What equipment will you need?'

`Nothing unusual. Amplitude modulation, frequency modulation, pulsing and so forth, all straight forward stuff.'

He finished dressing and was off downstairs at a speed Which astonished me. When I reached the hall he was nowhere to be seen, but noises led me to the kitchen. He had a Thermos flask ready, a kettle about to boil and was stirring an amber fluid with sugar in a glass jug. Nearby was a sliced lemon.

`What on earth is that?' I asked.

`Hot toddy,' he twinkled.

'ALL ready,' he said, filling the Thermos.

Why is it coming into Mildenhall?' I asked, tightly holding on to the bundles of files.

'Oh, it's a long story. The ships fly on automatic pilot along a radio beam sent out from Earth. They have to, because the crew is all tucked away in the deep freeze containers to prevent serious ageing during long journeys.'

We moved out of the house. 'Well, when the ships didn't come back,' Sir John continued, 'and we'd completely lost contact with them, some people at headquarters thought there was little point in continuing the radio beams. The British representative fortunately didn't agree, and there was an argument about it. The result was that we here in Britain were given the job of maintaining the beams. Everyone else said it was a hopeless task, but it doesn't look that way now.'

I nodded, remembering the special building at Mildenhall for the beams. I'd done some work there when I was a student and had been told about them.

We walked on to the patio where a small helicopter stood, given to Sir John by one of the large aviation companies.

'Do you mind driving? I want to look at these,' Sir John said. He became deeply engrossed in the contents of one of the files as we took off.

On the outskirts of Cambridge there were a couple of police patrol helicopters. As we approached them our air speed began to reduce.

`What's wrong?' my companion asked, looking up from his work.

The police had obviously been told to stop us as they were indicating that I should take the helicopter down to the ground.

`What do you want?' shouted Sir John from his side of the helicopter. The police went on signaling us to descend.

`We've no option,' I said, taking the helicopter down. `Damned idiots. We're in a hurry.' Sir John was beginning to get annoyed.

Down on the ground the police turned on powerful arc lights.

`All right, gentlemen. Why are you going to Mildenhall?' said one of the men in a challenging voice, leaning in through my side.

`They need me,' said Sir John crossly. `And who might you be?" said the officer.

Other books

Rainbow's End by Katie Flynn

Arcane II by Nathan Shumate (Editor)

Seraphina by Rachel Hartman

Farthest House by Margaret Lukas

Harald by David Friedman

Rose West: The Making of a Monster by Woodrow, Jane Carter

Dirt Bomb by Fleur Beale

The Detachment by Barry Eisler

Light A Penny Candle by Maeve Binchy