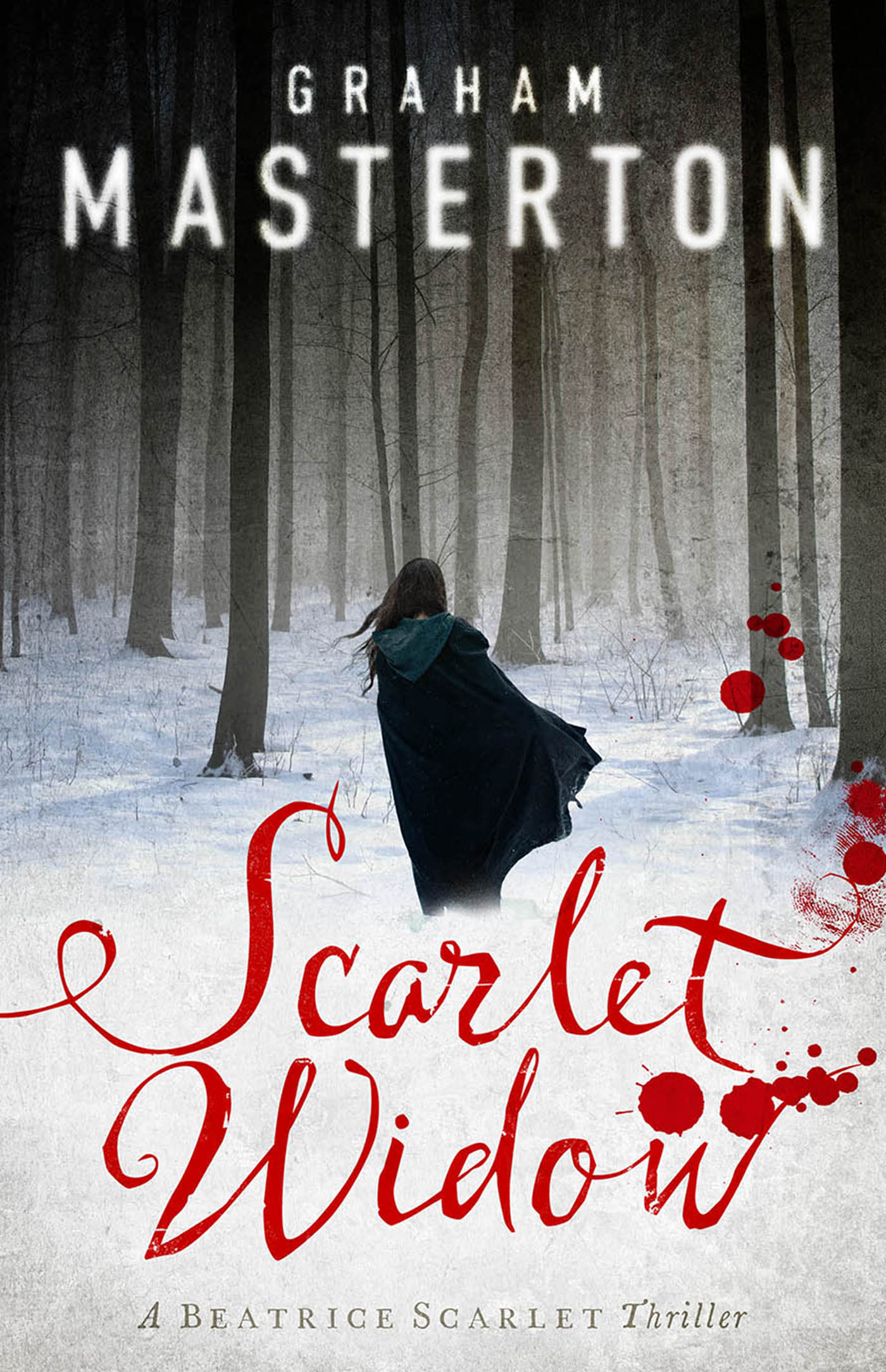

Scarlet Widow

Authors: Graham Masterton

About The Scarlet Widow series

About the Katie Maguire series

For Kinga Kaczanów

who loves science

with love

About The Scarlet Widow series

About the Katie Maguire Series

An Invitation from the Publisher

Early on Easter morning, after a long and painful labour, Beatrice gave birth to a baby girl. When she heard her crying, she felt as if she had rolled away the stone and miraculously come back to life.

‘She’s beautiful,’ said Goody Rust, holding her up for Beatrice to see her. ‘Dark hair, just like yours. But she has her father’s eyes, don’t you think?’

‘Be careful to cut the cord short,’ put in Goody Kettle. ‘We don’t want her to grow up a strumpet!’

Beatrice sat up a little, her curls damp with perspiration and her mouth dry. The early-morning sunshine blurred her vision, so that the crowd of friends and neighbours in her bedchamber seemed like an ever-shifting shadow-theatre. Seven of them had sat around her all through the night, feeding her with groaning cakes and beer and comforting her when the pain had been at its worst. Now they were chattering and laughing and passing the baby around from hand to hand.

Goody Rust sat down on the bed next to Beatrice and plumped up her pillows for her. ‘I’m certain that her life will be a happy one,’ she said, gently. ‘You know what they say, that the tears of grief always water the garden of happiness.’

‘I’ve wrapped up the afterbirth for you,’ said Goody Greene. ‘I’ll take it down to the kitchen so that Mary can dry it for you.’

Beatrice smiled and said, ‘Thank you.’

‘Here, lie back,’ said Goody Rust. ‘I’ll clean off all that hog’s grease for you, and then you can get some sleep.’

‘Let me just hold her before you do,’ said Beatrice. The baby was passed to Goody Rust and Goody Rust laid her in her arms.

The baby’s eyes were closed now, although Beatrice could see her eyes darting from side to side underneath her eyelids as if she were already dreaming. She touched the tip of her nose with her fingertip and whispered, ‘Who are you, my little one?’

On Christmas morning, on their way back from church, they came across a cherub kneeling in a doorway.

She wore a halo of knobbly ice on her head and on her back a thin frost-rimed blanket had given her white folded wings. Her milky blue eyes were open and her lips were slightly parted as if she were about to start singing.

Beatrice’s father stood looking at her for a long moment, then he reached out and gently touched her shoulder.

‘Frozen solid,’ he said. ‘You carry on home, Bea. I’ll go back and fetch the verger.’

Beatrice hesitated, with the snow falling silently on to her bonnet and cape. She had seen dead children in the street before, but here in this alley that they had taken as a short cut home, this girl made her feel much sadder than most. It was Christmas Day, and the church bells were pealing, and she could hear people laughing and singing as they made their way along Giltspur Street, back to their homes and their firesides and their families.

Not only that, the girl was so pretty, although she was very pale and emaciated, and Beatrice could imagine what a happy life she might have had ahead of her.

‘Go on, Bea,’ her father told her. ‘There’s nothing more anybody can do for her now, except pray.’

That afternoon, over their roasted beef dinner, her father said, ‘I wonder if it would ever be possible to preserve your loved ones when they pass away, exactly as they were when they were alive?’

‘What on earth do you mean, Clement?’ asked Beatrice’s mother, spooning out turnips on to his plate.

‘I mean, like that poor little girl that Bea and I came across this morning. She was only frozen, of course, so her remains won’t last for long. But supposing you could petrify people or turn them into wood? Then you could keep them with you always.’

‘Oh, Clement, what an idea! I couldn’t have a wooden statue of my mother sitting at the table with us! It would give me a fit!’

He smiled and shrugged and said, ‘Yes... yes, you’re probably right. But one could do it with a pet, perhaps. A cat, or a dog. Then your child could play with it

ad infinitum

.’

Beatrice put down her spoon.

‘What’s the matter, Bea?’ her mother asked her. ‘Aren’t you hungry?’

‘I can’t stop thinking about that girl,’ said Beatrice. ‘If only somebody had given her something to eat and a fire to keep her warm.’

‘Bea, you shouldn’t upset yourself. She’s in heaven now, and Jesus will be taking care of her.’

Beatrice said nothing. She didn’t want to contradict her mother. But although she was only twelve years old, and she had never been brought up to think any differently, she couldn’t help wondering if heaven were really real, or if it were just a story that was made up to make us feel better about people we had lost. Perhaps when you froze to death you felt cold for ever after.

‘Come here, Bea,’ said her father, appearing in the kitchen doorway, with the sun behind him. ‘I have something wonderful to show you!’

‘Oh,

please

, Clement!’ her mother protested. ‘Her breakfast is ready!’

‘This won’t take long,’ said her father. His eyes were lit up and he was smiling, the way he always did when one of his experiments worked out well.

‘That’s what you said when you made that so-called volcano,’ her mother retorted. ‘“This won’t take long!” and the poor girl came back two hours later reeking of sulphur as if she had been to hell and back!’

She coughed, as if the very memory of it irritated her throat.

‘Only five minutes this time,’ said her father. ‘I swear it, on my dear mother’s life.’

‘Clement, you know very well that you

detested

your mother, and in any event she passed away years ago.’

But Beatrice settled the argument by pushing back her chair and going across the kitchen to take her father’s hand. ‘What is it, papa? Have you made that lightning?’

‘No, no, Bea. I haven’t quite managed to make that lightning yet. I will, I believe, but this is different! Come and see for yourself.’

Beatrice looked at her mother pleadingly, and after a moment she waved her hand at her and said, ‘Go on, then! But only five minutes because your porridge will grow cold!’

Beatrice and her father went out through the scullery and crossed the small high-walled herb garden hand in hand. The garden was planted in neat triangles with absinthe and fennel and lavender and rosemary and sweet cicely. It was a summer morning, already warm, and the fragrance of the plants was so strong that it made Beatrice sneeze.

‘Bless you!’ said her father. Then, looking down at her and smiling, he said again, much more quietly, ‘Bless you.’

He ushered her into the whitewashed outbuilding at the back of the house. This was where he ground up all the herbs and spices for his customers, and prepared his medicinal mixtures, and where he worked on what he called his ‘mysteries’. It was cool and dark in there because the windows were very small and grimy. Three of the walls were lined with shelves, and every shelf was crowded with flasks and apothecary bottles filled with pink and green and amber liquids, as well as china spice jars labelled ginger, galingol, saffron, pepper, cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg. There was a strong smell in here, too, but unlike the aromatic smell in the herb garden, it was pungent and musky. It always put Beatrice in mind of far-off places where men wore turbans and women wore veils, and everybody flew around on carpets like in the

Arabian Nights

.

‘You will not believe this, Bea, when you see it,’ said her father, guiding her over to the workbench at the end of the room. The surface of the bench was cluttered with pots and pans and candle-holders and all kinds of strangely shaped glass retorts. Right in front was a canoe-shaped copper container, rather like a fish kettle, which was half filled with viscous yellow oil.

Beside this container, Beatrice’s father had spread out a brown cotton cloth, although it was humped up in the middle and there was plainly something hidden underneath it.

‘You remember at Christmas, when we found that poor frozen girl in Bellman’s Alley, and I spoke to you of turning animals into wood, so that a real animal could become a toy?’

Beatrice nodded, her eyes wide. She said nothing, because whatever her father did always surprised her. He had once magnified a drop of water and shone its image on to the wall to show her all the microscopic living creatures that swarmed inside it. Another time, he had made sparks fly from his fingertips, as if he were a wizard. He could make liquids change from green to purple and then back again, and iron filings crawl across a sheet of paper like spiders, and he could snuff out lighted candles without even touching them. He had even made a dead frog jump off his workbench and on to the floor.

He took hold of one corner of the cloth. ‘What you are about to see, Bea, is a scientific marvel that man has sought for centuries to achieve! Even the greatest alchemists of ancient Egypt were unable to fathom how this could be done!’

Beatrice couldn’t help laughing. Her father was normally very sober and undemonstrative, and when it came to talking to his customers his face was unfailingly grave. He was good-looking, in a slightly foxy way, with prematurely grey hair brushed straight back from his forehead and a neatly trimmed moustache and beard. He usually dressed very formally, but this morning he was in his shirt-sleeves, without even a collar.