Romantic Screenplays 101 (10 page)

Read Romantic Screenplays 101 Online

Authors: Sally J. Walker

Tags: #Reference, #Writing; Research & Publishing Guides, #Writing, #Romance, #Writing Skills, #Nonfiction

Finally, in the

After-Glow

stage, the characters relive the choreography, demonstrating wonder, fear, the shiver of emotion, the anticipation of how this will affect the future and, thus, the story. (CHASING LIBERTY)

The fine art of choreographing the essence of kissing in a screenplay can create incredible motivation for the chemistry between two actors. They must see the sizzle on the page that they can ignite into a memorable, iconic love scene of innuendo, not intercourse. Hot on-screen kissing and titillation of the camera’s perception can infer consummation. Bottom line: Your careful, succinct description and purposeful placement should enhance both the characters’ and audience’s experience!

PAY ATTENTION

Now that you have all these body language tools, try this exercise: Rent your favorite movie. Turn off the volume and describe the major story elements and character emotions you see delivered through body language, especially the kissing and love scenes.

Remember, you want to write movies, not talkies. The only way to do that is to consider what dialogue is absolutely vital and what dialogue can be delivered instead through body language. Know your characters well enough to use their body language to deliver their vital emotions visually, but never to the point of micro-choreography. Play around with the juxtaposition of Primary Affect facial expressions and the character’s actual body language. In DANCES WITH WOLVES, when Dunbar went to the river seeking Stands-with-a-Fist, her words said one thing, but her reaching for and kissing him said what he wanted to hear.

COORDINATING SIGNALING AND HOWARD’S 12-STEPS

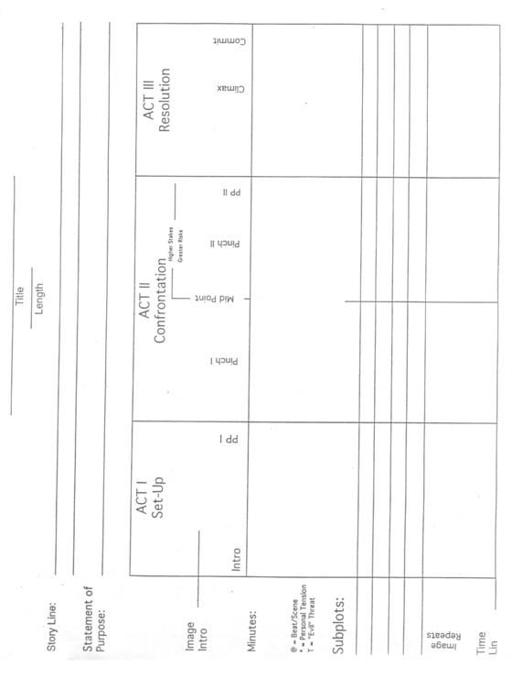

Though the assumption is that any screenwriter reading this book is familiar with the structure of a screenplay, now is the time to review the use of the Paradigm Form and the Definitions of its parts. You will do an overlay of the steps of a romance onto this basic framework.

DEFINITIONS for accompanying PARADIGM:

PARADIGM: A model, pattern, or conceptual scheme of a screenplay / plot line, as explained by Syd Field.

SCREENPLAY: A linear story told in pictures, ranging in length from 90 to 144 pages (each page equal to one minute of screen-time) with current spec length expected to be 100 pages, arranged in three Acts, with an approximate length division of Act I 1/4, Act II 1/2, and Act III 1/4. The writer may originate the script, however, the ultimate product is a revised and refined collaborative effort dependent on performance, production, and technical staff. (A novel is between writer-editor-reader, long, complex with multiple subplots, exposition and internalization

not

present in a Screenplay).

TITLE: Announcement of the story’s content, impact, or image, a succinct and memorable audience grabber. Title is the hook that must be powerfully intriguing but not on-the-nose.

STORY LINE / LOG LINE: One line statement (25 words or less) of what the story is about, a simplified attention-getter that will attract viewers. It must be unique to this story, this Protagonist, delivering dominant character trait and job role in the story, the change or challenge faced and the jeopardy or powerful obstacle the Protagonist must overcome.

STATEMENT OF PURPOSE: The intellectual point or moral of the story, frequently the lesson learned by the characters and demonstrated in the action experienced by the characters.

BACKSTORY: The history of the characters and events preceding this story, creating the situation and / or motivating the characters that will be implied or used as droplet flavoring.

ACT I: Approximately 1/4 of the script, THE SET-UP where the audience is introduced to characters and their problems. The audience begins to ask questions they want answered for the characters. Act ends when an event happens that disrupts life and forces everyone to deal with situations they would rather avoid and the Protagonist is forced into a New Life or way of living.

IMAGE INTRO: Audience’s first sensual experience of the story which establishes mood and expectation. It can set scene, introduce character, create immediate tension, but it must be visually sensational. It should reflect the theme / purpose of the story and can act as a bookend or quotation mark to the story that follows.

INTRODUCTION: First ten pages / minutes when audience experiences the 5W’s of 1) Who the story is about, 2) Where the story is happening, 3) When the story is happening, 4) What events are happening in the life of the characters, and 5) Why these events are disturbing / motivational to the characters. In these ten minutes the audience will decide if they like the story and care about the characters. (Not a Prologue in a novel, but Chapter One)

INCITING INCIDENT: Event happening at 10-17 pg / min which causes Plot Point I. (About Chapter Three of novel)

PLOT POINT I: The event approximately at 23-25 pg / min which totally disrupts the characters’ lives and forces them to deal with situations they would rather avoid, told in approximately 3-5 pages of action and ends Act I. (Chapter Five-Six of a novel)

ACT II: Approximately 1/2 of the script, THE CONFRONTATION where events, choices, and reactions become increasingly more difficult. The audience questions become more intense with the rising tension of the story’s action. Subplots contribute the complications the linear story must deal with and depict character motivation at PINCHES I and II. Herein, the Protagonist is initially learning about / reacting to the new world. Between 48-52 pg / min, an emotional MID-POINT epiphany, an intellectual “Aha,” divides Act II and from that point on the characters are more focused but under greater stress, driven to CAUSE events / consequences. ACT II ends with a vividly dramatic event which forces the characters to take the ultimate action.

PINCHES: Subplot events which depict character motivation / insight and affect the story line. PINCH I occurs approximately 1/4 into ACT II or approximately 35-37 pg / min and is a glimpse of Protagonist’s greatest fear / greatest weakness and PINCH II is a tense highlight approximately 3/4 through ACT II at about 65-67 pg / min that depicts acknowledgement / sense of confidence / impending reward for the Protagonist.

PLOT POINT II: The event at approximately 72-77 pg / min which attacks the Protagonist’s sense of well-being, backs that person into a corner, and forces a decision to take control by confronting the threat and performing the ultimate action that will resolve the situation. It is the Antagonist’s greatest moment when victory / satisfaction is at hand because the Protagonist is beaten. (In a novel this happens approximately at 75-80% point of the book’s length.)

ACT III: Approximately 1/4 of the script, THE RESOLUTION where the characters are at their finest hour, whether the negative Antagonist or the positive Protagonist, the STATEMENT OF PURPOSE is defined, and the linear story is satisfactorily concluded. All audience questions are answered, including SUBPLOT complexities. Suspense / tension builds quickly to culminate in the action climax then falls / mellows with character commitment to some purpose.

CLIMAX (GREAT BATTLE): The dramatic highpoint of the storyline where the audience sees forceful characters pushed to their limits and someone conquers the problems and attains their goal. The Protagonist barely wins

or

discovers something greater to achieve and cherish.

COMMITMENT: The concluding scene sequence where the characters commit to some purpose that will carry them forward beyond the end of the story. This is the audience’s “Ah-h-h,” the falling action or release of tension created in the Climax.

AFTER-STORY: The imaginings of the audience of what the characters do after the cinematic story concludes.

SUBPLOTS: The storylines, each with its own agenda, surrounding the linear / main story of a script which are going on simultaneously and have an effect on the main story, frequently involving supporting cast or the elements that pre-existed and will probably continue after this story is concluded. Where a novel may have numerous subplots, a screenplay must be confined to three to four subplots and only depict those vital to the main story movement. The amount of space (Number of words or pages) given to a subplot equates its importance to the main plot.

IMAGE REPEATS: Images, actions, or dialogue that reappear later in the story for emphasis and impact on the memory of the audience. The dramatic arts rely upon this economical tool to create a sense of unity and purpose in depicting this particular series of events in such a condensed form. In a novel it translates into repeat symbols to subtly deliver the same subtext.

TIME LINE: The passage of time in the linear / main story. Screenplays depict the passage of time through dialogue, costume changes, daily routine actions, time of day or season changes, and character or scene aging, as a few examples.

BEAT / SCENE: Screenplays are built in units called scenes, each comprising a BEAT in the action, each with its own beginning, middle and ending and frequently linked together in scene sequences (subplot events going on simultaneously, for example) to depict many facets of the story within a limited time period in the story.

PERSONAL / SEXUAL TENSION: Subtle element of frustration experienced by the main characters which motivates them to seek resolution. A satisfying story is written in ebb-and-flow with a build of tension, a release of goal attainment or confrontation then a slowing or down-time for audience or reader to absorb / appreciate evolution of story and character. Sustained tension (such as a battle scene) that goes on too long will cause impact to be lost. If too brief the importance may be missed or ignored.

THREAT: The negative or evil elements which touch the lives of the characters, intending to thwart achievement of some goal. The dramatic arts utilize this emotional tool to heighten suspense / tension and enhance audience empathy. The intensity of the threat needs to climb as the story progresses with the Protagonist made aware of more to gain or lose by confronting the threat. Threat can be subtle or blatantly violent. It has to reappear at intervals to remind the audience / reader and keep them in their seats / turning pages.

USE OF THE PARADIGM

After you are comfortable with the form, look at the Subplots section. See how the lines go entirely across the story? ONE of these subplots (possibly the first line) should be labeled “Love Story.” Every time either the hero or heroine encounters the other, you will place a

dot

for that scene. When the encounter

heightens

the sexual tension between them, you place a “T” representing the Threat / Sexual Tension the characters visually demonstrate in that scene. Do you see how you can create a visual tool for pacing the evolution of the romance? Too many dots with T’s too close together and you have clumps of scene sequences without forward story movement as a whole. Too many long, blank spaces (while other subplots are being seen) mean you have gone too long without calling the audience’s attention to the romance!

Which of Howard’s Twelve Steps are subtle, quick movements in your story, thus just dots and which Steps are blatant, sensual scenes filled with Sexual Tension of signaling thus a “T ”on your form?

As you think about how you want your romance to unfold and the timing of the couple’s interaction, look at the main points or sign-posts of the linear story. Ascertain that you have paced the relationship scenes and the timing of the story events to align with the paradigm signposts:

1. The life-changing Plot Point I at the end of Act I

2. The New Life of Act II being keyed to the exploration of the new relationship or the questing for the relationship

3. The Mid-Point Epiphany (where awareness and focus changes) as crucial to the relationship exploding into something more powerful

4. The heart-crushing Plot II where failure threatens but motivates the action of Act III

5. The climactic events creating the survival of the male-female unit.

6. And, finally, the Commitment Scene where the two actually become the committed unit facing the future together.

If you find yourself edging toward predictability, ratchet up the stress in the characters because that will also be experienced by the audience. For example: Remember that the build to the Dark Moment has to be mounting tension and risk, mounting jeopardy . . . then the tension becomes even worse until the release-valve of the Climax in Act III. The audience has to be constantly worried about not only the lives of the main characters but the torn-asunder aspect of the relationship. Will the couple survive to become a unit? Never write this in an over-the-top melodramatic manner but focus on the risky events the characters endure. Do not ever describe or choreograph the emotional displays the actors can deduce on their own throughout this process. You are the writer and they are the actors.