School of Meanies (2 page)

The Ghost Headmaster

After breakfast the next morning, Tabitha Tumbly and Charlie Vapor wisped me straight to the Ghost Headmaster’s office.

Charlie knocked on the door with his knuckles, doffed his hat—the polite thing to do, no fibbing!—and passed through the wood.

“Let’s leave Charlie to it,” I said, and I tried to wisp out of the window but Tabitha snapped her fingers and the window slammed shut.

The door to the Ghost Headmaster’s office opened, and Charlie was there in the doorway. He looked like he’d seen a ghost.

“Best manners,” Charlie whispered into my ear as Tabitha and I floated into the office. “The Headmaster is in a bad mood.”

“He’s always in a bad mood,” I said.

“Close the door,” the Ghost Headmaster said in his vaporous voice, and the door slammed closed and Tabitha looked at me and winked. “Right,” the Ghost Headmaster said, wisping around, “what’s all this about?”

“Um,” Charlie said, hiding behind his hat.

“Humphrey is a pupil here at Ghost School,” Tabitha said. “At least, he was.”

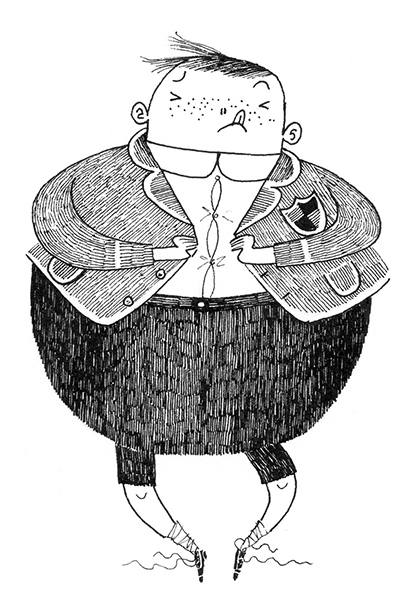

“Ah, the Rotund Rascal,” the Ghost Headmaster said with a smiling mustache. “That’s what the teachers call the boy. Humphrey Bump, the Rotund Rascal.”

“I’m not a rascal,” I said, my voice shaking. “I just bump a lot, for fun.”

“Yes,” the Ghost Headmaster said. “And, thus, expulsion.”

Charlie frowned. “If only Wither were here,” he whispered. “Wither understands all that poetic talk.”

“What the Ghost Headmaster is saying,” Tabitha whispered, “is that the reason poor little Humphrey got expelled is because he bumps.”

“Always bounding about,” the Ghost Headmaster said as he sat in a transparent

ghostly chair. “The boy simply does not fit in. Humphrey Bump is a round peg in a square hole.”

“It’s hardly my fault the hole is the wrong shape!” I yelled, and Charlie elbowed me in the tummy and told me to shush.

“Take, for instance, the brass band incident,” the Ghost Headmaster went on. “I’d arranged for a marching band to parade by the school gates. All went well until Humphrey here bumped the conductor, and the conductor got his head stuck in the tuba and tumbled into the percussion section and bounced off the big bass drum and ended up up-ended in a hedge.”

“Bumping is fun,” I said, and I bumped the Ghost Headmaster, knocking him off his ghostly chair.

“You oaf!” the Ghost Headmaster cried, wisping to his phantom feet. “Get that boy out

of my school at once.”

Plums

That afternoon, I heard the

clack-clack-clack

of the clicky-clacky typewriter, so I peered into the study, and there was Wither typing up his poems, and Agatha dialing a number on the telephone, and Pamela, Charlie, and Tabitha floating by the window.

“Wither,” Charlie said, “leave it to Agatha. By the time the post-phantom delivers the letter to the other ghost school and the ghostly head teacher types a reply, Humphrey will be old enough for college.”

Wither wasn’t typing up his poems as I’d thought. He was typing a letter to another ghost school!

“Don’t be mean,” Wither said as he typed with one bony finger. “The typewritten word carries a certain—”

“Let Wither waste his time if he likes,” Tabitha

said. “Agatha, have you finished dialing that number yet?”

“My hair keeps blowing into my eyes,” Agatha said, “and I dial a wrong digit and have to start all over again.”

Agatha Draft is the sort of ghosty who blows an eerie breeze wherever she floats. She’s also dead posh.

“There!” Agatha said as she finally finished dialing.

“Put this in your mouth,” Pamela said, and she popped a purple plum between Agatha’s lips.

“What is it?” Agatha said, sounding more posh than ever.

“A plum,” Pamela said, “to make your voice plummy.”

“Agatha’s voice is plummy enough as it is,” Charlie said, adjusting his tie.

Tabitha and the other grown-up ghosties gathered around to listen as Agatha talked into the mouthpiece. “We were wondering if you had room for our boy. Humphrey is the name. Humphrey Bump.” Agatha raised an eyebrow at this point and plonked the telephone receiver back into its cradle.

“What happened?” Tabitha asked.

“The rude thing hung up on me,” Agatha said.

Agatha telephoned several other ghost schools, but whenever she mentioned my last name, they hung up.

When Tabitha announced that there were no ghost schools left to call, I bounced through the door and bumped every ghosty in that study—no fibbing!

“Calm down, Humphrey,” Charlie said, straightening his trilby.

“Hooray!” I yelled. “I won’t have to go to Ghost School ever again.”

“I’m afraid Humphrey is right,” Tabitha said. Just as I was about to bounce off to the garden and bump the ghostly gardener into a prickly hedge, Tabitha added, “There is only one thing for it. Humphrey will have to go to Still-Alive School, with the still-alive children.”

Wither tugged the smudged letter from the clicky-clacky typewriter and crumpled it into a ball. “But, Agatha, the still-alive children are meanies.”

“It’s a mean world,” Agatha said, plucking the plum from between her lips. “And it’s even meaner to those who do not possess a proper education.”

Badge, Satchel, and Books

I spent the next few days stuffing my mouth with pies, sausages, pizza, pies, and cake. If I make myself fat, I thought, my uniform won’t fit and I won’t have to go to Still-Alive School.

“Almost done,” Agatha said early on Monday morning. Me and the grown-up ghosties were floating around in the living room, watching her sew a new badge onto my ghostly blazer.

“There,” Agatha said, and she held up the blazer for all to see.

“Where did you find a ghost Still-Alive School badge?” I asked her, licking my lollipop.

“It’s rather a sad tale,” Agatha said, almost in a whisper. “One of the still-alive pupils climbed into the lion cage at the zoo. The lion ate him in one gulp. When he turned into a ghost, Charlie pinched the ghostly badge from his ghostly blazer.”

“I didn’t pinch it,” Charlie said. “I swapped it for a tub of raspberry-ripple I-scream.”

“Fancy being eaten by a lion,” said Pamela Fraidy. “The very thought gives me the shivers.”

“Serves the boy right,” Wither said. “This boy had a nasty habit of bopping felines on the head with a rolled-up comic book. Kittens to begin with, then tabby cats and alley cats—”

“I guess he got greedy,” Agatha said. “Now, try this on.”

“Thank you, Aunty Aggie,” I said. “I can’t wait to start my new school,” I added with a crafty smile.

I slipped my arms into the sleeves, then pulled the blazer at the front, but the buttons wouldn’t reach the buttonholes, not even nearly.

“Humphrey,” Charlie said, wisping out from the lampshade, “you’ve put on weight.”

“What a pity,” I said, tugging the blazer from my arms. “I’ll just have to stay at home and read comic books.”

“You will do no such thing,” Agatha said.

“This explains why he’s been eating so much,” Tabitha said.

“Humphrey, you should be ashamed of yourself.”

“You will have to go to Still-Alive School whether the blazer fits or not,” Agatha said.

“But the still-alive children will laugh at me,” I blubbed. “They’ll call me Small-Blazer and poke me with a stick.”

After breakfast, I found Wither and Tabitha in the hall.

“Humphrey,” Tabitha said, “are you sure you don’t want one of us to float to school with you?”

“No, it’s fine,” I said as I tied my tie. “I know the way.”

“Here’s your satchel,” Wither said, passing me the horrible leather bag. “I’ve packed the complete works of Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and Dickens. Oh, I also included a few of my own writings, typed doubled-spaced on the clicky-clacky typewriter.”

“He’ll never read all that,” Tabitha said.

She opened the front door using her poltergeist powers, and I floated out into the late-summer sun.

The moment Tabitha closed the door, I floated behind the hedge, dragging the phantom satchel. A second later, the door opened with an eerie creak.

“Can you see him?” I heard Tabitha ask.

“No, I can’t,” Wither replied. “He’s so excited to meet his new friends, he’ll be bouncing up that road without a care in the world.”

“I doubt he’ll bounce far with all those heavy books,” Tabitha said, and the door slammed closed.

I really did want to float to Still-Alive School, honest I did, but the thought of all those new faces—

Oh, and I’d forgotten my pencil case, and—anyway, my tummy told me it was time for an early lunch, so I hid the satchel in the stinging

nettles and floated over the house and in through the cellar window.

I had barely eaten half a sponge cake when in floated Charlie Vapor.

“Um,” I said, wiping icing from my mouth. “There was an earthquake, so the Still-Alive Headmaster sent us home, and the earthquake shook the shelf and the cake toppled into my mouth and—”

“Humphrey,” Charlie said as he toyed with his trilby, “you’re a big, cake-eating fibber. Wipe your mouth. I’m wisping you to Still-Alive School myself.”