Salem Witch Judge (37 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

At one point he addressed his “Courteous Reader,” suggesting again his hope that these words would find their way into print. “I have written these few lines from a detestation of that Sadducean argument, There shall be no weddings in Heaven [because] there shall be no women there. And out of a due regard to my dear parents, my mother Eve, and my immediate mother, whose very valuable company I hope shortly to enjoy, and through the (to me) unaccountable grace of God, recover an opportunity of rendering them the honor due to them according to the invaluable and eternal obligation of the Fifth Commandment,” which is of course, “Honor thy father and thy mother.”

This is far from Governor John Winthrop’s use of that commandment to argue for the banishment and excommunication of his powerful neighbor Anne Hutchinson. In 1637 in the Cambridge meetinghouse that served as the Massachusetts court, Winthrop had interpreted the fifth commandment to mean, “Honor the fathers of the commonwealth,” in order to silence Hutchinson. As he put it to her, “We do not mean to discourse with those of your sex.” And even after Samuel

Sewall composed Talitha Cumi, nearly two hundred years would pass before women in America were granted the right to vote.

Most historians have assumed that Sewall’s essay on gender equality was never published in its entirety. However, in January 1625 Samuel recorded in his ledger that he paid two pounds to Bartholomew Green, his niece’s husband, “for printing and folding 3/2 sheets Talitha Cumi.” No copies of this twenty-four-page octavo remain.

By this time in his long life, of course, most of Samuel’s thoughts were private. His last significant public appearance was on January 2, 1723, when he was called on to address yet another new governor. The previous day the royal governor, Samuel Shute, had returned to England to report to the Privy Council. Now, in the Governor’s Council chamber at the Town House, Deputy Governor William Dummer, a son of Samuel’s mother’s cousin Jeremiah Dummer, the late silversmith, took the oath of office to lead the province in Shute’s absence.

Samuel stood up to speak. He was now the senior member of the council. At seventy he was the only magistrate alive who had served under the old charter. He was not only alive and relatively healthy, but he still enjoyed wide public support. In contrast, Cotton Mather had alienated many, Increase Mather was deathly ill, and Samuel Willard had died. As for Samuel Sewall, he was “the crusty conservative of such recognizable probity that all sides trusted him,” according to the historian Stephen Foster, which made him “irreproachably independent and in a partisan sense nonpolitical.”

Addressing his cousin who was now the acting governor, Samuel followed John Winthrop in referring to New England as a land specially favored by God. “You have this for your encouragement, that the people [here] are a part of the Israel of God, and you may expect to have…the prudence and patience of Moses…. It is evident that our almighty Savior counseled the first planters to remove hither and settle here,” and that “He will never leave nor forsake them nor theirs.” He closed with an epigraph from the Adagia of Erasmus, “Difficilia quae pulchra,” which translates to, “Difficult things are beautiful.”

Samuel took his seat. All the men in the council chamber rose up to applaud him, which he found delightful and embarrassing in roughly equal parts. In his diary he wrote that the Council “expressed a handsome acceptance of what I had said. Laus Deo.”

By 1728, the year he turned seventy-five, Samuel Sewall had outlived eleven of his fourteen children. He had outlived two wives. He had outlived every other member of his college class and many of his friends. Both the Reverends Mather were dead, Increase in 1724 and Cotton on February 28, 1728. As for the nine Salem witch judges, Samuel was the only one left.

In old age Samuel was deeply grateful for his remaining fruits, his children and grandchildren. “There is all my stock,” he had remarked of his sons and daughters to a Dorchester minister in 1698; “I desire your blessing of them.” Writing in 1720 to Sam Jr., who had asked him to put down his early memories, Samuel said, “It pleased God to favor us” in 1677 “with the birth of your brother John Sewall,” their firstborn. “In June 1678 you were born. Your brother lived till the September following, and then died. So that by the undeserved goodness of God your mother and I never were without a child after the second of April 1677.

“And now what shall I render to the Lord for all His benefits?” Samuel asked his son. “The good Lord help me to walk humbly and thankfully with Him all my days, and profit by mercies and by afflictions, that through faith and patience I may also in due time fully

inherit the promises. Let us incessantly pray for each other, that it may be so!”

Samuel’s long public life was coming to a close. In 1728 he resigned as chief justice of the most powerful court in New England, a position he had occupied since 1718. He resigned from the Suffolk County Probate Court, on which he had served since 1715. Including the nine years prior to 1692 that he was a magistrate of the General Court of the colony as well as his thirty-five years on the Superior Court of Judicature, he had served New England as a judge for close to half a century.

His legacy was a concern. He had tried to be fair and wise. Yet he was, and would always be, a Salem witch judge. On April 23, 1720, as he scanned the contemporary historian Daniel Neal’s new two-volume History of New England to 1700, he was shocked to find New England’s “nakedness” there “laid open in the businesses of the Quakers, Anabaptists, witchcraft.” In regard to the latter he flushed to see his own name in the text. “The judges’ names are mentioned [on] page 502” of the second volume, and “my confession” is on page 536. He prayed, “Good and gracious God, be pleased to save New England and me, and my family!”

As for the dependency of old age, Samuel accepted it gracefully. Over the decades he had prayed for his children. Now they prayed for him. On April 3, 1726, after hearing his son preach on Genesis 1:26, Samuel prayed, “I desire with humble thankfulness to bless God who has favored me with such an excellent discourse to begin my 75

th

year, withal delivered by my own son, making him as a parent to his father.”

Repentance was a continuing process. In November 1707, during one of the public battles over the tenure and behavior of Governor Joseph Dudley, Samuel prayed, “Lord, do not depart from me, but pardon my sin; and fly to me in a way of favorable protection!” Seven years later, in Plymouth on court business, he was called to view the body of a “poor Indian” who slipped off a boat to his death. Samuel knew that the man, twenty-six-year-old Samuel Toon, was “not disordered by drink.” He mused, “I, in many respects a greater sinner [than he], am suffered to go well away, when my poor namesake, by an unlucky accident, has a full stop put to his proceedings, and not half as old as I.” He was still repenting in April 1718, when he wrote on the

occasion of the death of his old friend Elisha Hutchinson, “The Lord help me, that as He is anointing me with fresh oil, as to my office, so He would graciously pardon my sin, and furnish me with renewed and augmented ability for the rightful discharge of the trust reposed in me!” Five years later, a December 1723 sermon on Revelation 2:21 prompted seventy-one-year-old Samuel to pray, “Lord, help me to hear and obey the pungent exhortations to repentance, and that the godliness may be and appear in me! I humbly bless You…and earnestly pray that You would pardon my unworthiness…and that You would condescend to know me and be known of me!”

Samuel had many models in preparing for death. Christ was first. The old schoolmaster Ezekiel Cheever was another. Samuel visited Cheever often in August 1707 as the ninety-four-year-old weakened and died. In Cheever’s bedchamber the two men discussed the “afflictions”—human losses and suffering—which, they agreed, were God’s way of testing and improving humanity. Referring to New Englanders’ afflictions, Cheever said to Samuel, “God did by them as a goldsmith” does. “Knock, knock, knock. Knock, knock, knock, to finish the plate. It was to perfect them, not to punish them.”

Even after the dying Cheever no longer recognized his own son Thomas, whose scandalous behavior cost him his pulpit in 1686, he still knew Samuel. The latter reported, “August 13. I go to see [Cheever], went in with his son Thomas…. His son spake to him, and he knew him not. I spake to him, and he bid me speak again. Then he said, ‘Now I know you,’ and speaking cheerily mentioned my name.” Samuel requested Cheever’s blessing for himself and his family.

“You are blessed, and it cannot be reversed,” the dying man prophesied.

At another visit Cheever took Samuel’s hand and begged him to pray with him.

“The last enemy is death,” Samuel reassured him, “and God hath made that a friend, too.” Cheever lifted his bony hand from beneath the bedcovers and “held it up, to signify his assent.” Samuel, who had observed Cheever enjoy a slice of orange, returned later with a dish of marmalade and “a few of the best figs I could get.”

The next morning Cheever was dead. Samuel wrote in his diary this final note on his friend: “Came over to New England 1637, to

Boston…. Labored in that calling [of teaching] skillfully, diligently, constantly, religiously, seventy years. A rare instance of piety, health, strength, serviceableness. The welfare of the Province was much upon his spirit. He abominated periwigs.” For Boston’s old guard, the wig remained a powerful symbol of evil. A few years before, in January 1703, Samuel had copied six pages “transcribed out of the original manuscript of the Reverend Mr. Nicholas Noyes (of Salem),…‘Reasons against wearing of Periwigs made of women’s hair, as the custom now is, deduced from Scripture and reason.’”

Another inspiration in preparing for death was the Reverend John Eliot. At the grave of Eliot’s wife in 1687 the widower had wept at his inability to join her. Years later, on his own deathbed, Eliot’s last words were “Welcome joy!” Eliot had preached, in a sermon recorded by Cotton Mather, that “our employment lies in heaven. In the morning, if we ask, ‘Where am I to be today?’ our souls must answer, ‘In heaven.’ In the evening, if we ask, ‘Where have I been today?’ our souls may answer, ‘In heaven.’ If thou art a believer, thou art no stranger to heaven while thou livest; and when thou diest, heaven will be no strange place to thee; no, thou hast been there a thousand times before.”

Samuel’s health declined. By 1725 he was “a lame fainting soldier.” His “locomotive facility” was “enfeebled.” He had weak hands, back trouble, and “feeble knees.” His upper and lower teeth fell out. He took this as a “warning that I must shortly resign my head.”

“Lord,” he prayed, “help me to do it cheerfully.”

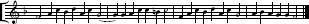

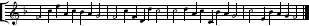

The greatest loss was his ability to sing, which had been a problem for some time. In 1705, when he was only in his early fifties, Samuel had tried to set the Windsor tune for the twentieth verse of Psalm 66 but somehow “fell into” High Dutch. Trying to revert to Windsor, he found himself in “a key much too high.” He felt foolish and asked another man to set the tune, “which he did well,” choosing the Litchfield tune. At church a few years later, in the summer of 1713, he tried to set Low Dutch “and failed. Tried again and fell into the tune of the 119

th

Psalm.” He wondered if he was too old to “line out” the psalm tune so people could hear him and follow. Five years later, also at meeting, Samuel set the York tune, which at the second verse the congregation in the gallery “carried…irresistibly to Saint David’s.”

Bay Psalm Book, 9th Edition, 1698

This melodic shift “discouraged me very much,” Samuel noted. He resigned his post as deacon of the Third Church.

One night in July 1728, after an “extraordinary sickness of flux and vomiting,” he felt it was “high time for me to be favored with some leisure, that I may prepare for the entertainments of another world.”

A month later, though, the seventy-six-year-old retired chief justice went out for a walk after the meeting one Sabbath afternoon. Following a brilliant thundershower, the sun was out. As Samuel strolled through his neighborhood on the Shawmut Peninsula, a “noble” rainbow emerged from a cloud.