Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (37 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

BOOK: Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women

6.23Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In 1897, while traveling in London, she had a reunion with her old pupil King Chulalongkorn. It was an affectionate meeting, the king expressing his thanks in person, but he also took her to task for what she wrote about his father. Her granddaughter Avis Fyshe wrote that the king “expressed sorrow that she had pictured his father as a ‘wicked old man’ in her books. He said, ‘You made all the world laugh at him, Mem. Why did you do it?’ ‘Because I had to write the truth,’ was her answer.”

Anna passed away in 1913 at the age of eighty-three, after spending her final three years bedridden after a stroke. The story of Anna Leonowens and the King of Siam might have been forgotten if it hadn’t been for an American missionary named Margaret Landon, who discovered Anna’s books while living in Thailand. Armed with two hundred pages of a biography by Avis Fyshe, along with letters and other documents, Landon filtered Anna’s story through her own perceptions of Thailand. Margaret Landon’s book was published in 1944 and became an immediate success, selling over a million copies and being translated into twenty languages. It was later adapted into a movie,

Anna and the King

, as well as the hit Broadway musical

The King and I

.

Anna and the King

, as well as the hit Broadway musical

The King and I

.

Anna’s story is remarkable in that she was able to successfully reinvent herself and live an independent life in an era when women had very little personal freedom. It took extraordinary courage for her to leave a life that she was familiar with to live and work in a strange country with only her child for company. She had a frontrow seat in Siam in the decades when the ruler was trying to bring his kingdom into the modern, Western world while maintaining its independence and traditions. She was not afraid to stand up for her rights and for the rights of those she felt were oppressed. Her writings captured the imagination of the West and created interest in Siam. But as one of the first westerners to write about the country, Anna is now remembered for having created an enduring although largely inaccurate portrait of Siam in the nineteenth century.

We people of the west can always conquer, but we can never hold Asia—that seemed to me to be the legend written across the landscape.

—GERTRUDE BELL

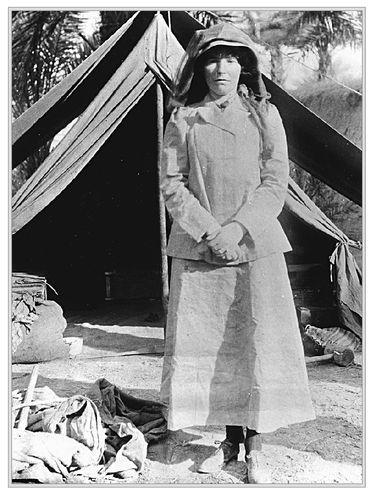

They called her “the Desert Queen,” but that title scarcely begins to encompass the life of Gertrude Bell or her accomplishments. Leaving her comfortable world behind, she explored, mapped, and excavated the Middle East. At one time, she was considered the most powerful woman in the British Empire. Along with T. E. Lawrence, she not only had a role in the Arab revolt against the Turks during World War I but also helped to shape the modern state of Iraq. Today she is best remembered as one of the foremost chroniclers of British imperialism in the Middle East.

A tall, imposing redhead with piercing green eyes, Gertrude Bell was born in 1868 into a life of privilege and ease. From birth it was clear that she possessed the same intellect, energy, drive, and determination that characterized all the Bells. Smart as a whip, she convinced her parents of the wisdom of further education, enrolling at Lady Margaret Hall, one of only two women’s colleges at Oxford.

Gertrude thrived at Oxford although she chafed at the restrictions on women, including that they be chaperoned when they left campus. She also had to deal with the misogyny of the male students and professors. One professor required the female students to sit with their backs to him during class. She was supremely self-confident from the start and wasn’t afraid to debate her professors. With her boundless energy, Gertrude graduated with a first-class degree in modern history in two years, the first woman to do so. Her achievement landed her in the

Times

of London. It would not be the last time that Gertrude’s accomplishments made her newsworthy.

Times

of London. It would not be the last time that Gertrude’s accomplishments made her newsworthy.

Despite her advanced education, Gertrude was still expected to make her debut in society, marry well, and raise children. At the age of twenty-one, she was already three years older than the rest of the debutantes. She spent several months under the guidance of her aunt and uncle in Bucharest, polishing her rough edges, turning her from bluestocking into ingénue. A presentation at court and a formal party announced that she was in the market for a husband. In London she made the expected rounds of parties and balls, where she smiled and laughed, but again she chafed against the rules that required a chaperone to attend an exhibition or even to go shopping.

But as much fun as Gertrude was having, it was a difficult time for her. Frankly, most of the young men she met bored her to tears. They were nice enough but none of them were her intellectual equal or as well traveled, nor could they hold a candle to her adored father. After three years, Gertrude was still on the shelf and facing possible spinsterhood. While she enjoyed the company of men, she refused to change her personality to find a husband, to be docile, silent, and always agreeable.

Just when she had given up looking, she fell in love with both a man and a region. The man was Henry Cadogan, grandson of the Earl of Cadogan, first secretary at the British embassy in Teheran. Ten years older than her twenty-four, he was handsome, well educated, charming, and a brilliant sportsman. They spent their days sightseeing, having picnics, and reading Persian poetry to each other. She fell under his spell and the sensuality of the East that he described. He proposed, but her parents made inquiries and discovered that he had gambling debts. A decision was made for the couple to wait until Henry had sufficient income to be able to support Gertrude. When he died a year later from pneumonia, she was heartbroken.

But her love affair with Persia and the Middle East was just beginning. She continued her studies of the Persian language and published her first two books, one a travelogue called

Persian Pictures

, the other a translation of the poetry of the Sufi poet Hafiz. Restless, she left the drawing rooms of Mayfair behind, to conquer unconquerable mountains, removing her skirt to climb in her underclothes. Always a proper lady, she soon put it back on when she’d reached the top. Traveling around the world, she developed a passion for archeology and languages. By her midthirties, Gertrude was fluent in French, German, and Persian and had a working knowledge of Turkish and Italian.

Persian Pictures

, the other a translation of the poetry of the Sufi poet Hafiz. Restless, she left the drawing rooms of Mayfair behind, to conquer unconquerable mountains, removing her skirt to climb in her underclothes. Always a proper lady, she soon put it back on when she’d reached the top. Traveling around the world, she developed a passion for archeology and languages. By her midthirties, Gertrude was fluent in French, German, and Persian and had a working knowledge of Turkish and Italian.

Falling under the spell of the desert, Getrude studied Arabic and was soon riding sidesaddle, wearing a special divided skirt, alone with a guide, a cook, and two muleteers. Traveling in high style, she brought all the comforts of home with her: crates filled with Wedgwood china, crystal stemware, table linens, tea service, volumes of Shakespeare, a fur coat for cold desert nights, and a canvas tub for long, hot baths. To fool officials who might search her luggage, she kept her pistols tucked in her underwear. A clotheshorse, Gertrude saw no reason not to wear an evening dress just because she was in the desert. Plus, she knew the sheiks would judge her by her possessions and gifts and act accordingly. Gertrude was unafraid to venture into areas that few women, let alone men, had penetrated, including the domain of the Druze, a closed Muslim sect, where she befriended their leader Yahya Bey.

Gertrude had the gift of gab; she could talk to anyone about anything. She talked politics and gossiped with the sheiks, sipping strong Turkish coffee and taking turns with the narghileh, a bubble pipe filled with tobacco, marijuana, or opium. Like her hosts, she ate with her hands, and she never flinched at what was served. With an eye for detail and gossip, she kept meticulous notes in her diary of meetings and conversations, comparing what she’d learned in one place with what she learned in another to see the big picture. Gertrude had been looking for a purpose in her life and she found it in the Middle East. She felt at home in the desert in a way that she never had in the drawing rooms of London. The Arabs excited and stimulated her imagination. There she felt she could make a real contribution. She shared her insider knowledge of the local tribes with the British consulates and embassies, and her opinions and recommendations were taken into account by those in power.

Gertrude crisscrossed the desert through the areas that make up most of present-day Syria, Turkey, and Mesopotamia, covering more than ten thousand miles on the map, traveling either by horseback or camel. She targeted her travels on archeological sites in unmapped territories, hoping to make some undiscovered find. Traveling in 1913 from Damascus to the desert of northern Arabia, the Nejd, where no westerner had traveled for twenty years, she was taken prisoner by the emir’s uncle in Hayyil and held for nine days before she talked her way out with sheer bravado. Publishing her findings in several books, including

The Desert and the Sown

, her observations opened up the Arab deserts to the Western world.

The Desert and the Sown

, her observations opened up the Arab deserts to the Western world.

During World War I, the Admiralty Intelligence Service in Cairo sought assistance from those with knowledge of prewar Arabia. Gertrude’s ability to speak the language and her knowledge of the desert tribes made her uniquely qualified. She became the first woman officer in the history of British intelligence, although her designation as major was only a courtesy title. However, she was made a general staff officer, second grade. In Cairo, she became reacquainted with T. E. Lawrence, whom she had first met on an archeological dig in 1913. Her job was to organize and process data about the Arab tribes: her own, Lawrence’s, and Major David Shakespear’s. The goal was see if the Arabs could be encouraged to join the British against the Turks, who were allied with the Germans in the war.

In 1916, Gertrude was sent to Basra to advise Sir Percy Cox, the chief political officer with the expeditionary force. She wrote reports on the Bedouin tribes and the Sinai peninsula, some of which were collected and produced as an instruction manual for British officers when they arrived in Basra. Her reports were noted as the clearest and most readable official documents that the Arab Bureau ever produced. In March 1917, after the British took Baghdad, Gertrude was given the title “oriental secretary.” Her role was as a facilitator with the various tribes to convince them to support the British administration in the region, to listen to their concerns, and to assure them their rights would be maintained. The tribes trusted her, and called her Khatun, or “Desert Queen,” or Umm al Muminin, “Mother of the Faithful,” after the Prophet’s wife Ayishah.

In 1917, Gertrude was named a Commander of the British Empire but she was not impressed. “I don’t really care a button. It’s rather absurd, and as far as I can see from the lists there doesn’t appear to be much merit in this damn order.” Gertrude wasn’t dazzled by awards. She found it abhorrent that anyone would think that love of title or honors was her motivation.

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Gertrude was asked to conduct an analysis of the situation in Mesopotamia and the options for future leadership of the region that is now Iraq. Gertrude’s report came down on the side of Arab self-determination but her superior, A. T. Wilson, was an old-fashioned colonialist who still believed in the might of the British Empire. In 1921, Gertrude, Lawrence, and Percy Cox were among a select group at a conference in Cairo brought together to find a way to reduce the British presence in the Middle East after the war. Throughout the conference, she worked tirelessly to promote the idea of creating the nation that we now know as Iraq, to be headed by Faisal, the son of Hassan bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, one of the instigators in the Arab revolt against the Turks.

Until her death, Gertrude served on the Iraq British High Commission Advisory Group. She became a confidante of Faisal, helping him to achieve his election as king by introducing him to the tribes in the region and earning herself another nickname, “the Uncrowned Queen of Iraq.” She founded the British School of Archeology in Iraq, as well as the Archeological Museum in Baghdad. But Gertrude soon found that working with the new king was not always easy. He could be secretive, manipulative, and too easily influenced. Her experience with him led her to declare, “You may rely on one thing, I’ll never engage in creating kings again; it’s too great a strain.” But she remained in Iraq, working through illness and rarely taking vacations, worried that the region was still too unstable for her to leave for long.

Other books

The Blonde Theory by Kristin Harmel

The Sanctuary (Playa Luna Beach Romance) by Collins, Sarah

Lessons in SECRET by Crystal Perkins

Of Shadows and Dragons by B. V. Larson

With This Ring by Carla Kelly

Ruth's Bonded (Ruth & Gron Book 1) by V.C. Lancaster

Black Silk by Retha Powers

Bellefleur by Joyce Carol Oates

One Week (HaleStorm) by Staab, Elisabeth

Crazy People: The Crazy for You Stories by Jennifer Crusie