Sand rivers (27 page)

On the damp sand just beneath the adina and tamarind grove where we will camp, Kazungu has paused a moment in his digging, as if hypnotized by the upwelling of clear water. Beside him are fresh tracks of both leopard and lion, and as a yellow moon rises in the east to shine through the tamarind's feather branches, a leopard makes its coughing grunt not far downriver. Soon lions are roaring, no more than a mile away. Brian says that because of their poor sense of smell, lions usually depend on vultures to locate carrion for them, and that he'd seen hyena using vultures the same way, going along for a few hundred yards before cocking their heads to locate the spiral of dark birds, then trotting on again. Though he doubts that lion would find the carcass, hyena or leopard might come in this evening, under the big moon.

PETER MATTHIESSEN

That evening I ask Brian if he would ever consider returning to the Selous were he given a free hand to reconstitute it. "You never know," he says, after a long moment. "Don't want to burn all my bridges behind me. But 1 worked for next to nothmg all those years; they can't expect me to do that again. Don't want to wind up on the dole in some little charity hole in the U.K." - and here he looks up at me, genuinely horrified. "Oh God, how I'd hate thatl" he says, and I believe him. There is nothing inauthentic about Brian Nicholson's self-sufficiency and independence, evolved out of hard circumstance very early in his life and reinforced at the age of nineteen when he banished himself to the wilds of Tanganyika. Unlike Rick Bonham (and unlike Philip Nicholson, the only son of a legendary warden of the great Selous) Brian has no romantic heritage in East Africa, or even a strong family to fall back on; neither did he ever have the celebrity enjoyed by the wardens of the great tourist parks, such as Bill Woodley and David Sheldrick and Myles Turner, the ones taken up by the shiny people who made East Africa so fashionable throughout the sixties. Not that he has complained of this, or even mentioned it; he has no self-pity, although here and there one comes upon a hair of bitterness. One day when he lost a filling, 1 told him he'd get no sympathy from me, not after his hard-hearted response to my shattered tooth back there on the Luwegu. This teasing was meant as the only sort of concern he could permit, but Brian failed to smile, saying coolly instead, "Unlike you, 1 expect no sympathy." There was a certain truth in this, but perhaps the remark revealed more truth than he had intended.

"The Selous ought to be set up under its own authority," Brian is saying, "financing itself and administering itself, not vulnerable to people who aren't really interested. That was the trouble down here when I left - lack of real interest. Now Costy Mlay, he was sent down here from Mweka, and he quickly understood the problems and saw the potential. Costy's the exception; he was interested, and he's still interested, even though he is no longer with the Game Department. Costy's very bright, and he's not a politician.

"To lose the Selous now would be such a dreadful waste, and especially when you realize that everything is present that is needed to administer it efficiently, all of the groundwork has already been done! For example, all the road alignment - when 1 was here, we were operating over three thousand miles of dry season tracks. And the placement and grading of the airstrips - that's done, too. They just have to be cleaned up again. There's even the nucleus of a good staff - the old game scouts who still know the country, who could train up a new corps of men, set up patrol posts. That's the first thing 1 would do if I ever came back here, get my old staff together to train up good new people, like some of these young porters we have here now. I'd try to persuade Damien Madogo to come back, and I'd get hold of Alan Rees. Rees was my right-hand man all the way through, he was principal game warden for the Western

.182]

SAND RIVERS

Selous - held the same official rank as 1 did. No story of the Selous would be complete without mentioning Alan; he was a fine hunter and a fine warden, conscientious and patient and very good with his staff, and in addition, he's a first-class naturalist; he just loves being out in the bush, rains and all, and his wife is the same way.

"The senior warden up there in Dar, Fred Lwezaula - he's all right, too. He's doing the best he can, considering the fact that nobody up there in Dar appreciates what they've got down here. There aren't many people in the government who even know where the place is! I don't think it's ever been brought home to them that the Selous is unique. It is not just a big empty part of the ordinary monotonous miombo country that takes up most of southern Tanzania; it's well watered, it's vast, it's almost entirely surrounded by sparsely populated country, it's an ecological unit - or several ecological units, as Alan Rodgers says - and there's nothing like it in East Africa. But the Selous has to be self-supporting if it is going to withstand all the demands for land and timber and the like that are bound to come; we proved it could support itself very easily, and build up the country's foreign reserves as well, and still remain the greatest game area in the world." The WSrden paused for breath, then concluded quietly, "If only for economic reasons, they owe it to the future of their country to see to it that this place doesn't disappear, because it's very precious, and it is unique -1 can't say it too often! There's nothing like it in East Africa!"

Both lion and leopard cough and roar intermittently throughout the night, but at daybreak there are no fresh tracks around the puddle of congealed blood, the pile of half-digested grass stripped from the gut, the sprawl of entrails, the mat-haired head with the thick twisted white tongue. Overhead, the moon is still high in the west, and shimmering green parrots, sweeping like blowing leaves through the river trees, chatter and squeal in the strange moonset of the African sunrise.

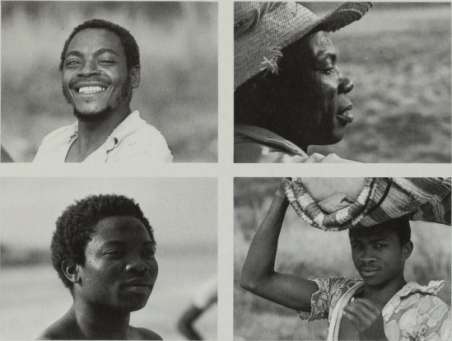

(Top left) Abdallah. (Top light) Goa.

(Bottom left) Davvid Endo Nitu. (Bottom right) Mata.

XI

By the time the buffalo was butchered it was late last night, and the Africans were exhausted; the meat was heaped in a big pile by the kitchen fire to discourage theft by passing carnivores, and this morning, under Goa's direction, Mata and Abdallah are cutting heavy Y-shaped posts and setting them into the ground. The posts will support a rack of strong green saplings, and under the rack a slow fire will be tended that will keep the meat enveloped in thick smoke. "This is a day they will always remember," Brian comments. "Down here in southern Tanzania, they have no livestock at all except a few goats and chickens; the poorer ones get hardly any meat. So this is a unique experience for most of them, perhaps the one time they will ever have it - the day on which they were actually paid to sit around and eat all the meat they could hold. Of course that used to happen with the elephants I had to shoot, but those people weren't paid for it, as these are." He describes how in the old days, traveling light on elephant control, he would camp next to the killed animal in this same way, living exclusively on elephant kidney and sweet tea and rice cooked in advance and packed tight into a sock - a clean sock, mind, he adds, with the trace of a smile.

1 take advantage of a day in camp to go off by myself and look for birds, walking alone up the sand river. By the dead buffalo, a vague cold smell of turning meat is mixed in a repellent way with fleeting sweet whiffs of bush orange, but soon there is only the faint mildew smell of the haze of algaes on the damp sand, which everywhere is cut by the tracks of

PETER MATTHIESSEN

animals; crisscrossing the marks of eland, kongoni, bushbuck, hippo, buffalo, and elephant are myriad patterns of unknown small creatures, and also the round pugs of lion and leopard. Smce I am barefoot, it would be difficult to circle through the bush if something came down into the river bed and cut me off from camp: I listen for the crack of limbs, the buffalo puff, the rhino chuff. Brian had recommended the services of Goa and his .458, but Brian himself has a poor opinion of Goa's marksmanship, and to observe birds with an armed escort —! Anyway, I wanted to get off by myself.

Walking alone is not the same as trudging behind guns; one stays alert. And although this is not the first time on this foot safari that I hear the wind thrash in the borassus palms, the moaning of wild bees, it is perhaps the first time that I listen. Walking upstream, I am shadowed for a while by a violet-crested turaco which moves with red flares of big silent wings from tree to tree, then hurries squirrel-like along the limbs, the better to peer out at me, all the while imagining itself unseen; occasionally it utters a loud hollow laugh that trails off finally into gloomy silence, as if to say, "Man, if you only knew ..." A large patch of blue acanth flowers on the bank is shared by the variable sunbird and the little bee-eater, and when I pause to watch the sunbird, a tropical boubou climbs out of a nearby bush and utters its startling bell notes at close range as its mate duets it from a nearby tree, then unravels the beauty it has just created with a whole run of froggish croaks that cause an ecstatic pumping of its black-and-cream-colored boubou being. Brown-headed parrots and a beautiful green pigeon climb about in a kigelia, which has also attracted a scarlet-chested sunbird. Cinnamon-breasted and golden buntings flit in separate small flocks across the river, and a pair of golden orioles skulks in a bush; ordinarily these shy birds frequent the tree tops. At a rock pool, perhaps a mile upstream, I watch striped kingfishers and a white-breasted cuckoo-shrike, and listen to a bird high in the canopy that I have never heard before and cannot see; its single note is a loud and clear sad paow! Circling it, waiting, listening, I am rewarded at last with the sight of a lifetime species, the pied barbet.

At camp, toward noon, the vultures are already gathering: fifteen griffons have sighted the buffalo carcass and are circling high overhead. But soon they have dispersed again, after swooping in low for a hard look; though nothing threatens vultures, they are wary birds, and too many humans for their liking come and go around our camp less than fifty yards away. There is a lion kill not far downriver, to judge from the resounding noise heard in the night; perhaps the vultures have gone there to clean things up.

In early afternoon, over the river trees, heavy rain clouds loom on the east wind. Then a light rain falls, and the returning griffons, accumulating in dead silence, fill bare limbs back in the forest with dark bird-like growths; at some silent signal, half a hundred come in boldly on

J 861

SAND RIVERS

long glides, feet extended; they strip the buffalo dry and clean within an hour.

By late afternoon the smoked meat is shrunk down to black curled twists of leather. The Africans take turns tending it, and the others sit upright in a circle under the tamarind: the small-faced Mata, and tall Amede, and the small man with the child's wide-eyed face who is called Shamu, and the squealing Abdallah with the squint, and Saidi Kalambo in his big hair and huge blue boxer shorts, and the heavy boy in the red shirt who is called "Davvid" although he is a Mohammedan - "Davvid Endo Nitu," he insists firmly. And Kazungu says, "1 also have a foreign name of 'Stephen', but now I am proud of using my African name."

Only Goa does not join in as the others laugh and tell one another stories. Mzee Goa, as the Ngindo call him, Old IVfan Goa, lies flat out on a piece of canvas, making the most of his day of rest, staring up through the dark green leaves of adina and tamarind at the blue sky. On the tamarind bark over his head, a large agama lizard is pressing up and down in agitation, and not far away, on a broken elbow of a piliostigma, a tree squirrel sits calmly, observing the human camp. Across the sandy soil near my own feet, where I sit on my campaign cot before our tent, a blue-black hornet, hard tail flickering, is dragging a dying spider twice its size toward some dank hole where it can be sealed in with the hornet's eggs.

At dark, the Africans move up close to the kitchen fire, which dances and flickers on the naked skin of dark chests and arms; behind them rises a stand of tall pale grass, higher than their heads, and beside them, on a bed of adina fronds, lies the big pile of dried meat. In more places than one, I think, along the northern borders of the Game Reserve, groups of young Africans such as these must be smoking their poached meat around bush fires very much like this one.

Since his Swahili is excellent and since he enjoys the jokes as much as they do, Brian teases the Africans a lot, and the younger ones joke back at him, as much for their own amusement as for his. Like Kazungu, they are good-natured, never impertinent, there is no air of aggression in their merriment. Yet I notice that Goa, though he laughs sometimes at Bwana Niki's jokes, never volunteers a sally of his own; his is the last of the colonial generation. And the Warden retains the colonial manner with the Africans, giving orders in short and peremptory tones. Except in calling out a name - Kazungu! Goa! (he doesn't know the porters' names - they are all "Bwana") - he never raises his voice; intentionally or otherwise, he usually speaks in such low tones that Kazungu or Goa must come up very close to hear him, seating themselves on the ground before his feet. On the other hand - unlike lonides - he is never abusive or sarcastic, never shows anger even when exasperated, and takes the time to chat with them and make them laugh, though he is embarrassed when I ask him to translate one of the jokes. "Got to keep them simple,