Sand rivers (31 page)

Brian recalls that one of his old hunting rifles had gone to an assistant warden named Johnnie Hornstead, "one of the most generous fellas you would ever meet, and a fine mechanic, too. Old Johnnie was a hell of a mess - great big stout fellow with a big beard, used to go around barefoot all the time. One time there was someone out here, taping a television show, and this TV man said, 'Well, Mr. Hornstead, you must have a lot of time on your hands out here in the bush, may I ask what you do in your spare time?' 'Just mess around,' Johnnie informed him. 'Well, that's very interesting, Mr. Hornstead, but would you mind amplifying that a little? Can you tell us what it means to mess around?' 'Why, certainly,' says Johnnie, 'what 1 do, you see, what I do is, well, I just bugger about!' " Brian whooped with laughter at this memory of old Johnnie, shaking his head. "One day when Johnnie was drunk, he was just sitting there sprawled out, barefoot as usual, a lot of food dribbled down on to his beard, and his drink, too, and the hair on his head all standing up and filthy dirty, and all upset about something or other that I'd said to him on the subject of evolution. And finally he opens up one bleary eye, belching, you know, and he says, 'I don't care if you are my superior, I don't care if you give me the sack for it, I'm going to tell you something, Nicholson — you're socially unacceptable!' " And telling this story, Brian laughs so hard that tears fall from his eyes, and we set each other off, making such a noise that even the Africans stop talking, and in that instant I realize that for better or for worse this socially unacceptable man and I have become friends.

When we stop laughing, we are quiet for a while, listening to the passing of the river. Asked if he thinks our foot safari has been worth while, he nods, saying, "Frankly, Peter, I've enjoyed your company." I have certainly enjoyed his, and say so; I am pleased that both of us can acknowledge this without embarrassment, however anxious we might be

SAND RIVERS

to change the subject as rapidly as possible. "I think this is the prettiest place we've made camp yet," Brian says finally, looking out over the gold-red of the river. "You know, 1 reckon I'm one of the very last people left who's done the real old African foot safari, staying out sometimes for months on end. Trekking with porters through remote, wild, wild bush like this, that hasn't changed a bit in three hundred years - that's not done in Africa any more. In Kenya, people just jump into their Land Rovers and minibuses and combis and away they go, but there really isn't any place left to go to. I saw the last of it up there twenty or thirty years ago, and the Selous is the last of it down here, make no mistake. That's why Rick Bonham is so excited. He's too young to have seen how Kenya was; this is the first time in his life that he's had a look at the real Africa. Wants to move right down here, set up a safari camp. Philip, too," he said. "When I was his age, I was already down here on elephant control, and of course he wants to do what 1 did, and he can't; for one thing, Philip, I keep telling him, you're the wrong color. And for a second thing, you can't be me." No more, I thought later, than Brian Nicholson could be C. }. P. lonides, or than lonides could be Frederick Courtenay Selous. Yet, different though they were, there was a certain continuity between these three unsocial animals, who had strayed out of the herd existence into a hunter's life that, as someone has written, was "lonely, poor, and great."

As he sits there barefoot in his shuka, freshly washed and his hair combed, and fit again after a fortnight in the bush, I have a glimpse of the young Bwana Kijana, come down to the Tanganyika Territories to join the Game Department on elephant control; in the strange half-light of sunset, the lines gone from his face and the gaze softened, he appears much as lonides must have first seen him, as he must have appeared to the pretty Australian girl named Melva Peal, now sitting by the mess tent back at Mkangira, smoking her cigarettes and drinking her tea, and gazing with mild bafflement at the darkening river, winding down across that part of Africa where she has spent most of her life.

Over Brian's shoulder 1 watch Goa; he has gone down to wash, and now sits on his heels by the river's gleam like a driftwood stump. Each evening Goa comes to receive the instructions for the next day from Bwana Niki, and now he approaches and hunches down at a little distance, a mute, dark silhouette on the river bluff. Brian has not noticed him, but when I point, says, "Goa."

"This man here was always interested in the animals," Brian murmurs, as Goa comes and sits down on the ground nearby. "He really cares." In these days on foot safari Brian has spoken with affection and respect not only of Goa but of many Africans he has known and worked with in the bush, granting them status as companions, as real people he could like and trust. When 1 mention this, he frowns. "If you find someone you can work with, out in the bush," he says, "someone you can trust, you're bound to become friends."

PETER MATTHIESSEN

In recent years, Goa Mwakangaru has married a Taita woman sent down to him hy their famiHes, and he has two children. Now he wishes to return to Kenya, although he knows that if he does so there is almost no chance the Tanzanian authorities will send him his Game Department pension. Squatting on his heels near Bwana Niki, as content as ourselves to gaze out on the river, Goa says quietly, "All the good work that we did here in the old days is being ruined. There is nothing for me here in the Selous. I am discouraged, and I would like to return to my own people in the Taita Hills."

During the night, hyenas draw near to vent their desolate opinions, and toward daybreak the lions are resounding. "Never heard them at all," the Warden grumps, sipping his tea in the gray-pink light of the dawn sky; he has slept badly on the narrow camp cots that in recent years have replaced the sturdy safari cots of other days. "Don't like to miss the lions in the night. Never get sick of that sound, no matter how often I hear it."

In the red sunrise, a pair of pied kingfishers cross the path of light on the shallow river to the palm fronds overhead, and mate in a brief flurry in the sun's rays. With the light, the ground hornbills are still, and doves and thrushes rush to fill the silence.

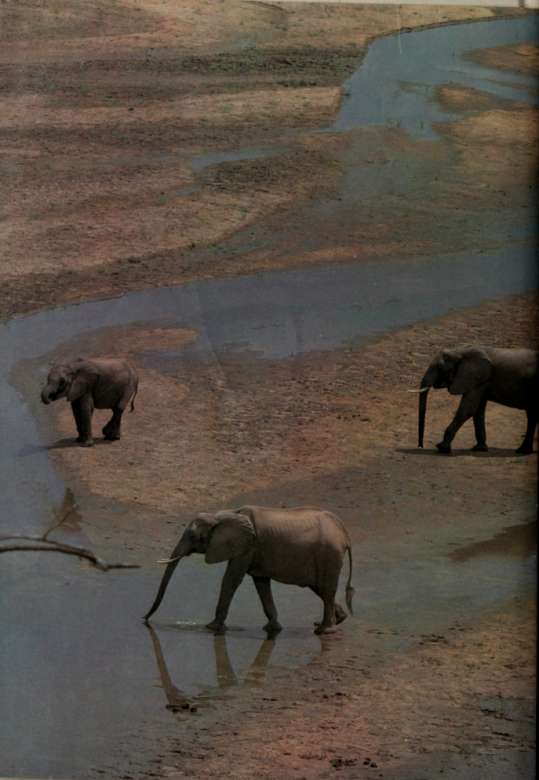

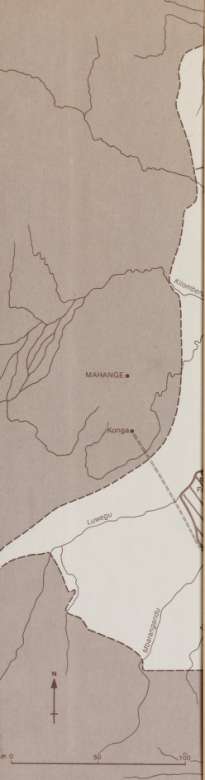

A cool wind out of the south; we head downstream. A herd of impala, the emblematic antelope of Africa, springs away over the green savanna, and as we pass, the great milky-lidded eagle owl eases out of a thick kigelia and flops softly a short distance to another tree, pursued by the harsh racket of a roller. Already tending north-northwest toward its confluence with the Luwegu, the river unwinds around broad sand bars and rock bends, and wherever it winds away toward the east, the man called Goa cuts across the bends, following the river plains, the hills, the open woods, and descending once again to the westward river.

\210]

NOTES

chapter I

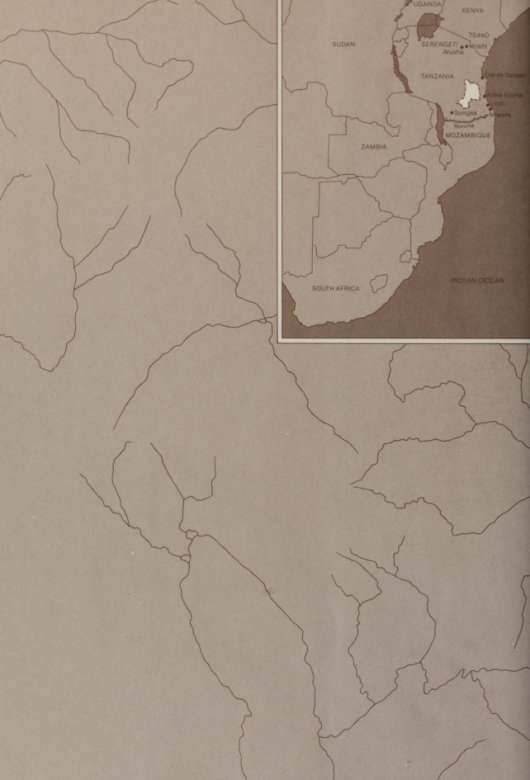

1. And the second largest in the world, after the Wood Buffalo Park in northern Alberta, which can claim scarcely twenty species of large mammals, as opposed to thirty-six in the Selous.

2. Formerly the Queen Elizabeth and the Murchison Falls National Parks.

3. See New York Times, 18 August 1979.

4. Conversation with Dr. Thomas Struhsaker, New York Zoological Society, 16 October 1979. See also Karl Van Orsdol, 'Slaughter of the Innocents', Animal Kingdom, Dec. - Jan. 1979.

Chapter II -*•

1. Conversation with W. A. Rodgers, August 1979.

2. Fielge Kjekhus, Ecology Control and Economic Development in East African History, London: Heinemann, 1977.

3. Margaret Lane,Li/e with lonides, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1963.

4. W. A. Rodgers, 'The Sleeping Wilderness', Africana.

5. Alan Wykes, Snake Man, London: Fiamish Hamilton, 1964.

Chapter III

1. Brian D. Nicholson, 'The African Elephant', African Wildlife, Vol. 8, Part IV, pp. 313-22 (1954).

2. Conversation with Dr. Thomas Struhsaker, 16 October 1979.

3. Conversation with Dr. David Western, October 1979.

Chapter IV 1. At the Mweka College of Wildlife Management, at Moshi.

Chapter VII 1. Nicholson, 'The African Elephant'.

Chapter IX

1. Wykes, Snake Man.

2. See R. M. Bell, 'The Maji-Maji Rebellion in Liwale District', Tanganyika Notes and Records, 1950.

3. K. Weule, 'Native Life in East Africa', London, 1909, quoted in Kjekshus, Ecology Control and Economic Development in East African History.

4. J. P. Moffett, Handbook of Tanganyika, 1958.

Peter Matthiessen'S many works on natural history and the exploration of wild places include The Tree Where Man Was Bom (with Eliot Porter), The Cloud Forest, and the classic Wildlife in America. His most recent book, The Snow Leopard, received the National Book Award for nonfiction in 1978.

Hugo van Lawick is widely known for his photography, particularly of African wildlife. Among his previous books are So7o.' The Story of an African Wild Dog and Savage Paradise.

^^''''1!!'%

THE VIKING PRESS

625 Madison Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10022

Printed in U.SA.

ISBN 0-670-61696-6